Vienna, 9 April 2022

One of my guilty pleasures (the weight! the diet!) is eating a rum baba with my tea in the afternoon when my wife and I have walked off the Monte di Portofino down to Santa Margherita. There’s a little café in the pedestrian zone there, which offers a variety of sweet pastries. One of these is rum baba. We always make a bee-line for the café, plonk ourselves down at one of the tables outside it, and order two teas – milk for my wife, lemon for me – and a rum baba for me (depending on the weight situation, my wife will either look on enviously, or take a bite, or order her own pastry). Ah, the silky, squishy, sugary deliciousness of it!!

I had my first rum baba at the age of 10 or thereabouts, one of the times I was staying with my English grandmother on the way to, or on the way back from, boarding school. She had bought two of them specially – I now rather suspect that she had a weakness for rum babas and used my presence as a good excuse to buy them. Apart from the deliciousness of them, there was the excitement of slurping down Something Forbidden: rum! A highly alcoholic drink, with thrilling connections to the most dubious characters, as I knew from reading Treasure Island (“Yo, ho, ho, and a bottle of rum” sang the pirates) and Tintin’s Rackam Le Rouge.

There was also the name, baba, which was satisfyingly quirky, vaguely evoking in my young mind something exotic.

After that momentous first time, I came across this pastry occasionally. I have a vague memory from my teenage years of my mother ordering one in a French high-end café, this time in its French form, le baba au rhum. But overall it has been quite a rarity in my culinary experiences, so it is a pleasure to have found a place where with relatively little effort I can sample this delight more frequently, in its Italian form, il babà.

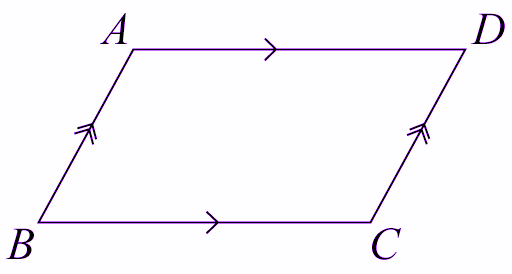

But what, some of my readers may be asking impatiently, is a rum baba?! It’s basically a small cake, made with Brewer’s yeast so that the dough will rise, which, after it is baked, is allowed to dry out a little and then is imbibed with a mix of sugar syrup and rum. The shape of the rum baba depends on the country: in France, it’s normally doughnut-shaped (ditto in the UK, because they copied all their ote kwizeen from the French). Note the heavy dose of Chantilly cream, which is often ladled onto rum babas.

The Italians, on the other hand, tend to make it mushroom-shaped (or like the cork of a champagne bottle). Note in this case, too, the heavy dose of cream.

And where was the rum baba invented, readers might also be asking? (at least, I hope they’re asking this vital question). Well, to answer that, I have to introduce my readers to a sad prince, Stanisław Leszczyński.

Born in 1677 into a high-ranking Polish family, he had the bad luck of being on the losing end of the perpetual political quarrels in Poland. His undoing was the Great War of the North, a war which involved Sweden on one side and Russia, Denmark, and Saxony on the other. Just for the hell of it, I throw in here a picture of a painting of one of the battles in this war; for some reason, these paintings always show officers prancing around on horses.

Charles XII of Sweden initially had the upper hand militarily. Among other things, he pushed out the-then King of Poland, August II (who was also Prince Elector of Saxony), and in 1704 put Leszczyński in his place with the dynastic name of Stanisław I. In 1709, however, Charles XII was soundly beaten by the Russians. The result was that August II was back on the Polish throne and Leszczyński was out on his ear. With his wife and two daughters in tow, he took the road to exile. In 1714, either out of pity or because he was a bit embarrassed, Charles XII let Leszczyński live in one of his holdings, the Palatinate of Zweibrücken, in what is now southern Germany close to the modern French border of Lorraine. Here, Leszczyński could live the life of a Prince Palatine of the Holy Roman Empire.

Alas, he was only allowed four years of the princely life. In 1718, Charles XII was killed still fighting the Great War of the North, the Palatinate passed to a cousin of his, and Leszczyński was once more out on his ear. This time, his neighbour the Duke of Lorraine came to the rescue and took him and his family in. But this could only be temporary and after some negotiations with the French Regent (Louis XV being under age at the time) Leszczyński was given a modest pension and allowed to settle on French territory. The place chosen was Wissembourg, a small town close to the far northern border of Alsace. It was 1719 and Leszczyński was to live there until 1725, surrounded by an ever-diminishing coterie of Polish nobles playing at being the Polish court in-exile.

