Milan, 21 April 2024

It’s the Salone del Mobile this week in Milan, the annual furniture and furnishings fair that the city hosts. As proud citizens of Milan (well, adopted citizen in my case) my wife and I take part in the fair – but only marginally, because there’s a huge amount of events all over town, and outside of town as we shall see, and hordes of people visiting each event. In fact, this year we have only visited one exhibition, which is taking place in Varedo, a small town on the outskirts of Milan. Varedo is best known for a huge factory it once hosted which made artificial textile fibres until it folded in 1999. It was part of the SNIA Viscosa group, which itself went belly-up in 2010 after a long agony. All that is left of the Varedo factory are mouldering industrial buildings: a sad reminder of the deindustrialisation of Europe.

The exhibition was taking place at the other end of the town, in the villa Bagatti Valsecchi, which 100 years ago had been the country house of one of the elite families of Milan, the Bagatti Valsecchi.

It didn’t look too bad from the outside, but that statue gives a premonition of what the inside looked like: it too was a mouldering mess, although at least the floors were still in place.

I haven’t managed to find out what happened exactly to the villa, but I assume it’s the same as what happened to many country houses in the UK: it simply became too expensive for the Bagatti Valsecchi family to maintain it. They “generously” donated the house and property to the municipal government, but I suspect this was a poisoned gift. The municipality certainly has done very little if anything to maintain it.

Of course, it’s edgily chic, is it not, to showcase new, shiny, cutting-edge design in mouldering rooms. Here’s the thing, though. The furniture and furnishings my wife and I were confronted with as we wandered from room to room might have been newly minted, straight from the designers’ workshops, but to my mind the design ideas behind them were as mouldering as the rooms they sat in. Nothing new, just the same old ideas we’ve been seeing for 30 years or more recycled, endlessly recycled.

The one fresh design we came across was down in the basement, in a dark, dank room. Which was OK, since the product in question was lighting. Here is what we found ourselves in front of.

Some words of explanation are required here. The design group behind this is Spanish, going by the name Fernando Diaz de Mendoza 9, or FDdM9 for short. This particular design idea came about through the merging of the need to find ways to cleverly recycle PET bottles, on the one hand, and the desire to support traditional weaving skills still in existence in various parts of the world, on the other. The result was a project which the group calls PET Lamps.

The project started by making lampshades for single ceiling lights. The clever thing was that they were using PET bottles as the lampshades’ basic infrastructure: a component that is now free pretty much everywhere in the world since we are drowning in waste PET bottles. The mouth and shoulders of the PET bottles play the role of the fitting at the top of a traditional lampshade. Through it runs the wire and light bulb socket. What’s more interesting is what happens to the rest of the bottle. It is sliced into thin strips, and then the strips are used as the initial warp for weaving the weft across. What type of weft gets used depends on the weavers with whom the group is working.

The group started by working with weavers from the Eperara-Siapidara indigenous community in Colombia, who use the stripped down leaves of the Paja Tetara palm tree dyed with natural pigments and adopted traditional motifs.

They also worked with a community which weaved with wicker, a plant imported by the Spaniards.

They worked, too, with other communities in Colombia and Chile, but I’ll jump to Ethiopia, where FDdM9 collaborated with weavers of traditional coiled baskets from the city of Harar, to make lampshades like this.

Here’s an example of a cluster of these lamps being used in a restaurant.

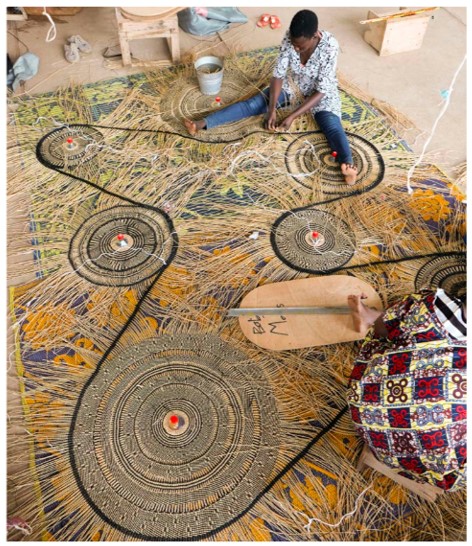

I’ll skip the lampshade designs which the group collaborated on with weavers in Japan and Thailand; readers who are interested can go to the Pet Lamp website. I’ll go on to the designs they created with the Gurunsi people who live in the far north of Ghana. Together with them, they came up with a modern take on their basket weaving designs to create “wavy” lampshades. Here are the weavers at work (the weft in this case is elephant grass, by the way).

And here is an example of the final product.

While here we have a cluster of these lamps being used over a table.

Before going on with Ghana, I want to jump to Australia, where to my mind things started to get really interesting. There, FDdM9 started collaborating with weavers in Arnhem Land, in the far north of the country (I mentioned other Australian weavers in a previous post). The weavers started by making individual lampshades with designs based on their traditional mats.

But then one of the weavers began linking two lampshades together, which led the weavers to link all their lampshades together, in a way that reflected their kinship relations.

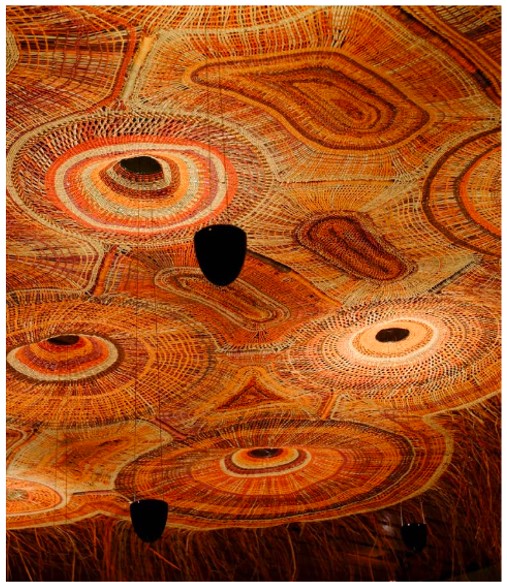

It gave this as a final product.

This is what it looks like when it is put up.

Which brings me back to Ghana. Several years after their initial collaboration with the Gurunsi people, FDdM9 went back to create large-scale “lamp tapestries” (I can’t think what else to call them) similar to those they had helped to create in Australia. Whereas the design of the tapestries in Australia were based on kinship relationships between the weavers, the designs in Ghana were based on aerial views of the houses where the weavers lived (which is actually also a representation of kinship relations if you think about it, since children built their houses next to their parents’).

Here we have the weavers at work.

And here we have a final product.

I suppose FDdM9 would expect these lamp-tapestries to be used like this.

But that’s not the way my wife and I would like to use them. We would prefer to eliminate the lamps and use the tapestry as a wall hanging, as we saw in that damp, dank cellar in Villa Bagatti Valsecchi. And we have just the wall where we could put it! Of course, the price might be an issue: one of these lamp tapestries would set us back a cool €17,800. But you have to suffer for great art! (still, though, €17,800 …)