Vienna, 14 October 2023

All along the arc of the Alps, the farmers must be bringing their cattle down from the high Alpine pastures where they’ve been grazing all summer. Or maybe they’ve been down a few weeks already. A couple of years ago, in late September, my wife and I went hiking up one of the side valleys of the Inn valley, near Innsbruck, and we were lucky enough to catch the ceremony of the cows being brought down from their high pastures. And it really is a ceremony. The cows are decorated with floral wreaths, while the herders wear traditional dress. I only managed to take one rather poor photo of a cow with her floral wreath.

But others have posted much nicer photos online.

This ceremony is of course meant to signal that bringing the cows home is a joyful occasion, but this summer my wife and I came across a story which shows that it cannot always have been so joyful. We were starting a hike up into the Totes Gebirge (the Dead Mountains; strange name) from the shores of Altaussee lake. My wife later took this very Japanese-looking photo of the lake.

As we walked along the lakeshore, there came a point where the path narrowed dramatically, with a steep drop into the lake. And there, on the side of the path, we passed this memorial nailed to a tree.

The picture gives us a pretty clear idea of what happened, but the German text removes any doubt. It says:

On 17 October 1777, Anna Kain, aged 32, died here. During the cattle drive she was pushed by a cow into the lake and drowned. Lord, grant her eternal rest and a joyful resurrection. Amen

At the lake’s end, we swung left onto a trail that took us 1,000 metres up to the high pastures of the Totes Gebirge. As we crossed them, making for the mountain hut we would be staying the night at, we came across cows placidly munching away.

Judging by the old cowpats on the trail up, these cows had used the same trail we used to get to the high pastures in the early Summer, and will be going down the same way – like those cows back in 1777 – round about now, if they haven’t already done so. Given the narrowness and roughness of the path, it’s a miracle that more Anna Kains – and cows – didn’t fall off the path to a sure death. Perhaps they did but got no memorial.

Taking cows to and from the Alp’s high pastures seems to be a very old tradition, maybe 6,000 years old. It has been a key element in the economies of the Alpine valleys, so key that I can hazard to state that Switzerland exists because of it. As readers can imagine, locals living in Alpine valleys saw the surrounding high pastures as theirs and didn’t take too kindly to outsiders trying to cut in. In the early 1300s, a long-simmering feud between the people of Schwyz and Eisiedeln Abbey over grazing rights erupted into active fighting. Settlers from Schwyz had moved into unused parts of territories claimed by the Abbey, where they established farms and pastures. The abbot complained to the bishop of Constance, who excommunicated Schwyz. In retaliation, a band of Schwyz men raided the abbey, plundered it, desecrated the abbey church, and took several monks hostage. The abbot managed to escape and alerted the bishop, who extended the excommunication to Uri and Unterwalden (I suppose they had loudly applauded the exploits of their Schwyz neighbours, or maybe even taken part). It so happened that the abbey was under the formal protection of the Hapsburgs, so Leopold I, Duke of Austria, decided to show who was the boss. In 1315, he sent in an army to teach these Swiss peasants a lesson. But the clever men of Schwyz, supported by their allies from Uri and Unterwalden, ambushed the Austrian army near the shores of Lake Ägeri in Schwyz. After a brief close-quarters battle, the army was routed, with numerous slain or drowned. This illustration from the Tschachtlanchronik of 1470 shows the Austrians being skewered on land and drowning in the lake. Amen

This victory led to the consolidation the so-called League of the Three Forest Cantons, which formed the core of the Old Swiss Confederacy, which in turn eventually became the Swiss Confederation that we know today.

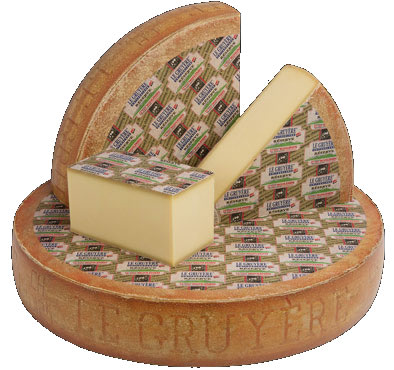

As I said, grazing cattle on the high pastures is an old, old tradition. So for millennia now we have had cattle eating fresh Alpine grass all summer long and making what German-speakers call heumilch, or haymilk. Milk aficionados say haymilk tastes different from normal, valley bottom milk, where the cows also eat fermented feed. I bow to the experts, never having drunk haymilk in my life (although maybe I should check the local supermarket shelves; it wouldn’t surprise me if the Austrians offer heumilch as a local delicacy). But in the days before refrigeration, the milk which the cows produced all summer long in the high pastures couldn’t just be drunk; it had to be turned into a more durable product. Thus we have the creation of that glorious, glorious category of cheeses, the Alpine cheeses. I’m sure we’ve all heard of some of the more famous Swiss entries to the category: Emmental, Gruyère, Raclette, Appenzeller. But every country with Alpine territory has their champion Alpine cheeses: Beaufort and Comté in France, the various Almkäse, Alpkäse and Bergkäse in Austria and Bavaria, Fontina in Italy. I use a wheel of Gruyère as a stand-in for all these wonderful Alpine cheeses.

I also throw in a cut of Emmental, because of those holes so beloved by children.

In the old days, those holes, or “eyes” in the technical jargon, were considered unfortunate imperfections in the cheesemaking process. But then some Swiss PR whiz kid turned the imperfections into a Unique Selling Point and fortunes were made in the Emmen valley and beyond. Several other Alpine cheeses have eyes, although not as big as those in the photo above. They are caused by the presence during the cheesemaking process of a bacterium which produces carbon dioxide – the holes are actually bubbles of carbon dioxide.

The presence of this bacterium is due to a particularity in the process for making Alpine cheeses. Unlike most cheeses, where salt is liberally used during the cheesemaking process, the herders up in the high pastures used very little if any salt, simply because it was heavy and thus a pain in the ass to haul up to the high pastures (having carried moderately heavy backpacks up mountains, I can sympathise). Instead, timber was plentiful up there.

So the herders chopped trees down, made fires, and cooked the curds in copper kettles. Even though things are considerably easier now, low salt and cooking on copper is still an important part of the Standard Operating Procedure for making these cheeses, and it is the low salt levels (and low acidity levels) that allow the bubble-making bacterium to flourish.

Once the herders had made those large wheels of cheese, they had to also bring them down to the valley bottom. I wonder how they did that? When they were bringing the cows down, did they roll them down like those crazy people in Gloucestershire who take part in the annual Cooper’s Hill Cheese Roll?

You can see these mad people charging down a hill after a cheese wheel.

As we can see, the hill is pretty steep and people seem to just tumble down.

And somehow, someone wins.

I can’t believe herders would have rolled the wheels, even in a more temperate way. It would have ruined them. They were valuable products (indeed, a number of those pesky abbeys had their peasants pay their annual tribute in cheese wheels). I have to guess that the herders loaded them up on the cows when they brought them down, or maybe they had a team of mules for this. Or maybe there were people who spent the whole summer going up to the high pastures and then staggering back down with wheels of cheese on their backs.

Well, I can think of no better way for me and my wife to salute those Alpine cows and the haymilk they produce than for us to break our boring diet and get ourselves a nice slice of Alpkäse or Bergkäse (or both? in for a penny, in for a pound!) and eat it (or them) one of these evenings, with a big chunk of bread and a nice glass of wine. And why not throw in some nuts while we’re at it? In for a penny etc.