Milan, 28 February 2025

It was freezing cold in Vienna this last month we were there, far too cold for my wife and I to go hiking. So we spent our spare time visiting Vienna’s nice, warm museums. One museum we visited was the Paintings Gallery of the Academy of Fine Arts; I don’t think we’ve been back to it since a visit we made shortly after we arrived here, back in 1998. As the name indicates, we are actually dealing with an arts school, but it has quite a worthy collection of paintings donated to it by various aristocrats over the centuries. It has a particularly good collection of paintings by Lucas Cranach the Elder, and it was one of these that caught my attention, St. Valentine and a Kneeling Donor, painted in 1502-1503.

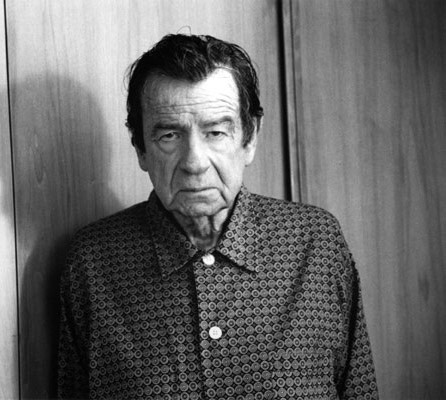

What a magnificent face St. Valentine has! Not a handsome face at all, but it still had me gazing at it in fascination. A face full of character! If I were to meet this person in real life, my staring at him would probably provoke him into demanding what the hell I was looking at and to scarper before he took a swing at me. His face reminds me of the actor Walter Matthau at his most scowling.

From today’s perspective, what with the saint’s feast day of 14 February being irremediably lodged in our collective memories as the day of lovers, I think many people would be surprised by Cranach’s choice of model. They might have someone more sucrose in mind, like this painting in the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Rome.

But that is to forget that in Cranach’s time, St. Valentine was also the saint to whom epileptics would pray, and in fact down at St. Valentine’s feet in Cranach’s painting one can see a man having an epileptic fit. Perhaps this rugged face fits better a saint who was meant to be dealing with epilepsy.

By coincidence, a few days later, at the Museum of the Lower Belvedere, I came across another painting with equally interesting faces. It is of three saints, Jerome, Leonard, and Nicholas. It is from the late 15th Century, painted by an unknown artist.

As I’ve noted in previous posts, I have a fascination for faces in art. When I visit most collections of Old Masters, after enduring a long series of paintings of classical figures prancing around in sylvan scenes or of various members of the nobility hamming it up in their best clothes, it comes as a relief for me to gaze upon portraits from times past. These are faces I can relate to, faces of people whom I could be seeing on any street corner on any day of the week, just dressed in different clothes. It reminds me that history is not some colourful story in a book but was the lived experience of people just like me.

Most of the faces I gaze on are pleasant; I look, I note, I move on. But sometimes – like St. Valentine’s – they are arresting. There is something about the face that holds my gaze, that makes me stop and look more closely, that makes me wonder what the person was like. Let me use the rest of this post to celebrate some of these arresting faces in art.

A good example is Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. I am particularly fond of this portrait of him, by Albrecht Dürer, painted a few years after Cranach’s St. Valentine.

It’s another painting my wife and I saw as we took refuge from the cold in Vienna’s museums, this time in the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

There are many other portraits of Maximilian, and in some of them he is frankly ugly, like this one of him and his family. With this side pose, his very prominent nose stands out.

Maximilian certainly looks better than many of his successors, who sported the monstrous Hapsburg jaw. It seems to have started with his grandson Charles V, who is in that last painting, bottom centre. It continued down the generations. Here is a portrait of Charles V when young.

In later life, he grew a beard, presumably to camouflage the chin.

But I don’t want to focus on ugly people, even though they are the subject of many, many paintings. So my next candidate for arresting faces is Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino. Probably the most well-known portrait of him is this one in the Uffizi, in a double portrait with his wife Battista Sforza.

I prefer this portrait of him, though, where we see him together with his son Guidobaldo.

That is a really interestingly craggy face! It certainly mirrors his life, a man who was a brilliant condottiero but also a very cultured man: in the last painting, he is dressed in armour but he is reading a book, an allusion to his humanist interests. Of course, the thing most people almost immediately notice about his face is that notch at the top of his prominent nose. He lost his right eye in a joust (and probably smashed up the right side of his face in the process; he always had himself painted from the left). To be able to see better with his one remaining eye, especially when fighting, he had the top of his nose cut away. A tough, tough guy …

Staying in Italy, the next arresting face I pull up is that of Lorenzo de Medici, il Magnifico. Of the many representations that were made of him, I choose this terracotta statue, whose brooding look captures me. What dark secrets are hidden there!

Other arresting faces come from Caravaggio. It’s the faces of the secondary characters in his paintings who most draw my eye. A prime example is the Incredulity of Saint Thomas. Look at the weatherbeaten faces of those three apostles! They could truly be fishermen walking the shores of the Sea of Galilee, or indeed any shores anywhere.

