New York, 28 December 2015

I’ve described in a previous post the beautiful, and really very unique, High Line Park in New York. On our first visit to the park, we heard that the Whitney museum was planning to relocate from uptown to new premises bang on the High Line. Now, two years later, the plans have come to fruition, and since we are once again in town to celebrate Christmas and New Year with the children we decided to go and visit.

The building itself was designed by the architect Renzo Piano, he of the Centre Pompidou in Paris (along with fellow architect Richard Rogers)

and, less felicitously, of the Shard in London

along with a string of projects in between. The new Whitney is not as spectacular as these two, giving the impression of being more of a workmanlike project – how to give the museum lots of exhibition space – and blending in quite well with its surroundings.

One also gets beautiful views across the Hudson River from its windows.

Perhaps it’s just as well. I mean, the main purpose of going to a museum is not so much to see the container as to see what is contained (I grant, though, that a handsome packaging can add lustre to what’s in the package). So let me focus on the contents.

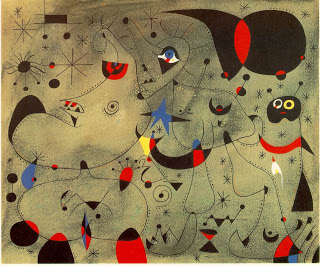

Actually, I don’t really want to focus on the contents as such, but rather use them to meditate on something which gets under my skin when it comes to really modern art – let’s say, stuff produced in the last sixty years i.e., during my lifetime.

I happen to think that the primary purpose of any piece of art should be to adorn one’s abode in a way that gladdens the heart and puts a spring in one’s step. The key, though, is that the piece of art should fit through the door of one’s abode and, once in, should fit on a wall of that abode (or, if a sculpture, on a small table or shelf). The core of the Whitney’s collection, from the ’30s and ’40s, would do this admirably. For instance, there was a lovely Hopper on view which would could be passed through the door of our apartment quite easily and would fit quite nicely on one of its walls.

It’s one of several delectable Hoppers in the collection. Or I wouldn’t mind at all putting this painting by Charles Demuth on our wall.

Getting it into the apartment would be a breeze – I think it could probably even fit it into the small elevator we have in our building, thus avoiding us having to carry it up three flights of stairs.

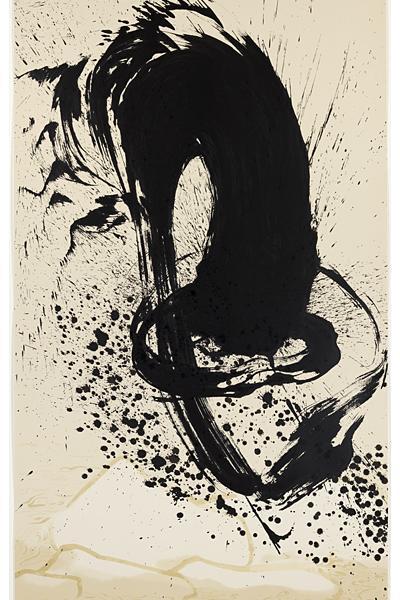

But as we get into the late ’50s, early ’60s, the pieces begin to grow. We would just about be able to manhandle this Pollock which the Whitney has through our apartment door, but I think we would have difficulty finding a place for it on the wall.

And this painting by his wife Lee Krasner would be impossible to hang in our apartment, it’s just too damned big let alone of a size to get through the door.

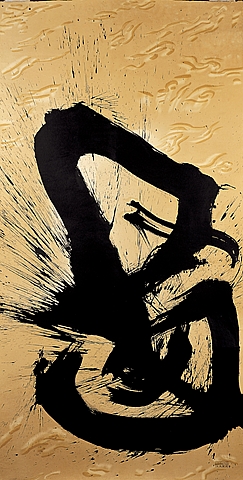

The pieces in the Frank Stella show which the Whitney is currently organizing were even worse. They were huge lumbering monsters, which would not even fit through the front doors of our apartment building, leave alone through the door of our apartment.

And even if by some miracle we got them into the apartment, many of his pieces jut out, making it hard to have any furniture around them.

Of course, given the stellar prices for modern art, only plutocrats can afford to buy these pieces. But do even they live in such palatial abodes as to make it possible for such a piece to fit snugly in the living room, say? I find it hard to believe.

I can only assume that much modern art is either made for large and powerful multinational corporations, whose huge atriums or corporate boardrooms in their Headquarters have enough space for such pieces

or it is made for museums such as the Whitney which have large exhibition spaces. Either way, art for the people it is not. And that’s a pity, because at the end of the day art should be for us, something which we can hang on our wall and admire for decades or even centuries before perhaps donating it to a museum.

I think it’s time for a new art movement, the FOTS (“Fits Over The Sofa”) movement.

_____________________

Centre Pompidou: http://www.leparis.pl/centre-georges-pompidou-muzeum-sztuki-wspolczesnej/

The Shard: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renzo_Piano

The Whitney (both views): http://whitney.org/About/NewBuilding

View across the Hudson: http://elizabethbarton.blogspot.com

Edward Hopper “Early Sunday Morning”: http://collection.whitney.org/artist/621/EdwardHopper

Charles Demuth “My Egypt”: http://collection.whitney.org/object/635

Jackson Pollock “Number 27, 1950”: http://www.allartnews.com/pollock-and-the-irascibles-the-new-york-school-opens-at-palazzo-reale-in-milan/

Lee Krasner “The Seasons”: http://www.brooklynstreetart.com/theblog/2015/04/30/the-new-whitney-opens-may-1-america-is-hard-to-see/#.VoE8i3o8KrU

Frank Stella: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/30/arts/design/tracking-frank-stellas-restless-migrations-from-painting-and-beyond.html?_r=0

Frank Stella: http://www.hedgefundintelligence.com/Article/3503103/Steve-Cohen-sponsors-Frank-Stella-exhibition-at-the-Whitney-Museum.html

Headquarter atrium art: http://houston.culturemap.com/news/entertainment/03-02-13-image-bending-spanish-artist-transforms-downtown-houston-office-atrium-with-iwavesi/slideshow/

Corporate boardroom art: http://www.artworks-solutions.com/news/view/corporate-art-works

Space over sofa: http://www.utrdecorating.com/blog/hanging-pictures-sofa/