Milan, 18 November 2024

Ever since 2016, when I wrote a post about Saint Radegund I’ve been meaning on and off – more off than on, I should say – to write a post about Saint Tecla, as part of my sub-category of posts on obscure saints whose names still dot the European landscape; in this particular case, a small road behind Milan’s Duomo is called after her. The last post in the series, from this summer, was about Sankt Ilgen. Two days ago, at the end of a hike which my wife and I did on Lake Como, I came across a church dedicated to Saint Tecla, in the village of Torno. It’s not a particularly interesting church. This is what the exterior looks like.

And this is a view of its interior.

Quite honestly, the view from the church’s door across Lake Como is more interesting.

Nevertheless, I took my bumping into this church as A Sign that I should finally get my finger out and write this post.

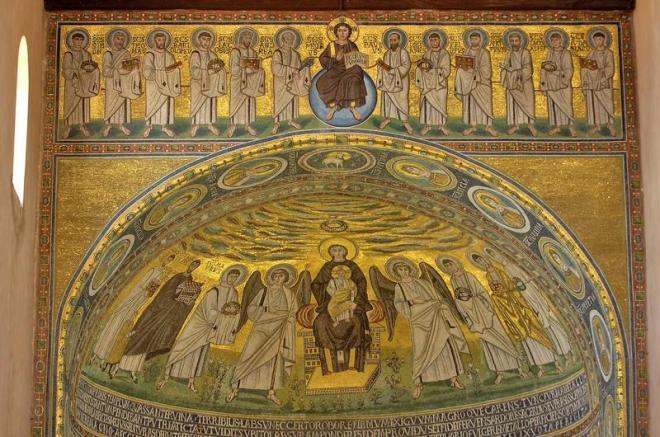

So who was this Saint Tecla? (and by the way, I prefer to use the Italian – and Spanish and Portuguese – spelling of her name rather than the English Thecla) Let me start by inserting a photo of a 6th Century mosaic portrait of her which graces the Basilica Eufrasiana in the town of Poreč in Istria, in Croatia.

For any of my readers who are interested in early Christian mosaics and have never visited the Basilica Eufrasiana, I suggest that you do so. I throw in a couple of photos of the mosaics there to whet their appetite.

Readers with good eyesight will see that the portrait of Saint Tecla is one of the portraits on the inside of the arch, to the right.

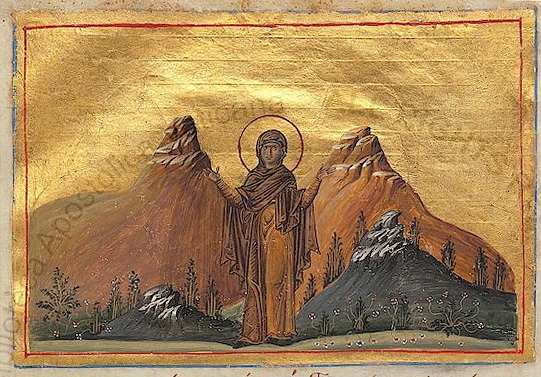

Given her great popularity in Christian Orthodox religions (probably much greater now than it is in Western Christian religions), I also throw in a photo of a depiction of her in a manuscript produced for the Eastern Roman Emperor Basil II in the 11th Century.

Of course, neither of these portraits is from life. And in fact, there is a good chance that Tecla never had a life – the Roman Catholic church quietly dropped her from its official Martyrology back in 1969, which normally occurred because there was a lack of historical evidence that the saint or martyr in question ever existed. But let us put this cavil aside, and see what her various hagiographers had to say about her.

Tecla was believed to have come from Iconium in the Roman province of Galatia (now Konya in the modern country of Türkiye). The story goes that when St. Paul passed through Iconium on his second missionary journey, Tecla was transfixed by his sermons. Here is the scene depicted in an altar carved in the 15th Century for a chapel in the cathedral of Saragossa in Spain, but which now resides in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cloisters. That’s Saint Tecla at the the window of her house. Note the man (I think) stroking his chin pensively down at the right; a nice touch.