Which brings us back to the rum baba. For it was in Wissembourg, in Leszczyński’s kitchens, that the rum baba, or rather its immediate ancestor, was born. Stanisław Leszczyński was probably not the best candidate for Polish king. That position needed a man of cunning and resourcefulness, with a ruthless streak, able to ride herd on the quarrelsome Polish nobles and juggle the competing aggressions of the countries surrounding Poland. That was not Leszczyński. He was a Man of Letters, at home in libraries (of which he built several during his lifetime) and author of a book or two. He saw himself as an Ambassador of the Enlightenment, writing various philosophical essays to promote its ideas. He was also a bon vivant, as the French say, a man who liked the pleasures of the flesh, particularly his food. With his modest pension, he couldn’t afford the best cooks, but his staff did what they could with what was locally on offer. Luckily for us, they hired a young Alsatian from the local region who went by the name of Nicolas Stohrer. He was 14 when he entered Leszczyński’s kitchens as a kitchen boy, but he must have been pretty damned good because he quickly became the chef in charge of cold and hot pastries and stews and desserts. Unfortunately, Stohrer left no pictures of himself behind, at least not on the internet, so I’m afraid readers will just have to imagine what he might have looked like.

One of the desserts Leszczyński loved was kougelhopf, a local Alsatian cake.

It’s actually a cake that is found throughout a wide swathe of Central Europe, from southern Germany through Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, and the ex-Yugoslavian countries, to the Czech Republic and Poland. It goes by various names; my wife and I know it as Gugelhupf, its name in Austria, which is where we first came across it (and I can certainly understand why Stanisław loved it so much, for it is indeed a very yummy cake). Important for our story, in Poland this cake is known as babka, or by the diminutive baba. And Leszczyński loved his kougelhopf in part because it reminded him of the baba he used to eat in Poland: like many exiles and immigrants, he no doubt found comfort in food from the Old Country.

The story goes that one day Leszczyński found his kougelhopf too dry (one source adds that he had lost his teeth by now, making it difficult for him to eat anything hard; a nice touch, but I’m not sure how much to believe it). He reminisced out loud – presumably in the presence of Stohrer – of how in the Old Country one sometimes drenched the baba in tokay wine from Hungary. Inspired by this tale, Stohrer went off to the kitchen, played around with the kougelhof, and eventually came up with the idea of a smaller cake, left to dry out a little, which could then be drenched by diners with a sauce based on fortified wine – here, the sources diverge somewhat: some say Madeira wine, others Malaga wine, yet others a mix of Malaga wine and an infusion of Tansy (for those readers who, like me before writing this post, have no idea what Tansy is, it’s a plant with a rather nice yellow flower which can be steeped in alcohol to give an infusion with a strong, camphor-like and bitter taste; no doubt it was used in small quantities to give sweet things a slight edge). To (literally) top off this creation, diners would add a (large) dollop of crème pâtissière, which is a thicker form of custard.

Leszczyński just loved this new cake. When asked by Stohrer what to name it, he declared it should be known as baba. One half of rum baba’s name was now in place.

Leszczyński’s family loved it too; in fact, more than 100 years later (and just a few years after the rum baba was finally invented in its entirety), a writer reported that Leszczyński’s descendants still served the dessert the original way, with a sauce boat being handed around and diners liberally saucing the cake with a sweet-wine based sauce. Leszczyński’s guests, when served it, loved it too. Some 30 years after the baba’s creation, the philosopher and encyclopedist Diderot wrote enthusiastically to one of his friends about the baba after he had been invited to dine with the Leszczyńskis. But what really led to a dramatic increase in the cake’s popularity was the marriage between 15-year old Louis XV and Leszczyński’s 22-year old daughter Maria Leszczyńska.

This was definitely not a marriage made in heaven. As readers have seen, the Leszczyńskis were not a great dynasty; a short reign on a modest throne was all Leszczyński père could boast of. At this point they had neither lands nor money; they “depended on the kindness of strangers”, living off a very modest pension. Louis XV, on the other hand, was la crème pâtissière de la crème pâtissière, dynastically speaking, and had lands, properties, and funds to match. The simple fact is, Maria Leszczyńska was the only Catholic princess of marriageable age whom all the opposing factions surrounding the young king had nothing against. And the Regent was in a hurry to marry Louis off; the child had always been sickly and there were real fears that he would die young and childless, precipitating a succession crisis.

So an envoy was dispatched to Wissembourg with the king’s offer of marriage. Readers can imagine that when she read the offer, Maria Leszczyńska fell over herself to accept it, and no doubt Stanisław Leszczyński executed a little Polish jig in his living room upon hearing the news. His fortunes were definitely turning for the better!

Leszczyński fades out of our story at this point. But not to leave readers hanging, wondering what happened to him, let me zip through the rest of his long, long life. As befitted the parents-in-law of the king, who, though, didn’t have two coins of their own to rub together, Leszczyński and his wife were lent one of the king’s many grand residences to live in, in this case the Château de Chambord in the Loire valley, and they were given a considerably bigger pension to live on. He was now a fully-fledged French aristocrat.

