Vienna, 20 July 2024

My wife and I recently had our annual check-up with our GP in Vienna. He’s been our doctor here for nigh on 20 years. The first thing he told us was that he was retiring at the end of the week. Tutto cambia, tutto su transforma, everything changes, everything is transformed, as I mournfully intoned in an earlier post. After he had given us our prescriptions for the routine blood and other tests we do every year (the results of which, though, will be reviewed this year by his partner in the medical practice), we chatted a bit about his retirement plans. He told us that he and his partner would be selling their apartment in Vienna (which is how we met him; they lived on the floor below ours), and they would be moving to a house which they have spent the last couple of years restoring, out in the countryside in southern Styria.

He was especially enthusiastic about its garden. He told us that he has filled it with all sorts of exotic plants, which have been flourishing. It doesn’t surprise me, he has exceedingly green fingers; we would gaze down with wonderment (and not a little envy) at the terrace of their apartment, a riot of flowers and plants, which he would lovingly curate in the evenings during the spring and summer. He told us with a note of pride in his voice that he had even successfully planted a pau-pau tree. A what tree, my wife and I both asked? After some toing and froing, we finally understood he was talking about a tree that produces a fruit called pawpaw. But the confusion wasn’t over yet. Since neither of us had ever heard of pawpaw fruits, my wife fished out her iPad and undertook a rapid Google search to see what they looked like. The search term “pawpaw” resulted in this image.

You mean papaya, we asked? This is what we call this fruit. No, no, our doctor said, not papayas; pawpaws. More Google searching and my wife came up with this.

Yes, the good doctor said, that’s the one.

Well, well, they say you learn something new every day (who coined that phrase, I wonder? Must Google it). My wife and I certainly did that day, along with the distressing news about our doctor’s retirement. After promising to visit the two of them in Styria one of these days, we said our emotional goodbyes.

Of course, I couldn’t leave it there. I was just like my little grandson picking at a scab (did I mention that he’s been staying with us?). I just had to find out more about this pawpaw. Which was fine, because it turned out to be a really interesting fruit.

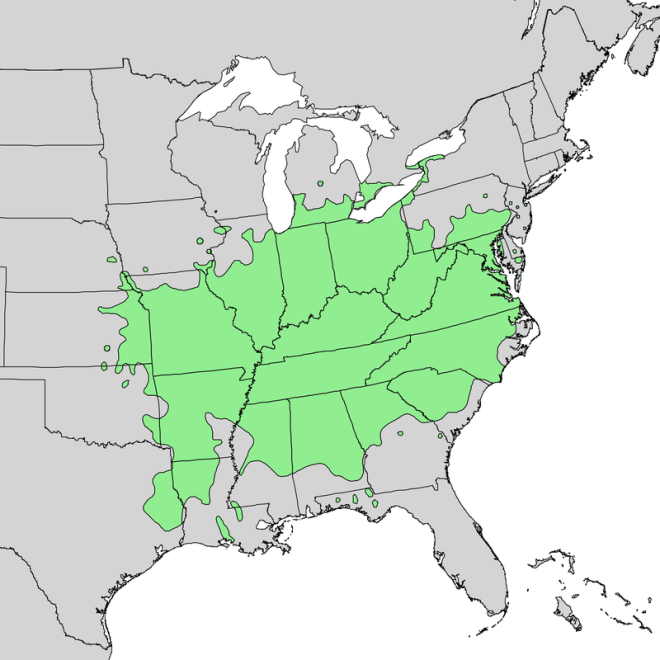

First of all, as this map shows, pawpaws are native to the US, and more specifically to the eastern, southern, and midwestern states – the push into southern Ontario is probably man-induced, as we shall see in a minute.

It’s intriguing that the pawpaw tree is found this far north, in temperate climes, because it actually belongs to a family nearly all of whose members are tropical. It’s a nice example of environmental adaptation. It would seem that the ancestor of the pawpaw developed on what is now the North American continent when the climate was tropical. As the climate cooled, the plant reacted by adapting to the chillier temperatures. Nevertheless, it never quite lost its earlier tropical “look”. Its leaves, for instance, have drip tips, a typical feature of tropical plants which are subjected to heavy rains.

And the fruit itself looks quite tropical; looking at the photo above one could easily mistake it for a mango, for instance.

