Milan, 2 May 2022

Whenever my wife and I complete a hike, we like to give ourselves a little treat. In my last post, I described the rum baba I will have after hiking in Liguria, coming off the Monte di Portofino and rolling into Santa Margherita. But the more common treat we’ll give ourselves for completing a hike in Italy is an ice cream. I mean, after a long hike in Italy, when you’re tired and hot, is there any better treat you could give yourself than a gelato?

Given the enjoyment we get from consuming ice creams (my wife especially), I’ve been meaning to dig deeper into this delicious foodstuff for some time now, but have never quite got around to it. My writing of the previous post on the rum baba finally turned thought into action.

Let me immediately be completely up front. For decades now, I have been eating ice cream but I have never, ever made the stuff. The making of ice cream has been a completely closed book for me. Until now.

As usual, I began to read; not just on the making of ice cream but also – given my natural proclivities – on its history. And the more I read – or rather, the more rabbit holes I fell down – the more I realized that the story of ice cream was intimately linked to the stories of the sorbet and the granita.

Not only that, but the stories of all three were intimately linked to the story of the trade in ice and snow. Since it was the latter that allowed the creation of the former, let me start with this.

We are all now so used to artificial refrigeration that we don’t give a second thought to going over to that white, quietly humming box in our kitchens on a devilishly hot day and pulling out cold food and drinks.

But in the history of mankind, that’s a really recent phenomenon – artificial refrigeration has only been around for some 120 years. Before that, on that hot day you could only sweat and dream of that cool, cool beer, and if you had fresh produce you made sure to eat it as quickly as possible before it spoilt. Unless, that is, you were a king or emperor or other potentate, or generally were incredibly rich; one of the 1%, or more likely the 0.001%.

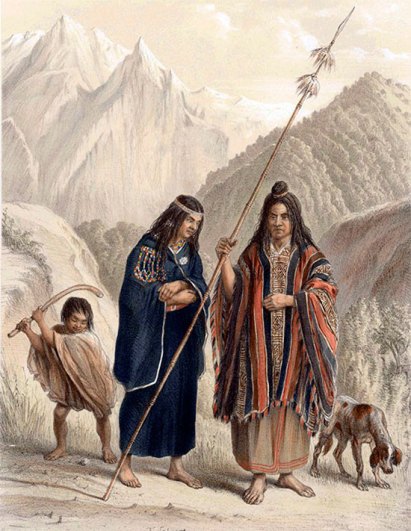

In this case, you had another option, that of paying people to climb high mountains where snow lay even in summer, to collect that snow and bring it back to your palace or other rich man’s pad.

Once there, you would store it in an ice house. Your servants (or probably your slaves) would pack the snow in, insulating it as well as possible (straw seems to have been a popular insulating material; sawdust is also mentioned). Here is a type of ice house used in Persia.

After which, it could be doled out during the hot months to keep food fresh or to make cold desserts with which to turn your guests green with envy when you invited them around for a banquet. I suppose it was the ancient equivalent of a Russian oligarch inviting guests for a spin in his super yacht.

This practice has a long history. There are cuneiform tablets which show that snow was already being carried down to the plains of Mesopotamia in about 1750 B.C.E. The Persians were carrying snow down from the Taurus mountains in about 400 B.C.E. The Greeks did it, as did the Romans, bringing snow down from Vesuvius and Etna, as well as from the Apennines. Snow was carried down from the mountains of Lebanon to Damascus and Baghdad. The Mughal emperors had snow carried down from the Himalayas to Delhi. Granada and Seville had corporations which were tasked with carrying snow down from the Sierra Nevada to these cities. The Spaniards brought the practice to the New World, both to their Andean colonies as well as to Mexico.

In regions where climates were sufficiently cold in the winter for good ice formation on water bodies, a different strategy could be adopted: the ice was harvested during the winter and stored in ice houses for use during the summer. The Chinese were doing this by the time of the Tang Dynasty, if not before. Kings and aristocrats from Europe were doing it by the 16th Century, using ponds or lakes on their large estates to create the necessary ice, which they would then store in their ice houses. My wife and I recently came across this on one of our hikes around Lake Como. We happened to visit one of the old villas on the lake, Villa del Balbianello.

