Milan, 13 January 2025

My wife and I were recently listening to an article from the New York Times about an Egyptian immigrant to New York, by the name of Armia Khalil. Mr. Khalil had been an artist in Egypt. He liked to create pieces that echoed the country’s ancient artefacts. He did so using tools he had created that were similar to those used by the Ancient Egyptians themselves. Of course, when Mr. Khalil arrived in New York, with a suitcase crammed with his tools but with hardly two nickels to rub together, he didn’t have the luxury to use them; he needed a job. But he didn’t want any old job. He wanted a job that brought him close to art. So he applied over and over again for jobs as a museum guard to the city’s many museums; he reasoned that at least this would allow him rub shoulders with art all day. Finally, after six years of trying, he managed to unhook a museum guard job at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Readers can read (or hear) the rest of his delightfully heart-warming story in the original New York Times article, if they can get around the paper’s firewall. If not, they can visit his WordPress blog – it gives me great pleasure to advertise a fellow WordPress blogger.

Mr. Khalil’s repeated attempts to be hired as a museum guard to get close to art brought back fond memories for me. Because I had tried to do the same many, many years ago. It was January, I was 18, I was staying with my parents in Ottawa for five months until the beginning of June, I needed to find something to do. Whenever I had spent the holidays with my parents, I had always found the time to visit Canada’s National Gallery. This is the building I used to visit, back in the early 1970s, although I see it has now moved into a sparkling new building somewhere else in Ottawa.

I found the time I spent there most soothing. I thought, why not spend my five months in Ottawa, sitting on a chair in the Gallery’s exhibition rooms and admiring the art around me? So I got myself an appointment with the head of the guards and arrived promptly for the interview. It was in a dreary, windowless office somewhere in the basement of the building. He was sitting at his desk, flanked by one of his guards. He invited me to sit down. He looked me over. Then, with great frankness, he told me why he doubted that I was right for the job. He pointed out that I was much more educated than the other guards, so had I thought about what my social interactions with them would be like? (the implication being, no doubt, that I would be awfully lonely during the working day, with no colleagues to really speak to). Did I not think, he continued, that I was far too young to get stuck in what was, at the end of the day, a pretty boring job? His basic message, I felt, was that it was best to be ignorant, probably stupid, and old before accepting a dead-end job as a museum guard. His side-kick nodded throughout this analysis, which was sad because at the end of the day his chief was talking about him. Thinking about it now, he could have been describing Mr. Bean working at the Royal National Gallery in London, in the film Bean.

My interview was terminated with a final parting shot. The chief pointed to my fashionably long hair and regretfully informed me I would have to cut it, to conform to the short-back-and-sides style sported by the (male) guards. Crestfallen, I left without a job. Unlike Mr. Khalil, I did not try other museums or art galleries in Ottawa.

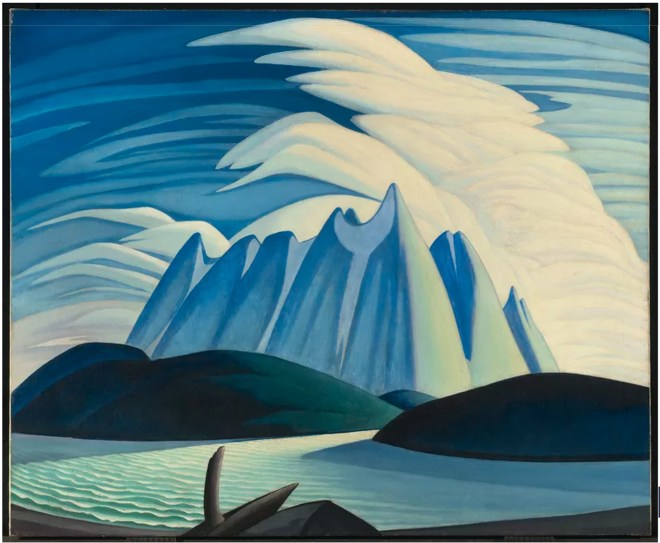

It was actually just a couple of rooms in the National Gallery that I would particularly have wanted to sit in as a guard, using my time to admire the paintings. They were dedicated to the Group of Seven, a coalition of Canadian painters who came together from shortly after World War I to the early 1930s. They were looking for a style of landscape painting that was distinctly Canadian and modern. To my mind, they succeeded brilliantly, with Lawren Harris being the jewel in the crown. His iconic painting, North Shore, Lake Superior, painted in 1926, is in the National Gallery.