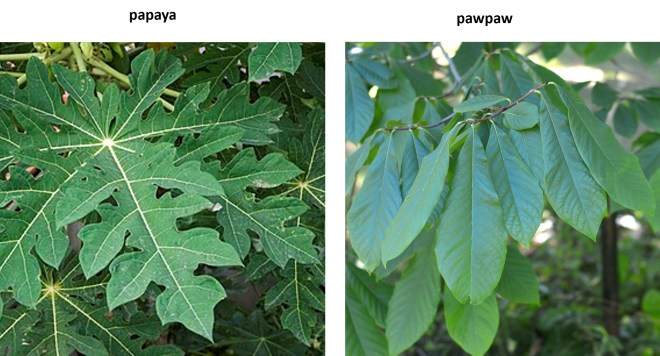

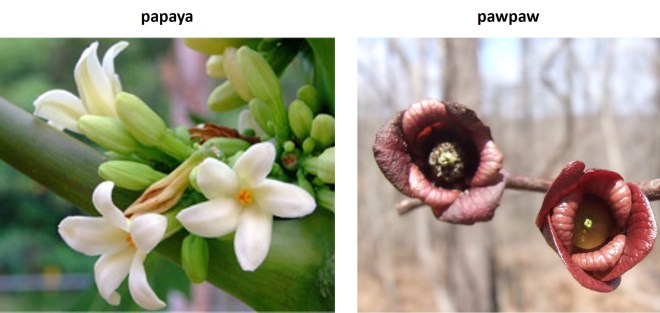

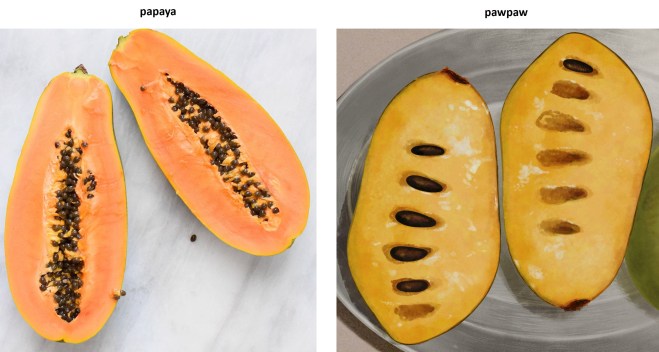

The name “pawpaw” is a bit of a puzzle. It seems that there was a confusion between the pawpaw and the papaya. Down in the British Caribbean colonies, the papaya was known as the pawpaw – and still today, in the UK and in many ex-British colonies, the papaya is called pawpaw. There was a brisk trade between the Caribbean and American colonies, and the thinking goes that when Brits coming from the Caribbean landed in the more southerly American colonies and first set eyes on this tree and its fruit they said “Ooh, look, those look like pawpaws” and the name stuck. Those Brits must have had very poor eyesight, though. In these next few photos, I invite my readers to compare various aspects of the two plants. Here’s what the tree looks like.

Here’s what the leaves look like

Here’s what the flower looks like.

Here’s what the fruits look like on the outside.

And here is what they look like on the inside.

I think my readers will agree that, with the possible exception of the whole fruits, the two really don’t look like each other at all. Maybe those Brits from the Caribbean were actually comparing the taste of the two fruits? For reasons that will become clear in a minute, neither I nor my wife have ever eaten pawpaw, so I am relying here on other people’s impressions of the fruit’s taste. This description, from its entry in Wikipedia, seems to summarise quite well various attempts I have found around the internet to describe the taste : “a flavour somewhat similar to banana, mango, and pineapple”. I haven’t eaten piles of papaya, but that description doesn’t fit with my sense of the papaya’s taste. I rather agree with one person’s assessment that the papaya tastes like a cross between a cantaloupe and a mango.

So the mystery remains: what the hell were those initial namers thinking?! They just created a big confusion. Why didn’t the colonists in the American colonies adopt the name given to the fruit by the local First Nations tribes? The Virginians did it with persimmons, after all (a transliteration of the Algonquian name for the fruit: “pessamin”).

The coureurs des bois (roamers of the woods), French Canadians who traded for furs with the First Nations and who were a key figure in the North American fur trade, were often the first Europeans to explore the part of the US which is the fruit’s natural range. They sensibly adopted the Algonquian name for the fruit, “assimin”, giving it a French twist, though, coming up with “asiminier”. Here we have an etching of a heroic-looking coureur des bois which appeared in a French Canadian magazine from 1871.