Tucked away in the corner of the grounds, on the cold side of the hill, was this ice house (in which, I should note in passing, the last owner had himself buried).

Rich colonialists in New England and the Canadian provinces copied the practice. But the democratic (and capitalist) spirit of the colonies was too strong. By 1800, businessmen in New England democratized the practice, harvesting ice on a large enough scale to make it affordable for modest households, who could use it in primitive refrigerators.

The ice was delivered to one’s doorstep by ice vendors.

These New England “ice entrepreneurs” even began to export their ice, eventually exporting it as far as Australia! Norway learnt from the Americans and got into the act on a big scale, exporting ice to many countries in Europe. Other European countries got involved in this international trade on a more modest scale: Switzerland exported ice to France, ice harvested in the mountains along what is now the Italian-Slovenian border were exported through the port of Trieste to countries further south in the Mediterranean, …

This flourishing ice business came to a crashing halt when artificial refrigeration came along in the early 1900s. The take-over by artificial refrigeration came in stages. Until quite recently, ice was still being delivered to households (I remember my parents receiving their deliveries of ice in the 1960s in West Africa), but now that ice was being made in a centralized refrigeration plant and not in a lake. And then even the local trade in ice disappeared as just about every household eventually owned their own refrigerator.

Coming back now to the Holy Trinity of ice cream, sorbet, and granita, as I said earlier one of the things all those rich Mesopotamians, Chinese, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Indians and other moneyed folk could do with the ice they had had collected was to have their cooks make cold desserts. What exactly these cold desserts were composed of is a bit of a mystery, but we can guess that the ice, no doubt crushed in a mortar, was mixed with honey or various fruit-based syrups and served to guests, perhaps sprinkled with petals, seeds and other such niceties. Something like this – without all the niceties, though – was quite a common summer street food in Italy in the 19th and early 20th centuries, made affordable by a plentiful supply of cheap ice – indeed, you can still find it to this day in one or two places in Rome, under the name of grattachecca.

Basically, ice is grated from an ice block and put into a glass, onto which are then poured various types of syrups – black cherry, tamarind, mint, orgeat, coco, lemon, you name it …. Simple, cheap, and cooling on a hot summer’s day. If any of my readers are in Rome on a hot summer’s day and want to try a grattachecca, this is one of the places you can still get it.

I’ve never had a grattachecca, but I can imagine one drawback with it. When it’s still cold you take a mouthful of the mixture and end up swallowing the now-watery syrup and then sucking on tasteless pieces of ice. And when it’s warmed up all you’re having is a cold drink.

Then, in the 16th Century in Europe, came a revolutionary discovery. Someone, somewhere discovered that if you put salt on ice you can actually drop the temperature to below 0°C. Anyone living in a country with cold winters is familiar with this phenomenon. It’s behind the use of salt on roads to melt black ice. I won’t go into the science behind the phenomenon, fascinating though it is. I’ll just say that you can drop the temperature to as low as -20°C in this way! I can’t stop myself throwing in a so-called phase diagram for salt solutions. They’re kind of neat, and any of my readers who have studied some science at some point in their lives can have fun looking at it. Other readers can skip it.

It may not be immediately obvious to readers why this was important to our particular story. But what it meant was that cooks finally had a way of freezing things rather than only being able to cool them using ice from the ice house. We’re so used to having artificial refrigeration at our fingertips that we can have difficulties understanding what a revolution this was.

As far as our story is concerned, this was the key to making granita, sorbet, and ice cream. That snow brought down from the mountains or the ice harvested from a nearby lake were now no longer an intimate part of the dessert; instead, mixed with salt, they became merely an operational material in the making of that dessert. Center place was now given to various sweet concoctions which cooks came up with and which they then froze.