But he painted many other wonderful paintings. Here is a selection. This first painting, Northern Lake, is from around 1923, early on in the Group of Seven’s life.

This painting, from around 1924, is another whose subject is Lake Superior: Pic Island.

At some point in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Harris went to Canada’s far north and even to Greenland. The results of these expeditions were a long series of almost abstract paintings of great beauty. I show only three here. The first two hang on our walls in Vienna in the form of prints (I am not, alas, rich enough to be able to afford an original Lawren Harris).

This one is titled Lake and Mountains, from 1928.

And this one is Mt Lefroy from 1930.

The final painting I show from Lawren Harris is Icebergs, Davis Strait, also from 1930.

Perhaps not surprisingly, in later decades Harris veered off into abstraction. I haven’t followed him there; abstract art is not really my thing.

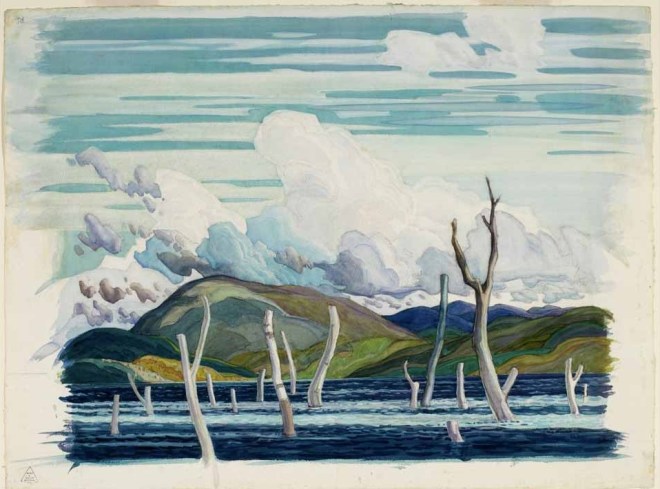

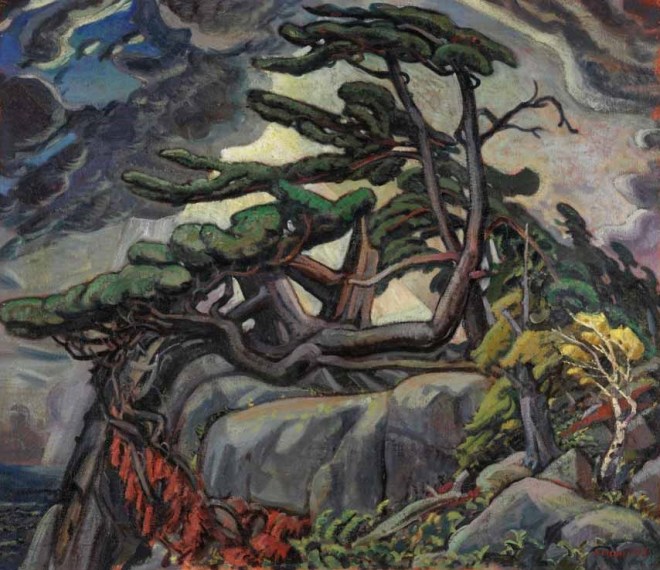

While I particularly admire Harris, the paintings of the other members of the Group of Seven are not be sniffed at. I give one example for each of them.

Franklin Carmichael, Wabajisik Drowned Lake, from 1929.

A.Y. Jackson, Barns, from 1926.

Frank Johnston, The Fire Ranger, from 1921.

Arthur Lismer, Pine Wrack, from 1933.

J.E.H. MacDonald, Algoma Waterfall, 1920

Frederick Varley, Stormy Weather, Georgian Bay, from 1921.

After all these years, I still don’t know if I would have enjoyed spending five months next to the paintings of this group of artists, or if I would have been bored to tears by the company of my fellow guards, or both. For any readers who might be asking themselves what I did end up doing those five months, I can reveal that I went to work for the YM/YWCA. I replaced a guy who had to go on a long sick leave, so it was a perfect fit. My job was to hand out stationary to the staff and to print the various flyers which they produced. I became a dab hand at offset printing, even if I say so myself – a skill, alas, I was never able to put to good use again.