Los Angeles, 29 November 2022

Our daughter is currently in the sleep-eat-repeat mode with her newborn. Since she is breast-feeding and the little one is somewhat dilatory at the breast, she spends a lot of her time sitting on the sofa either feeding him or having skin-time with him. Which in turn means that my wife and I have taken over a lot of the routine household tasks. One of these is doing the shopping at the local supermarket.

It was while we were on one of these shopping trips, traipsing up and down aisles trying to find things, that I came across these displays.

As sharp-eyed readers will see (especially if they blow up the photos), what we have here is a wide array of different brands of beef jerky (along with a couple of bags of turkey jerky and other dried meat products thrown in).

For those of my readers who are not familiar with jerky, it’s basically thin strips of lean meat which have been dried out to stop spoilage by bacteria. In the past, this drying was done by laying the meat out in the sun.

Alternatively, it could be smoked.

Nowadays, it is more often than not salted. It can be marinated beforehand in spices and – in my opinion, most unfortunately – sugar. The net result looks like this.

Contrary to what one might think, the meat is not that hard or tough; crumbly might be a better description. Depending on what marinades are used, it can be salty or – yech! – sweetish. If prepared and stored properly, jerky can remain edible for months.

My discovery of this display of jerkies got me all excited. Nowadays, it is marketed as a protein-rich snack. But in the old days, when the Europeans were moving west across North America it was a great way of carrying food around with you on your travels: light but rich in protein, long shelf-life, no need for refrigeration. I’m sure it was used by the pioneers as their carriages creaked slowly across the prairies.

But for me, it evokes more romantic visions of old-time cowboys out on the range driving cattle to the rail heads.

Or perhaps out in a posse hunting down Billy the Kid or some other outlaw.

I’m sure my boyhood cowboy hero Lucky Luke would have eaten jerky, although I don’t recall any of his stories showing this.

The drying of meat (and fish) as a way of preserving it has of course been used in many cultures all over the world, but jerky specifically has its roots in the Americas. The word itself hails from the Andes, coming from the language of the Quechua people.

When the Spaniards conquered the Incan Empire, they found the Quechua making a dried-meat product from the llamas and alpacas which they had domesticated. The Quechua called it (as transliterated into the Roman alphabet) ch’arki, which simply means “dried meat”.

The Spaniards must have been very impressed with this product because they adopted both the product as well as its name, hispanicised to charqui, and spread its use throughout their American dominions. Not surprisingly, though, the source of meat changed along the way, with beef coming to predominate. So did the methods of preparation and drying. The Quechua dried pieces of meat with the bone still in place and they relied on the particular climate of the high Andes for the drying, with the meat slow-cooking in the hot sun during the day and freezing during the night. The Spaniards instead ended up cutting the meat into small thin strips and smoke-drying them.

I have to assume that when, in their migrations through the Americas, other Europeans collided with the Spaniards, they adopted this practice of preparing and eating dried beef; they also adopted the name, although the English-speaking among them eventually anglicized it to jerky. The Romantic-In-Me would like to think that American cowboys picked up the jerky habit from Mexican vaqueros somewhere out in the Far West.

But there is probably a more mundane explanation. Take, for instance, John Smith, who established the first successful colony in Virginia, at Jamestown, in 1612 (and who Disney studios had looking like this in the animated film Pocahontas

but who in reality looked more like this).

Smith had obviously heard of jerky. He had this to say about the culinary habits of the local Native American tribes he met living around the new colony: “Their fish and flesh … after the Spanish fashion, putting it on a spit, they turne first the one side, then the other, til it be as drie as their ierkin beefe in the west Indies, that they may keepe it a month or more without putrifying.” Which suggests that the name “jerky” may have come to North America via the Caribbean island colonies and a good deal earlier than the cowboys.

John Smith’s comment also tells us that the habit of drying fish and meat to preserve it was prevalent throughout the Americas – which is not really surprising; as I said, many cultures the world over have discovered this method for preserving fish and meat. Having no domesticated animals (apart from dogs), the First Nations of North America sourced their meat from the wild animals that roamed free around them: bison, deer, elk, moose, but also sometimes duck. Which brings me in a rather roundabout way to another foodstuff that makes me dream, pemmican.

For those of my readers who may not be familiar with this foodstuff, it is made by grinding jerky to a crumble and then mixing it with tallow (rendered animal fat) and sometimes with locally available dried berries. Like jerky, it can last a long time. This is what pemmican looks like.

The word itself is derived from the Cree word pimîhkân – other First Nation tribes had different names for it, but I suppose the Europeans only started using it when they entered into contact with the Cree people.

Why, readers may ask, does pemmican make me dream? Here, I have to explain that there was a time in my life, in my early teens, when my parents lived in Winnipeg, capital of the Canadian province of Manitoba. Winnipeg became an important link in the beaver fur trade routes which linked the north-west of Canada with both Montreal and Hudson Bay. A book I read when I was a sober adult, titled “A Green History of the World”, informed me that the trade itself was a catastrophe, leading to collapse after collapse of local beaver populations as they were hunted out of existence in one river system after another. But when I was a young teen, it wasn’t the poor little furry animals that interested me, it was the voyageurs. These were the men (and only men) who held the fur trade together. It was they who paddled the big canoes which in the Spring carried goods out west to trade for the beaver furs and in the Fall carried the furs back east.