Or actually, as far as our Holy Trinity is concerned, partially froze. Because if granite, sorbets, and ice creams were truly frozen, they would be hard as rock and completely inedible. They needed to be cold but soft enough to be scooped up with a spoon – or bitten or licked off, as we see these French ladies, post French Revolution, doing with gusto.

Here, sugar is key. Just as salty solutions of water freeze at lower temperatures than pure water so do sugary solutions. In effect, what happens as you cool sugary solutions below 0°C is that the water molecules freeze, creating crystals of ice, while the sugar molecules do not. The result of this is that as more and more water molecules are pulled out of the sugary solution to form crystals, so the remaining sugary solution gets more and more concentrated. In addition, the sugar molecules get in the way of the crystallizing water molecules and impede them from ever creating big ice crystals. The net result of this is a whole lot of small to tiny ice crystals scattered throughout a very sugary syrup. It is primarily this that gives granite, sorbets, and ice creams their cold but semi-solid consistency (primarily, but not wholly; another ingredient, which we’ll get to in a minute, is present in sorbets and ice creams, and is very important in ensuring that semi-solid consistency).

But what were the sugary solutions that cooks began to freeze? And to answer this, we have to look at the history of a sweet drink called sharbat. The roots of this drink are in Persia, where it continues to be drunk to this day.

Originally, it was simply sugarcane juice (sugarcane had been brought to the Persian lands from India in the 8th Century). But to this base Persians added various things: syrups, spices, herbs, nuts, flower petals, and what have you. And, if you were a very rich Persian, it was cooled with that snow and ice which you had paid handsomely to have brought down from the high mountains. The Turks adopted the drink, calling it şerbet. And then the Venetians, and possibly other Italian traders who traded with the Ottoman Empire, brought the drink back to Italy, calling it sorbetto. The Turks helpfully created ready-mixed, transportable şerbet bases to which water could be added; these came in the form of syrups, pastes, tablets, and even powders. Since cane sugar was not yet readily available in Europe, I’m guessing that it was in one of these forms that şerbet first entered Italy and then other European countries. Certainly in the 17th Century the UK was importing “sherbet powders” from the Ottoman Empire (and no doubt these powders are the ancestors of that revolting powder now sold in the UK as “sherbet”, which tastes horribly sugary and fizzes in your mouth when you eat it).

This sugary drink was perfect for our new freezing process. Without wanting to fly any flag too ostentatiously, I think it was the Italians who first applied the process to the sorbetto drink and basically turned this drink into a semi-solid dessert. Recognizing the origin, the granita was initially called the sorbetto granito while the sorbet was called the sorbetto gelato. With time, the former simply became known as the granita and the latter as the sorbetto (while the gelato bit got assigned to the ice cream).

But what actually is the difference between the granita and the sorbet? Two things. The first is the size of the ice crystals. In the granita, they tend to be larger than in the sorbet – but not too large! Otherwise, you would end up with something like the grattachecca. It’s the larger crystals that give granita its granulous feel in the mouth (hence the name). One can fix ice crystal size by playing around with the amount of sugar (the less sugar, the larger the crystals) and by the amount of stirring one does as the solution is freezing (the more stirring, the smaller the crystals). You have here a strawberry granita. Notice the bun in the background; in Sicily especially, where the granita is very popular, it is common to eat one’s granita with a bun.

The sorbet, on the other hand, has tiny crystals. And it has a secret ingredient: air. Someone, somewhere had the idea of constantly churning their sorbetto as it was freezing, rather than churning it from time to time as is the case with the granita. Not only did this constant churning stop the ice crystals from growing, it also introduced a lot of air into the mix. The tiny ice crystals made for a much smoother sensation in the mouth, while the air led to a softer product (and to higher profit margins since the air was free and it puffed up the volume). Staying with strawberries, here is a strawberry sorbet.

Another someone, somewhere invented a machine specifically for making sorbets, known of course as a sorbettiera in Italian and a sorbetière in French. Here’s a model from the late 1800s.

