Milan, 27 June 2020

This post was going to be about the oleander, but as often happens when I surf the web I disappeared down some fascinating rabbit holes along the way. So while I will discuss the oleander I will also throw in a couple of disparate facts linked more or less tenuously to the oleander.

First the oleander. The walks which my wife and I have been taking recently on the Ligurian coast have led us past many an example of this fine plant, whose showy red and pink flowers have lit up our way, especially when we have been traversing urban sections of our walks.

As usual, after quietly enjoying at this display from Nature, I looked to the plant’s history, to see where it had originally come from (not believing for a minute that it could be native to Liguria). What I found was, I suppose, a testimony to its enduring attraction to humans as well as to its toughness and endurance: enduring attraction to humans because it’s been domesticated for such a long time that no-one can make out its original home – South to South-West Asia seems to the best guess; toughness and endurance because even when taken out of its native habitat it has survived and thrived and created new homes for itself – here is a picture of oleander which has gone native in northern Israel, growing along the side of streams.

It has gone similarly native in many places, from Portugal and Morocco in the west to Yunnan in China in the east.

Its toughness and endurance has made it a popular plant to use in unforgiving environments, like the median strips of highways: you can’t get much tougher than that – poor, stony soil, little water, fumes from the passing cars, collection point for all the rubbish that people throw out of their cars, or that drop off their cars. As a bonus, it almost makes highways look pretty.

One of the first things that struck me when I went to Sicily was the oleander bushes along the highways there, the flowers turning what was really a very sterile environment into a pleasure to look at as the car whizzed down the highway.

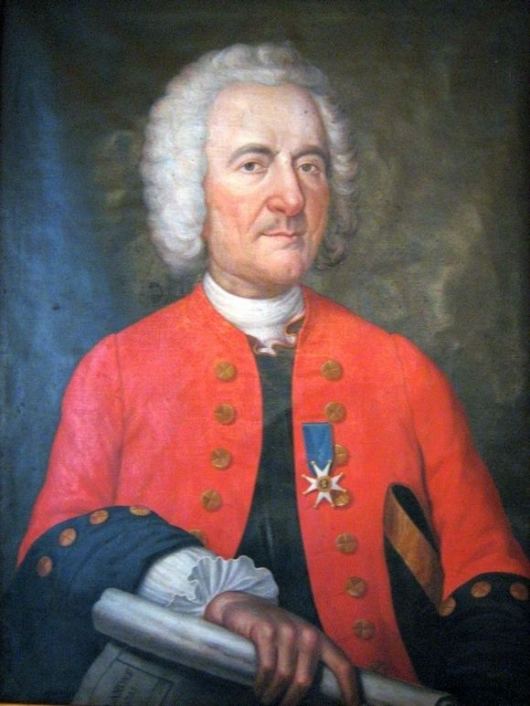

The only other thing to note about oleander is its poisonous effects on humans and other animals. Every part of the plant is poisonous: in a word, beautiful but deadly. A couple of books have had as plot devices the murder of someone with oleander. For me, the best is Dragonwyck, not so much for the book as for the 1946 film made from the book. It has Vincent Price, a slimy smoothie if there ever was one, who does in his wife with oleander. We have him here staring broodingly at the fatal oleander plant.

Actually, oleander’s deadliness has been exaggerated. It’s not really that bad. Very few people have certifiably died from ingesting oleander. The worst that normally happens is that you feel horribly sick, you vomit, you get diarrhea … I’m sure I don’t have to spell it out, readers get the picture.

And that’s it, really, for the oleander. Now I can turn to the rabbit holes I fell down!

The first is related to the plant’s effects on humans. But I must start with a little bit of context. I want to take my readers to Delphi, in Greece.

Now the place is just a mass of romantic ruins, but in its heyday, from about 600 BCE to about 200 CE, it was really famous in the Ancient World, a place to go to if you wanted divine advice about something important to you: should our city go to war with our neighbour? should we start a new colony? or, on a more personal level, should I marry her? The temple there was dedicated to the god Apollo, and one of the temple’s priestesses, the Pythia, would answer your question. After offering a splendid goat for sacrifice and paying a suitable tribute (there’s no such thing as a free lunch), supplicants would be led down into the inner sanctum of the temple, this dark small room, where they would find the Pythia sitting on a tripod and flanked by a couple of priests. The tripod was placed across a cleft in the floor through which vapours or fumes would be rising and enveloping the Pythia. She would be holding a branch of laurel in one hand (the laurel was sacred to Apollo) and a small basin of clear water from a nearby sacred stream in the other. Rustling the laurel branch and gazing into the basin of water, she would answer your question. Here is the scene depicted on the bottom of an ancient Greek drinking cup, the supplicant to the right, the Pythia to the left.

Now, this was not like having a pleasant conversation with someone. The Pythia would be pretty agitated: “her hair stood on end, her complexion changed, her heart beat hard, her bosom swelled, and her voice became seemingly more than human”. Here is a much more satisfyingly dramatic rendering, painted by a certain John Collier in 1891, of what the Pythia might have looked like.

The whole experience must have been quite unnerving and overpowering for the supplicants. On top of it, the answer they got was often quite cryptic, leaving the supplicants scratching their heads trying to understand the true meaning of what Apollo had told them through the Pythia.

Why am I recounting all this? Because there has been considerable discussion about how the Pythia got herself all worked up. What was she eating, drinking, or smoking to get herself into that state? Some of the ancient sources say that the Pythia was chewing laurel leaves. But as we all know – bay leaves, which are actually laurel leaves, being used in cooking – laurel leaves don’t have any effect on someone who eats them. Which is where oleander comes in. The Greeks were rather slipshod in their use of the name “laurel”, using it to denote several plants including the oleander (the leaves of the oleander and the laurel do look quite similar). So one clever chap has suggested that the Pythia was actually chewing oleander leaves, which could indeed give you all the symptoms the Pythias exhibited.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the vapours and fumes emanating from the cleft under the Pythia’s seat (and which are very evident in the painting by John Collier). Some have argued that it could have been these that (also) set the Pythia off. Given that Delphi sits on two geological faults which cross each other, it is thought in certain circles that the cleft which the Pythia sat astride was a natural opening into the bowels of the Earth. There has therefore been much discussion about what naturally formed fumes and vapors could have been seeping out from the Earth’s interior and been having this effect on the Pythia – ethylene? benzene? something else? – but it’s all been quite inconclusive. The above-mentioned clever chap suggests what seems to me a much simpler solution, that maybe under the room where the Pythia sat was another room, connected to the former through the cleft, and in which a priest was burning oleander leaves. By inhaling these fumes the Pythia was adding to the effects from chewing the leaves.

That’s one interesting rabbit hole connected to the oleander.

The other involves Hiroshima. As I would hope everyone knows, the first atom bomb ever dropped came down on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. Here is a picture of the dreaded mushroom cloud which formed over the city.

The city was totally devastated. Here are a few pictures of what the city looked like in the days and months after the dropping of the bomb.

The city’s botanical gardens were not spared. So bad was the destruction that the garden’s directors thought that nothing would grow there again for decades. Yet lo and behold, the year after the bomb was dropped the oleanders in the gardens grew out from their blasted roots and flowered! The oleanders became a symbol of hope for Hiroshima’s citizens, convincing them that the city could be reborn even after this terrible catastrophe – as indeed it has. Ever since, the oleander has been the city’s official flower.

I’ve become a bit of a cynic in my old age, but this little story does warm the cockles of my heart.