Milan, 18 March 2025

My wife and I recently went to an exhibition at the Gallerie d’Italia, a relatively new museum in Milan which is situated right next to the Scala. The exhibition’s title, “The Genius of Milan. Crossroads of the Arts from the Cathedral Workshop to the Twentieth Century”, didn’t really reveal what the exhibition was about, and I’m not sure I had any better idea after our visit. I think it was trying to show how many non-Milanese artists had come to Milan over the centuries and flourished there, but I wouldn’t swear to it.

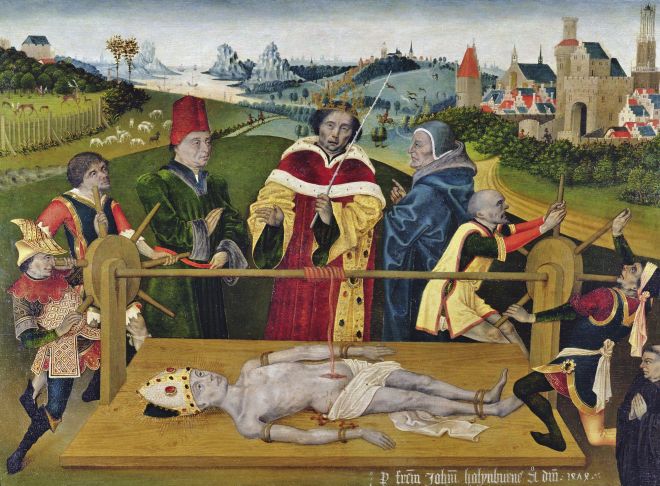

In any event, at some point I was suddenly transfixed by this painting, which shows in horrible, gory detail some poor guy having his entrails pulled out of him and wound around some contraption or other.

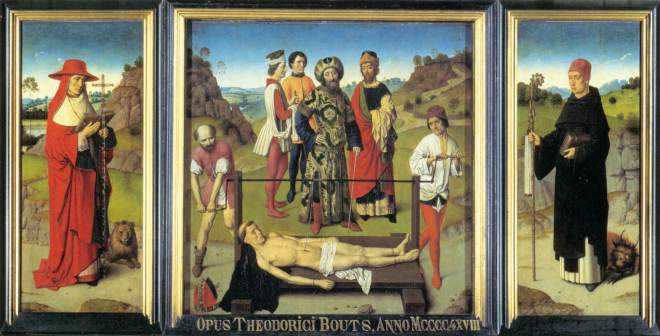

The painting’s label helpfully informed me that the poor guy in question was Saint Erasmus and he was being martyred. It was clearly a popular subject, because there was another painting just across the way about the same thing.

I’ve mentioned in past posts that early and Medieval Christians loved dreaming up horrible deaths for martyrs, but this one really took the biscuit! What sadistic mind came up with this one? And how did this particular form of torture even cross their mind?! I had, of course, to do some research.

As usual, as written up in the various pious hagiographies which appeared from at least the 5th Century onwards, St. Erasmus’s life seems to be one long muddle. So I’m going to more or less ignore these and sketch out what I think happened, not so much to Erasmus himself as to the legends which clustered around him and to the way he was portrayed in paintings.

It would seem that Erasmus started out as a local saint in the city of Formiae, a Roman port city some 90 km up the coast from Naples. Perhaps he was a bishop there. Bishop or no, there is a good chance that he was martyred in the city during Emperor Diocletian’s campaign of persecution, which ran with differing degrees of intensity from 303 AD to 313 AD. In later centuries, when relics of martyrs and saints became so important, his remains must have been reverently kept by the citizens of Formiae. Probably, too, to bolster the importance of his relics, legends about wondrous deeds performed by Erasmus began to circulate. One of these, which is important for our story, has him continuing to preach even after a thunderbolt struck the ground beside him. By the 5th Century, manuscripts also relating his nasty, vicious martyrdom at the hands of various Emperors were already circulating.

In the meantime, back in the real world, things were not going too well for Formiae. After suffering badly at the hands of the barbarians who flowed into Italy during the death throes of the western Roman Empire, it was razed to the ground in 842 AD by “Saracen” pirates who came from the sea. Its citizens ran – literally – for the hills, and that was the end of Formiae. Luckily, before the city was finally trashed, Erasmus’s precious relics were transported over the bay to nearby Gaeta, which was located on a much more defensible position, as this photo shows, and managed to hold off the pirates.

The relics are held to this day in Gaeta’s cathedral, along with the relics of four or five other saints, in a large crypt built in the early 17th Century.

In the 9th Century, when the relics were transferred from Formiae, and for a few centuries thereafter, Gaeta was a marine republic, like the ones on the Sorrentine peninsula further south, and very much in competition with them. Shipping was the backbone of the city’s prosperity, and the city’s sailors adopted Erasmus – one of Gaeta’s patron saints now that they owned his relics – as their personal patron saint. It seems that they chose him on the basis of that story I mentioned earlier, of him being unperturbed by a lightning bolt hitting the ground next to him. One of the perils which sailors ran (and still run) were violent storms. It’s not surprising that so many of the ex-votos found in churches in port cities have as their subject a sailor who was saved during a storm.