Which brings us to ice cream. Yet another someone, somewhere had the bright idea of adding cream and egg yolks to the sorbet mix. This complicates the science even more, because with the cream you have added fats to the mix and as we know fat and water don’t mix, which is where the egg yolks come in. They act as an emulsifier, which is a fancy term for something that gets molecules unwilling to mix to do so. I suppose the idea was to make sorbets “creamier”, or maybe someone was playing around in a kitchen, decided to see what would happen if you added cream and egg yolks and hey presto! ice cream was born.

Otherwise, ice cream was made like sorbet: constant churning and dragging in of air. Voilà! Or maybe I should say Ecco! because I’m almost certain Italians invented ice cream. Staying on theme, here is a strawberry ice cream.

As I said earlier, since air is free and puffs up the volume of the product it’s very much in the interests of manufacturers of low quality ice cream to get as much air into their product as possible. Which leads to that disgusting ice cream which comes out of a machine like toothpaste and looks like this.

This revolting product is my first memory of ice cream, bought from a truck like this one.

They nearly put me off ice cream for life. It was only when I came to Italy that I began to enjoy ice cream.

Now as I say, I’m almost certain that it was the Italians who invented both sorbet and ice cream. But it was the French who really put them on the map – the must things to serve your guests. And in those days at least, as far as tastes were concerned, where the French went the others followed.

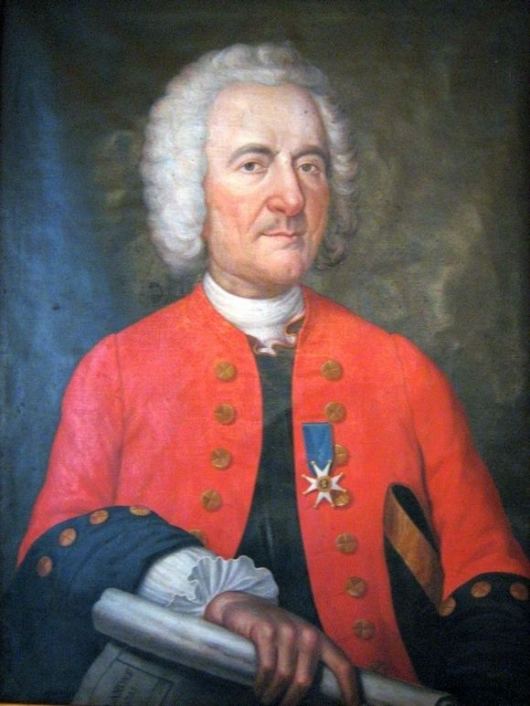

It was a café – another novelty of the age – that made sorbet and ice cream all the rage. The Café Procope opened its doors in 1686, in the reign of Louis XIV. It was established by an Italian, a Sicilian to be precise, by the name of Francesco Procopio Cutò.

Cutò emigrated to Paris at the age of 19. After working for a couple of years as a garçon in someone else’s café, he managed to scrape enough money together to buy the-then oldest café in Paris at the tender age of 21 and had enough hubris to give it his name. It was a fantastic success; all the chattering classes of the time came running to his café, and devoured its famous sorbets and ice creams. As far as sorbets were concerned, the café offered 80 different types! Some of the more popular tastes were mint, clove, pistachio, daffodil, bergamot, and grape. I’ve not been able to discover how many types of ice cream the café offered but presumably the listing was just as long.

From the Café Procope the sorbet and ice cream entered the kitchens of the Parisian moneyed classes, and from there they entered the kitchens of the European moneyed classes more generally: all the rich Europeans wanted to ape the French rich folk. And from there, they spread to the kitchens of more modest middle class households: everyone wanted to ape their social superiors. And from there, the industrial revolution turned the ice cream especially (not so much the sorbet) into a cheap and not terribly good product, to be consumed by the masses on their day out at the seaside.

So it is with many, many products. Luckily, though, the Italians still make high-quality but affordable ice creams, which my wife and I can enjoy after a long, hot and tiring hike. Thank God for that!