Taking a leaf from the Virginian colonists’ book, I shall start a campaign to have the fruit’s name changed to assimmon. Readers are welcome to join me in this futile tilting at windmills; just for the hell of it, I insert Picasso’s take on the original tilter at windmills, Don Quixote, with his faithful sidekick, Sancho Panchez.

I have to say, I do have a sort-of official approval for this effort: the plant’s proper botanical name is Asimina triloba, where the first part of the name picked up the coureurs des bois’s name. In fact, I shall start right now. I shall call the fruit assimon in the rest of this post.

As readers can imagine, the pawpaw – sorry, the assimon – was very popular with the First Nation tribes who occupied the fruit’s range. Here you have what turns out to be the largest edible fruit that is indigenous to the US, and it’s delicious to boot! The tribes loved it so much that they extended the fruit’s original range by carrying it with them when they moved into new territories (as they did with the Jerusalem artichoke – and of course maize). This most probably explains the fruit’s presence in Southern Ontario, brought there, it is theorised, by the Erie and Onondaga tribes. To bring us back to those far-off times, I throw in a photo of a figure that appeared in Samuel de Champlain’s books on his voyages in what is now Canada and the US. It relates to an attack Champlain carried out together with the Hurons on an Onondaga village, situated on what is now called Onondaga lake, close to the modern city of Syracuse in the northern New York State.

It’s lucky that the First Nations did move the assimon tree around, because it had evolved into a cul-de-sac. If readers go back to the photo of the open assimon fruit, they will notice its large stones. Fruit stones have evolved to be swallowed by the animals which consume the fruit, to be then expelled in a nice, fertilising pile of poo somewhere else as the animal in question wanders around. The bigger the fruit stone, the larger must be the animals eat the fruit – otherwise, they can’t swallow it. It’s been theorised that the assimon’s very large stone means that it evolved to be eaten by the American continent’s megafauna. Here is a photo of these large beasts, also showing humans, to give an idea of their enormous size.

Only the omnivores amongst them ate fruit, of course, but those which did spread the assimon around.

About 10,000 years ago, though, America’s megafauna died out. Quite why this happened is hotly debated, but the arrival of human beings, the ancestors of the First Nations, from across the Bering Straits was in all probability a big factor in this wave of extinctions. The modern bear is now the only animal big enough to swallow the stones of the assimon without choking. So it was just as well for the plant that humans stepped in and moved the plant around – and it was only fair that they did so, given the role they had played in the extinction of the megafauna.

As I said earlier, even though my wife and I lived something like eight years all told in the assimon’s range, we never tried it. We never even saw it being sold in supermarkets. How can it be that the US’s largest indigenous fruit is not readily available in every supermarket in the country? How can it be that enterprising Americans didn’t bring the plant to Europe, China, Japan, and anywhere else with the same temperate climate and establish assimon orchards?

The sad fact is that the assimon, in contrast to more popular – and non-American – commercial fruits like apples, pears, or peaches, stores poorly, primarily because the fruit ripens to the point of fermentation very quickly after it is picked. An assimon only keeps for 2–3 days at room temperature, about double that if it is refrigerated. This short shelf-life and therefore difficulty in shipping the fruit any distance means that the food industry is simply not interested in it. I have commented unfavourably in an earlier post about the fact that many of the foodstuffs eaten in the US are not native there, suggesting that native foodstuffs should be eaten. But in this case it really seems that the assimon is simply unsuited to our modern way of life. The best one can hope for is to find it in farmers’ markets held in the fruit’s range. And they will only offer it during the month of September, which is when the fruit ripens (there is a niche market for the shipping of the fruit over longer distances, but it must be a risky business).

Or you plant a tree in your garden if you live in the right climate. Which brings me back to my good doctor! We said we would go and see them. Maybe we could go and see them in September, when his assimons are ripe. But we need to know very precisely when they are ripe and then immediately go down to visit them and try this delectable fruit. But how to do this without sounding crass? “Hello, are your assimons ripe? If not, we’re not interested in coming.” I shall have to discuss this with my wife and try and find a more subtle way of doing this.