Milan, 14 January 2026

There is an expression in Italian which goes like this: “Whoever does X on the first of the year will do X for the whole of the year”, where X can be anything you would like to do (or should do) throughout the year. Well, it wasn’t the first the year, but it was pretty close when my wife and I visited an art exhibition, hopefully a herald of many more visits to art exhibitions during 2026 .

The exhibition in question, at Milan’s Galleria d’Arte Moderna, was not one of those blockbuster affairs covering an incredibly famous artist and attracting droves of visitors. It centred on the Italian artist Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, who was born in 1868 and died in 1907. Here is a self-portrait of the man, a painting which greeted us when we stepped into the first room of the exhibition.

I will perfectly understand if any of my readers confess to never having heard of this artist. I had never heard of him before I came to Italy, and I was to live in Italy quite a number of years before I came across him. If he is known at all, it is because of one, magnificent, painting. It was in the exhibition, but at the very end. So let me first show my readers a selection of his works that my wife and I passed as we wandered along through the exhibition. The paintings were hung in more or less chronological order, so we could appreciate how his style developed over the years.

An old man, a certain Signore Giuseppe Giani, staring out at us solemnly.

Executed in 1891, the painting’s formal title is “Il Mediatore”, which I think would be translated as broker or agent. Not sure what Signor Giani would have brokered: land deals, perhaps? Very classical in its execution, I would say.

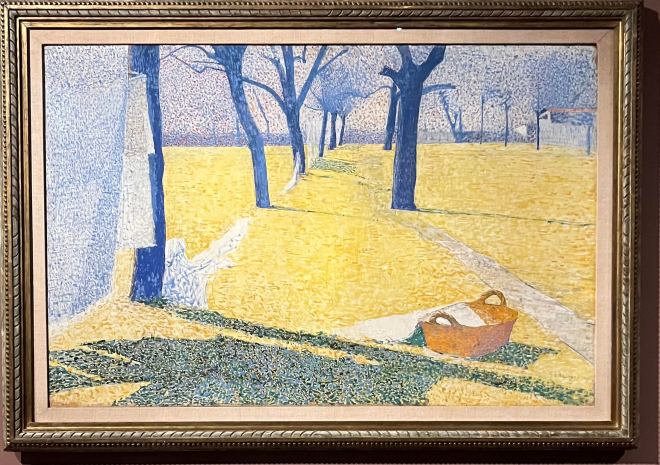

“Panni al Sole”, Washing in the Sun, painted a few years later, in 1894-5, when Pellizza was intensively exploring Divisionism, Italy’s response to Pointillism.

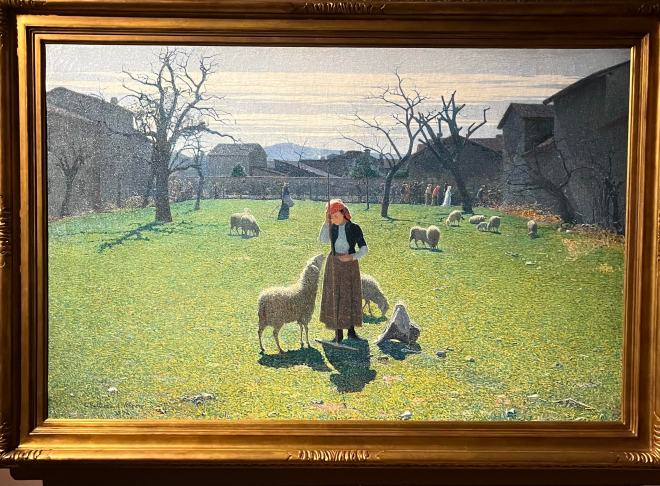

Those predominantly yellow hues in the painting remind me of an exhibition of Dutch pointillists which my wife and I saw a few years ago in Vienna. Unfortunately, although Pellizza used divisionism in all of his paintings from this moment on, he didn’t follow the more modern painters of the age. His subjects always tended to the sucrose. The exhibition notes called this style Symbolism. Maybe they were full of symbolism, but I couldn’t get away from the chocolate-box feeling of his paintings. Here we have “Speranze Deluse”, Dashed Hopes, painted in 1894, so at the same time as “Panni al Sole”.

And here we have a series of three paintings , all titled “l’Amore nella Vita”, Love in Life, painted between 1901 and 1903.

The summer of young love, the autumn of middle-aged love, the winter of old love. As I say, rather sucrose – although as a person who is now an oldie I gazed at the old love and saw something I suppose we oldies all fear, the loss of the partner of a lifetime and the loneliness of the last years.

After all the sugar, it was relief to find this painting in the next room, a sober rendition of snow, from 1905-06.