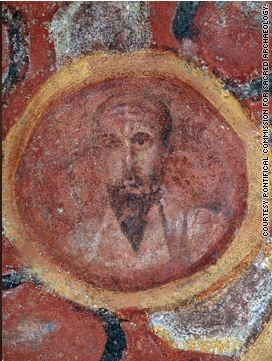

Unfortunately, Saint Paul seems to have lost his head. No worries, let me throw in a photo here of a fresco of St. Paul’s head, recently uncovered through the clever use of a laser-based technology, in a 4th Century catacomb named after St. Tecla, in Rome. This, I read, is the oldest extant solo portrait of the Apostle. I’m intrigued by the very pointy beard; I have never imagined Paul with that kind of beard.

Continuing on with Tecla’s story, she declared to her mother Theocleia and her fiancé Thamyris that she was abandoning her marriage plans and would join Paul. Both Theocleia and Thamyris were alarmed at this attempt at independence and decided to drag both Paul and Tecla before the city governor. Paul was merely sentenced to scourging and expulsion, but Tecla was to be burned at the stake. Turning again to that altar which once resided in Saragossa’s cathedral, we have the scene sculpted in alabaster. The sources say she was stripped naked, but that clearly didn’t play well with the sculptor and/or the donor.

Miraculously, a storm blew up, which doused the pyre. Personally, I would have put her back in gaol, built another pyre, and had a second go. But no, she was freed, whereupon she joined Paul, cut off her hair (I always find it interesting that hair is considered – by male authors? – such a sign of femininity, the cutting of which signifies renunciation of physical attraction), and followed him. And off they went to Antioch in Pisidia (nowadays called Yalvaç). There – even without her hair – she drew the lascivious attention of one Alexander, a nobleman of the city. He attempted to take her by force, but she fought him off, tearing off his cloak and knocking the coronet off his head in the process, much to the amusement of the townspeople. Seemingly, then, Alexander attempted this rape of Tecla, for that is what it seems to have been, in public, which is a little odd. Or maybe the writer of the story wanted to show the arrogance of power.

In any event, Alexander felt greatly injured in his aristocratic pride and had her dragged – yet again – in front of the city’s governor for assaulting a nobleman. This time, the governor condemned her to be thrown to the wild beasts (as an aside, I have to say that hagiographers of the early Christian martyrs all seem to have been working off the same playbook; martyrs were either burned at the stake, tortured in hideous ways, thrown into rivers with heavy weights around them, or thrown to wild beasts, or some combination of these). Interestingly, the women of Antioch rose up as one against the sentence, although it changed nothing (I think the hagiographers’ intention was to intimate that Tecla was a natural leader of women).

And so she was paraded through the streets of Antioch, stripped of her clothes (again), and thrust into the arena. The men in the crowds were baying for blood, the women were weeping for poor Tecla (taken by the spirit of the story, I have added this bit; as far as I know, none of the hagiographers said it, although they do make clear that the women in the crowd were rooting for Tecla). Miracle! Some of the wild animals (female) protected her from other (male) animals. A lioness was especially active in defending Tecla. We see the scene here in a 15th Century altar from the chapel of the Cathedral of Tarragona in Spain (in passing, I should note that Saint Tecla is the patron saint of Tarragona). In this case, the sculptor had no problems making Tecla at least half naked. Note all the animals lying meekly at her feet. I like, too, the crowd pressing in to see what’s happening.

At this point, the story gets somewhat muddled for me. Reading between the lines, and giving my fervid imagination free rein, I’m guessing that the organizers of this spectacle had thought up the idea of having a large vat in the arena full of ravenous seals. They must have thought they could throw the remains of Tecla, once she had been ripped to pieces by the wild beasts, into the vat (although I wonder if seals would eat human remains; but hey, what do I know?). But Tecla had other ideas. She had asked Paul to baptize her, although for some reason he had temporized. Standing in that arena, surrounded by wild – but currently meek – animals, she decided that before she died in that arena, she would baptize herself. Note once again her streak of independence: baptizing yourself?! impossible; only men can baptize people! Nevertheless, she threw herself into the vat. The altar in Tarragona’s cathedral gives us once again a vision of this scene.

