Milan, 30 October 2025

The genesis of this post was a hike my wife and I did back in May, around the Danube not too far from Linz. As I relate in the post I wrote about that hike, one stop we made was at the small church in the village of Pupping. And there I found, among other things, this wooden statue of Saint Christopher.

The statue caught my attention because of Saint Christopher’s expression; as I wrote in the post, the Saint looks less than pleased with the Child Jesus sitting on his shoulder. In fact, I would go so far as to say that he looks downright grumpy. A nice take, I thought, on the traditional story about St. Christopher, and normally the only story that most people have ever heard about the Saint. So I made a mental note to come back one day to this Saint’s story. On a drizzly afternoon in Milan, that day has come.

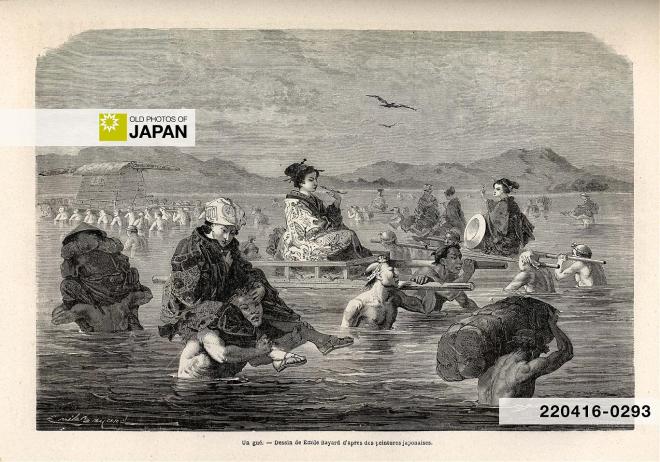

So what is the story that most people have heard about St. Christopher? I think a quick recap might be useful. I should start by noting a little-known fact, that at the beginning of the story our Saint was actually called Reprobus. He was a big, brawny man – a giant in many tellings of his life – and he was in this period of his life spending his time carrying people across a deep ford at a river somewhere in Asia Minor. In case any readers might think this surely was not a job people did in the old days – they would use a boat or a raft, right? – I throw in here a print of people doing precisely this in Japan in the 1860s.

In any event, one night Reprobus heard a young voice calling out. It turned out to be a child asking to be carried to the other side. So even though it was late Reprobus put the child on his shoulder, seized his trusty staff, and started crossing. To his consternation, as he waded across, the child got heavier and heavier. So heavy did the child get that this huge, strong man found himself struggling mightily to make it across. When he finally made it to the other side, he said to the child: “You put me in the greatest danger. I don’t think the whole world could have been as heavy on my shoulders as you were.” To which the child replied: “Don’t be surprised, Christopher [which in Greek means Carrier of Christ], you had on your shoulders not only the whole world but Him who made it. I am Christ your king, whom you are serving by this work.” Thus did Reprobus become Christopher. And no wonder Reprobus-about-to-become Christopher is looking so grumpy in that statue in the church in Pupping!

It is a charming story which got painted many times by numerous artists in Western Europe. I throw in here an assortment:

By the Master of the Pearl of Brabant

By the Flemish painter Joachim Patinir

By Rubens

In fact, it’s just about the only story of Christopher’s life that ever got painted in Western Europe, crowding out all the other stories associated with him.

I must confess, the precise theological messages of the story elude me, even though I have perused several posts trying to help me out. In fact, I read elsewhere that the story was actually made up by various churchmen to “normalise” what was a widespread practice by the “little people” of painting enormous portraits of St. Christopher with Christ, first inside their churches and then later on their outer walls. When I read that, I had a jolt of recognition. A couple of weeks before that hike around the Danube, my wife and I had hiked for a couple of days in the south of Austria in the hills around Villach. In some of the small villages we walked through I had noticed these giant St. Christophers painted on the outside of three of the village churches which we passed. I was so struck by them that I took several photos.

This is a general view of the church where I saw the first one

Here is a close-up of the fresco

This was in the next village we passed through

This was at the church where we sat down to have our sandwiches for lunch.