During such storms their boats could get hit by lightning. And so Erasmus became one of the patron saints of sailors. In this guise, he was often associated with the crank of a windlass. This may seem odd to readers, but windlasses were used on boats to pull up or let out an anchor or other heavy weights. The heavy weight is tied to a rope, the rope – maybe threaded through a winch – is wound around a barrel, which sailors turn using a crank (K in the diagram below).

It looks like people simplified everything by just associating the crank with Erasmus.

St. Erasmus’s connection in the minds of sailors to lightning got them to also connect him to another electrical phenomenon which sailing ships were (and still are) subject to. In brief, during thunderstorms, when high-voltage differentials are present between the clouds and the ground, oxygen and nitrogen molecules in the air can get ionized around the point of any rod-like object and glow faintly blue or violet. Well, of course, sailing ships in the old days had lots of rod-like objects, like masts or spars or booms, and when conditions were right there would be a faint glow at the end of all these. Here is a print of an old sailing ship with these ghostly “flames” on the ends of its masts and spars.

And here is a modern photo of the phenomenon around a clipper ship, the Cutty Sark, moored on the Thames in London.

Well, of course, sailors knew nothing of the physics behind the phenomenon. They interpreted those little flames as meaning that St. Erasmus was protecting their ship, especially since the phenomenon often occurred before the thunder and lightning started. And so the phenomenon become known as St. Elmo’s Fire (Elmo being an Italian corruption of Erasmus).

In a parallel universe, various martyrologies continued to be published over the ages, full of the usual hideous tortures meted out to martyrs. But nothing yet about poor Erasmus’s entrails being pulled out of him. Then, in about 1260, a certain Jacobus de Voragine published his martyrology under the title The Golden Legend. His story about Erasmus recycled many of the tortures covered in previous martyrologies to which the saint had been subjected. But then, Jacobus slipped in a brand new torture. In his words (translated into English by Wynken de Worde in 1527):

“[…] the emperor […] waxed out of his wit for anger, and called with a loud voice like as he had been mad, and said: This is the devil, shall we not bring this caitiff to death? Then found he a counsel for to make a windlass, […] and they laid this holy martyr under the windlass all naked upon a table, and cut him upon his belly, and wound out his guts or bowels out of his blessed body.”

Here is how the scene was depicted in one of the early editions of the Golden Legend (in case any readers are interested, the two fellows on the left having their heads chopped off are Saints Processus and Martinian).

Now, I said at the beginning, how did this particular form of torture ever cross Jacobus’s or someone else’s mind? Well, it has been suggested – and it doesn’t sound improbable – that whoever dreamed it up found inspiration (if that’s the word) from the association of Erasmus with the crank of a windlass. Presumably they assumed that the windlass had to have something to do with his martyrdom. After all, the depictions of many martyrs have them holding the instruments of their torture. Saint Lawrence, for instance, leaning on the grill he was roasted on:

Or Saint Bartholomew carrying the knife with which he was flayed alive.

Or Saint Stephen, balancing on his head and shoulders the stones with which he was stoned to death.

But what could the torture be in Erasmus’s case? Well, what do we humans have that looks like ropes? Entrails! And so this novel form of torture was dreamed up.

Now, Jacobus’s list of tortures inflicted on poor Erasmus is really long: I count 19 in all. Many of them would have made very appropriate subjects for the gory paintings of martyrs so beloved by painters until quite recent times. And yet, the entrails being pulled out on the windlass really caught on; I have to assume it’s because that was the one torture that Jacobus had a picture of in his book. Here’s just a few examples I found on the internet.

This first version is a more sophisticated variant of the picture in The Golden Legend and had added the emperor, “waxed out of his wit for anger”, looking on.

This next version is quite similar, except that St. Erasmus’s bishop’s mitre has now been thoughtfully placed to one side.

In this next one, we’re beginning to get a bit more dramatic.

While this one, by Nicolas Poussin, has pushed the drama levels to stratospheric heights.

Other paintings, perhaps trying to avoid all the gruesomeness of these kinds of paintings, just had a thoughtful-looking Erasmus, dressed as a bishop, holding his crank around which his entrails have been tastefully wound. This next painting is an excellent example of the genre.

This focus on Erasmus’s guts and the acute pain he no doubt suffered having them drawn out had an interesting side-effect. I’ve mentioned in a previous post the Fourteen Holy Helpers who helped Medieval people deal with their physical trials and tribulations – the headaches, or the sore throats, or the epileptic fits, or … they suffered from. Well, Erasmus fit very well into this scheme of things! He was obviously the go-to Holy Helper for cases of stomach and intestinal illnesses.

I related in the postscript to a previous post that in a moment of weakness I had bought a painting on glass of the Fourteen Holy Helpers. All this research has allowed me to identify which of the Helpers in my painting is St. Erasmus. Here he is, with his crank and some of his intestines rolled around it. All this research I do does sometimes have benefits …