I’m not sure what has happened to the arena and its crowds, we seem to have a more sylvan scene. I also get the impression that the sculptor had no idea what seals looked like, he seems to have come up with a bunch of eels. But le’s not niggle, because another miracle occurred! The vat was struck by lightning, which killed all the seals – but of course not Tecla.

All these miracles were too much for the governor. He ordered her clothed and released her to the rejoicing women of the city. She returned to Paul, “wearing a mantle that she had altered so as to make a man’s cloak” (an important phrase for future generations of some women, who looked to Tecla as an example of breaking the eternal glass ceiling for women). She went on to convert many people, including her mother, to Christianity, and then retired to a cave near Seleucia (today’s Silifke) where she lived for many decades. This is the exterior of the cave.

And this is a shot of its interior, which has been turned into a church.

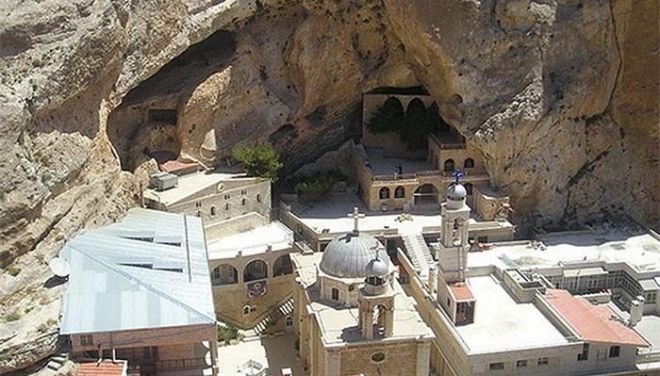

I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that there is a rival story that Tecla did indeed spend her last years in a cave, but in the small town of Maaloula in what was then the kingdom of the Nabateans, close allies of the Romans, and in what is now Syria. It seems a far more dramatic site, and has a Christian Orthodox church and nunnery built next to it.

The site, alas, has fallen prey to modern religious wars. ISIS fighters invaded Maaloula in 2013, going on a rampage against Christian people and buildings, destroying all religious sites in the town. 3,000 fled the city, leaving only Muslims and the nunnery’s forty nuns. Twelve of them were kidnapped, and after negotiations were release in 2014. The nuns were dispersed and were only able to come back to the town in 2018. Horrors continue to be committed in the name of religion …

There’s further bits and pieces to Tecla’s hagiography, but I’ll skip them. Given the story, it’s a bit of a mystery why Tecla was such a popular saint. As far as I can make out, her popularity rested on the fact that she offered early Christian women a strong example, equal to, not subordinate to, men. She offered a female equivalent to the – male – Apostles; she went around converting people just as much as Paul did. She threw off the bonds of what was a strongly patriarchal society – she broke off an engagement arranged by her family, in fact she turned her back altogether on marriage; she didn’t wait to be baptized by a man but just did it herself; she took to the road without a protecting male presence (although she seems to have had to pretend she was a man in order to do this). The Church Fathers, notably Ambrose of Milan, lauded her for her virginity – but I always suspect this approval of virginity by the Church, since it always seems to be tied to retiring from the world into a nunnery and being Wedded to Christ; the idea of being in this world on equal terms with men was anathema to the Church (and to society more generally). I suspect she could easily be the patron saint of this new B4 Movement coming out of South Korea.

Well, I’ll leave readers with a somewhat more modern take on Saint Tecla by El Greco, in his late 16th Century painting “The Virgin and Child with St. Martina and St. Tecla”. It was painted for the Oratory of St. Joseph in the city of Toledo, but is now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

We will, of course, immediately recognize Tecla because of the lioness which is protecting her. She also, rather oddly, is holding a martyr’s palm – oddly, because she actually was never martyred. One of the many strange things about Tecla.