At the time, I had found these frescoes charming. I was now reading that they actually had a precise meaning. They were showing St. Christopher in his role as the “guardian from a bad death”, and especially a sudden and unexpected death. We have to plunge into the Christian mindset of the Middle Ages to understand why this was so vital. Any person who died “unshriven”, that is to say without having confessed and been absolved of their sins, was condemned to spend eternity in Hell without any possibility of salvation. And the torments of Hell were always well represented in church frescoes in case people forgot. Here is one such example, painted by Giotto in the Scrovegni chapel in Padova.

Under the circumstances, it made perfect sense for everyone to do whatever they could to avoid an unshriven death. Somehow, the belief sprang up that if you saw the image of St. Christopher you wouldn’t die that day. Thus the huge size of the St. Christophers as well as their location on the outside walls of village churches; like that, all villagers, even those living far from the church, avoided the risk of not seeing the image during the day. As one can imagine, the popularity of these images soared during the Black Death, when the risk of dying unshriven increased enormously. Continuing bouts of the plague over the centuries maintained their popularity.

I rather like this role of St. Christopher as a Gentle Giant keeping an eye on your lifespan. However, by the 15th Century, when huge St. Christophers had proliferated everywhere, theological and ecclesiastical authorities had become less enthusiastic, considering this trust of the “little people” in St. Christopher to be mere superstition. They were far more comfortable with the Saint’s role as the protector of travelers and all things travel-related (it was of course his role of carrying travelers across the river that led to travelers invoking his protection). And the coming of the automobile, where the dangers it posed to life and limb became immediately obvious, saw a huge increase in the Saint’s popularity. Even now, miniature statues of the Saint are frequently displayed in cars; sign of the times, you can buy one on Amazon. Yours for a mere $8.99!

Meanwhile, in Orthodox Christianity, things took a different path for Christopher. The whole story of him carrying the Boy Christ across a river was ignored (at least until relatively recently). Instead, the focus was on his good, Christian life after his baptism and his martyrdom. So the icons of him have a young man, normally dressed as a soldier. Here is an example from Saint Paraskevi Church in Adam.

So far, so bog-standard. But then, there is a startling alternative in his iconography, one where he is depicted as having a dog’s head (at least, I find this startling; showing saints with dog-heads seems rather disrespectful to me).

I find these icons so strange that I am moved to throw in the photo of another one, where St. Christopher is cheek by jowl with a perfectly normal St. Stephen.

This strand of iconography came about from a rather too literal reading of the legends about Christopher’s origins. It was said that he had been captured by Roman troops in combat against tribes dwelling to the west of Egypt in Cyrenaica. Already back in the 5th Century BCE the Greek historian Herodotus had written that in these parts, on the edges of the civilised world, lived dog-headed men as well as headless men whose eyes were in their chests. This belief in Europe that the edges of Europeans’ known world were populated by strange hybrid human species continued well into the early modern times, as this woodcut from the 1544 book Cosmographia shows.

As a consequence, some icon painters believed that Christopher (or Reprobus as we have seen he was then known) was dog-headed, and they painted him as such.

Not surprisingly, there was pushback on this depiction of Christopher from the Higher-Ups. In a 10th Century hagiography about the Saint, its author, Saint Nikodemos the Hagiorite, wrote: “Dog-headed means here that the Saint was ugly and disfigured in his face, and not that he completely had the form of a dog, as many uneducated painters depict him. His face was human, like all other humans, but it was ugly and monstrous and wild.” For its part, in the 18th century the Russian Orthodox Church forbade the depiction of the Saint with a dog head because of the association of such a representation with stories of werewolves or monstrous races.

Poor Christopher! Giant, dog-headed, and now cancelled. Because, back in 1969 the Catholic Church struck him from the General Roman Calendar, deeming that there wasn’t enough evidence to show that he had ever existed. I still remember the general consternation this caused at the time. What about all those miniature statues in cars (and medallions around necks)? How could they protect you if Christopher had never existed? I guess the fact that people continue to buy them shows that the “little people” will still believe in these images’ magical ability to protect, whatever the Higher-Ups say or do.