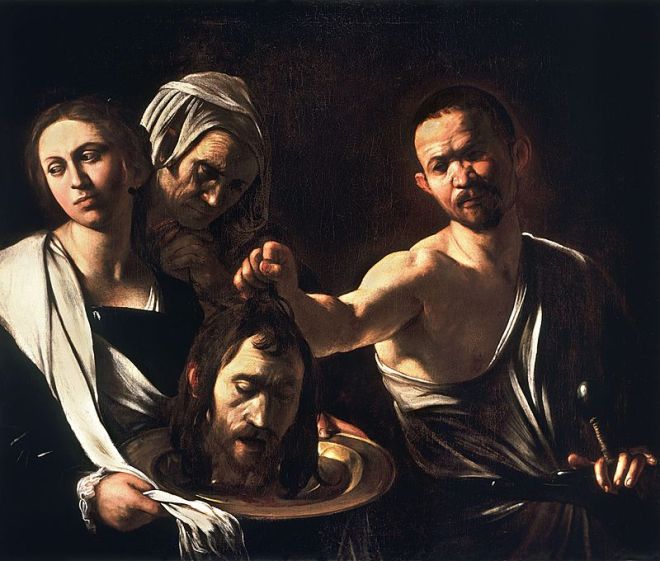

Or his Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist. Look at the face of the executioner!

It’s a face which reminds me of Michelangelo’s, another arresting face.

Personally, I’ve always loved this self-portrait, where Michelangelo included himself as Nicodemus in the Deposition, a sculpture I first saw in Florence decades and decades ago on my first trip to Italy.

Michelangelo’s badly broken nose adds to the allure of his face. I read a while back that it got broken after he mocked the drawings of the artist Pietro Torrigiano, who in a rage took a swing at him.

I can’t leave Italy without including a portrait of San Carlo Borromeo, cardinal archbishop of Milan.

His large nose led the Milanese to nickname him Il Nason, Big Nose.

Readers will see that it’s all been men up to now. Indeed, it’s been very hard to find paintings of women’s faces which are arresting: beautiful yes, haughty yes, homely yes, motherly yes, careworn yes, but arresting …

After a considerable amount of searching, I came up with a few examples. This is Mary, Queen of England.

Now that is the face of a very determined woman! And determined she was. She suffered through all the travails of her father Henry VIII declaring her illegitimate, banishing her from court, and refusing to let her be with her mother when she died, and, once on the throne, she tried with all her might to bring England back into the Catholic fold.

And this is her half-sister Elizabeth I.

She, too, suffered under Henry VIII, nearly losing her head at one point, and when she was queen had to navigate tempestuous religious factional fighting. She was not a woman to be pushed around.

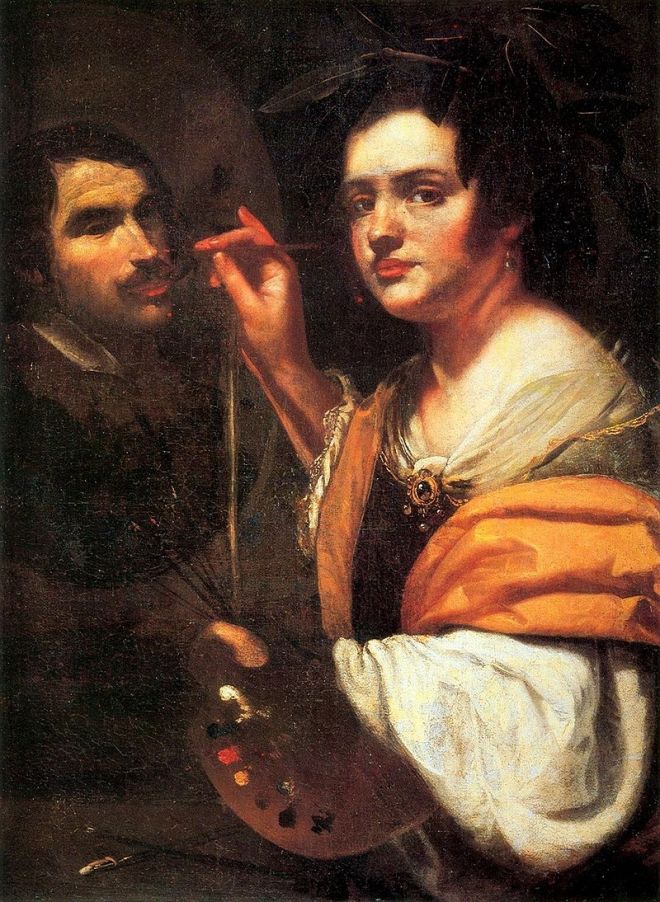

Perhaps I could add this self-portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi. It’s not a face that necessarily arrests me, but knowing her background – raped when she was young by another painter, tortured during his trial for rape to see if she kept to her story, having to see her rapist’s meagre two-year sentence reversed after a short prison term – I sense a steeliness in her.

I finish with the face of a peasant woman in an early painting by Van Gogh, before he went to Paris. It’s from the Potato Eaters, a really dark painting (literally).

It’s the woman on the far right that intrigues me. I show a blow-up (I’ve also lightened it a bit).

Now that’s an arresting face!