To the Young Me, the lives of these voyageurs seemed impossibly romantic: paddling through the vast wilderness that was then Canada

sleeping by the fire under the stars

meeting people of the First Nations when they were still – more or less – living their original lives …

I had one, tiny taste of this life when I was 14 going 15, paddling a canoe for a couple of weeks along the Rainy River and across Lake of the Woods, camping at night on the shore of the river and on islands in the middle of the lake

and one day meeting a very old man on one island who thrillingly remembered as a child hiding from the local First Nations tribes who had gone on the warpath.

Of course, the voyageurs’ life was considerably harder than I ever imagined it as a boy. For instance, coming back to pemmican, they didn’t have space in their canoes to carry their own food, nor did they have time to forage for it. They were expected to work 14 hours a day, paddling at 50 strokes a minute or carrying the canoes and their load over sometimes miles-long portages, from May to October. So they had to be supplied with food along the way. In the region around Winnipeg that meant being supplied with pemmican.

A whole industry sprang up to supply the large quantities of pemmican needed by the voyageurs. It was run by the Métis, another fascinating group of people. As the Frenchmen (mostly, if not all, men) pushed out into the Canadian West, many married, more or less formally, First Nations women from the local tribes. The primary purpose of these marriages was to cement trading relations with local tribes; it was also a way of creating the necessary interpreters. The children of these marriages were the Métis (which is French for people of mixed heritage). They in turn intermarried, or married First Nations people, and over time, created what were essentially new tribes. Although the Métis retained some European customs, the most important of which being the speaking of French, for the most part they adopted the customs of the First Nations.

There were especially large groupings of Métis around what was to become Winnipeg. One of the bigger groupings lived in St. Boniface on the Red River.

This has now become one of the quarters of Winnipeg, and is where my parents used to live. At that time (we are talking the late 1960s), most of the population of St. Boniface was still Francophone and I suspect that many were descendants of the Métis, although they would not have publicized the fact. Being Métis was rather looked down on at the time.

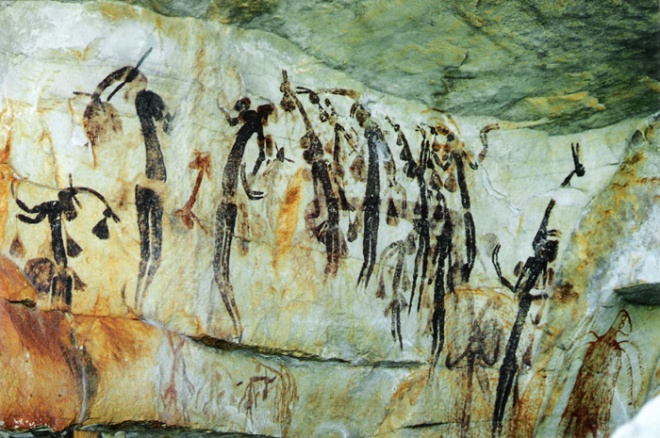

One of the customs which the Métis adopted from the First Nations was the making and eating of pemmican, hunting the numerous bison which then still roamed the central plains of North America for both the meat and the tallow they required. But the demand from the fur trade business upped the ante, and the Métis started producing pemmican on a quasi-industrial scale. Twice yearly, large hunting groups left the Winnipeg area and moved south and west looking for the bison herds. Here we have a series of paintings, watercolours, and lithographs showing the various phases of these bison hunts.

The Métis encamped out on the plains.

The hunts.

Drying the bison meat and creating the tallow, preparatory to mixing them to make pemmican.

It all seemed glorious to me when I was a boy – a sort of souped-up, months-long Scout camp – but as a sober adult I learned of the very dark side of these twice-yearly hunting expeditions. Huge numbers of bison were killed during these hunts, especially females, which were the preferred target; this was a significant factor in the near-extinction of the bison in North America. Luckily, they have survived, although in much diminished numbers. One summer in Winnipeg, my father took us to a park where bison ranged free; we were able to get quite close – magnificent animals.

On that same trip, we spied a beaver dam somewhat like this one in the photo below through the trees and decided to go and have a peek.

But we were driven back by the swarms of voracious mosquitoes which, literally smelling blood, rose up from the ground as one and closed in on us. The voyageurs were also much troubled by mosquitoes and black flies during the few hours of sleep allowed to them; they used smudge fires to keep them away. As a result, many suffered from respiratory problems – another side to their not-so romantic lives.

My father also used to take us for rides down towards the American border, where the Métis had once travelled for their bison hunts, trekking across prairies which – as the paintings above intimate – had stretched to the horizon. But they’ve nearly all disappeared too; a few shreds remain in some national parks.

What we saw was wheat stretching to the horizon.

Ah, memories, memories … I’ve told my wife that one day I’ll take her to Winnipeg. We can visit St. Boniface and talk French. And drive through the endless waves of wheat towards Saskatchewan. Perhaps go north to Lake Winnipeg, so big you can’t see the other side of it from the shore. And camp out in a provincial park, under the stars.