Turning around, this painting from 1904 had me pause. It is of the rising sun, at that moment when it appears over the horizon in a flash of brilliance. I feel Pellizza captured that moment very well (and by the way, his divisionist style is very noticeable in the sun’s rays).

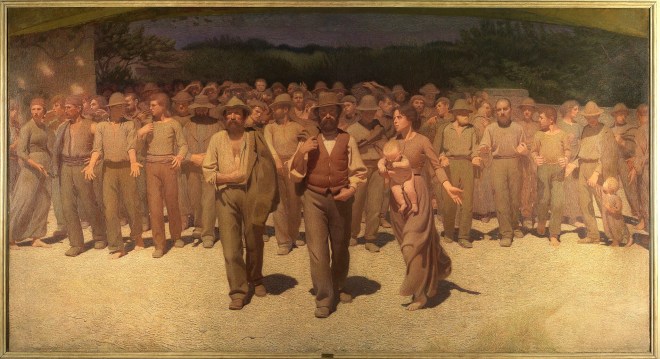

And so we moved on to the exhibition’s last painting, completed in 1901, the majestic “Quarto Stato”, The Fourth Estate.

A small photo like this doesn’t do justice to the original, which is 3m high by 5.5m wide. Nevertheless, it will have to do. The painting showcases workers marching, calmly and confidently, for their rights and into a bright future. The title takes up the idea that the proletariat which the Industrial Revolution created had become a fourth estate, adding to the three estates of aristocracy, clergy, and bourgeoisie which existed in pre-revolutionary France.

Initially, the painting was ignored. The Italian bourgeois, the ones who went to exhibitions and bought paintings, were turned off by a painting with such obvious socialist connotations. It stayed in the family’s possession. Then, in the early 1920s, at a time when Milan’s municipal government was strongly left-leaning, the government raised money to buy it. It was hung in Milan’s castle, the Castello Sforzesco, for all the world to see. Then, during the Fascist period, when Socialism was a dirty word, it was quietly rolled up and consigned to the castle’s basement, only to be fished out after the war and hung again, this time in Milan’s main municipal office. After which, it became very popular in left-leaning circles. Bernardo Bertolucci, for instance, in his film Novecento, which is a study of the agricultural working class in northern Italy over the first fifty years or so of the 20th Century, used a close-up of the painting as a backdrop for the film’s opening credits

while the painting itself acted as a background to the film’s poster.

Others on the left used the painting as a template to create their own images. Here is one, a group of people celebrating May 1st. They hold a red flag and have obviously copied the Quarto Stato in their composition.

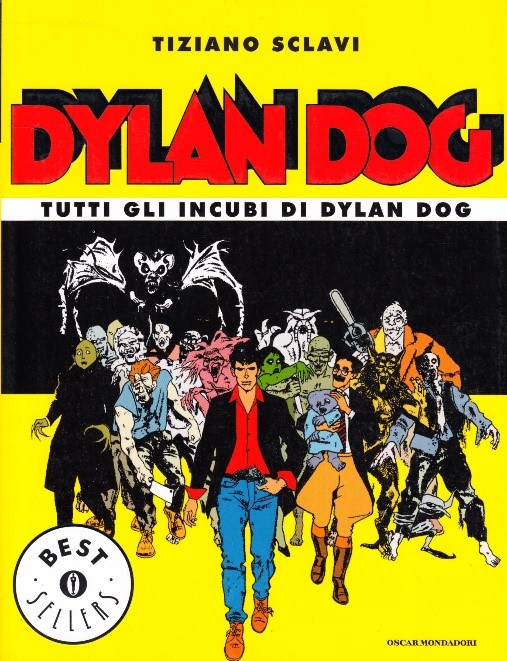

There have also been less serious uses of Quarto Stato. Dylan Dog, for instance, an iconic horror-mystery comics series very popular in Italy, used Quarto Stato’s composition many times over on its covers. Here is one from 1991.

It’s even been used in publicity. Here is an ad for Lavazza coffee from 2000.

I’m not sure what Pellizza would have thought of these trivialisations of his painting. He was a sincere Socialist. But I suppose all publicity is good publicity.

Just to finish Pellizza’s story. His wife – she is the model for the woman with the baby in the foreground of the painting – died in childbirth in 1907, together with the child. Soon after, Pellizza’s father died. In anguish, Pellizza committed suicide; he was just shy of his 39th birthday. Who knows what paintings he might have gone on to produce?

I’ve seen that Volpedo, the little town where he was born and where he spent much of his time, is quite easy to get to from Milan. One day, when the weather is warmer, I will try to persuade my wife to go there. It’s been crowned as one of Italy’s Most Beautiful Villages. I’m sure we can also find a nice hike to do in the surrounding hills.

In the meantime, we need to keep a weather eye out for other interesting art exhibitions to get us through the cold months.