About ten years after Maria Leszczyńska married, August II of Poland died. Leszczyński saw his chance and rushed to Poland. But this second attempt to haul himself onto the Polish throne was an even more miserable failure than the first and within two years he was back in France with his tail between his legs. At the time, Louis XV was trying to bring a related war with the Austrian Emperor to a close. After some difficult negotiations, it was agreed, among other things, that the-then Duke of Lorraine (who happened to be married to the future Empress Maria Theresa of Austria) would give up his Duchy (and be given the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in return), that Leszczyński would take over the Duchy of Lorraine and the ducal title, but that the Duchy would revert to the kingdom of France upon his death. Thus did Lorraine become part of France. Leszczyński occupied the ducal throne for nearly 30 years. Since officers of the French King actually ran the Duchy, he spent much of his time beautifying its capital, Nancy, which is indeed a very beautiful city – my wife and I visited it a number of years ago before starting a tour of the French sector of the Western Front. At the exceedingly venerable age of 88, he died – but in a horrible way, alas! He fell asleep near his fire, a cinder fell on his dressing gown, which started to burn fiercely. He died of his burns after several days of agony. RIP Stanisław Leszczyński.

But coming back now to the rum baba. At her wedding, Maria Leszczyńska asked her father if she could take Nicolas Stohrer with her to Versailles. It must have been a wrench, but Leszczyński agreed; he probably didn’t have much else to give her as a dowry. And so Stohrer joined the kitchens of Versailles, helping to serve up meals at glittering court events.

He introduced the court to the baba, but he also invented other pastry dishes in the kitchens of Versailles, some of which are still with us today, notably la bouchée à la reine.

For reasons which are not clear – at least from the records available to me – after five years at Versailles Stohrer handed in his notice (or whatever one did in those days) and set himself up in his own pâtisserie in Paris, at 51 rue Montorgueil, in the 2ème arrondissement.

Amazingly enough, it’s still there! Although no longer owned by the original family, alas …

I have to think that the idea of pre-soaking the baba in the sweet wine sauce must have occurred now if it had not already occurred in the kitchens of Versailles. I can’t see Nicolas Stohrer saying to a customer as he sells them the baba, “take this dried-out cake home and ladle the sauce I’m giving you in this crock over the cake when you serve it. That’ll be 3 francs, 5 sous, please.” I really don’t see that as a sellable proposition. In any event, we can now leave Stohrer and his descendants happily selling babas and other pastries from their shop, and consider the second vital ingredient of our dessert, rum.

Rum is essentially a by-product of the sugar industry. At some point in the refining process, molasses is generated.

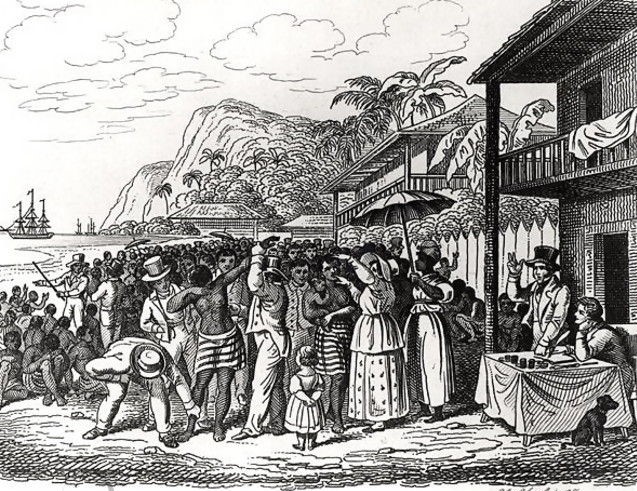

Unless some use can be found for it, it is a waste. From the beginning of the slave-based sugar industry in South America and the Caribbean islands, plantation owners were asking themselves what to do with this molasses.

About 50 years before Leszczyński was born, rum began to be made with it.

Initially, the distillation technology was crude, so the rum produced was very rough: “a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor” is how one document, written in Barbados in 1651, described it. Its main consumers seem to have been slaves, who were allowed to inebriate themselves with it and temporarily forget their terrible lot. With time, its customer base spread to the poor white trash of the colonies, sailors (and of course pirates, as I mentioned earlier), and other riffraff. Sadly, it also became one of the main currencies of exchange in the slave trade. The local slave traders in Africa, the ones who captured the slaves inland and brought them down to the coast, sold their “cargo” to the European slave traders for rum.

Plantation owners of course also eyed the much larger markets in their home countries and tried to export their rum there, or to export their molasses to local rum makers. In the case of France, they came up against the determined resistance of the brandy makers. The making of brandy was a wonderful way for French vintners and others involved in the wine trade to deal with poor quality grapes and soured wine. They already had a good market and were damned if these bloody colonial upstarts and their partners in France were going to cut into their sales. So they launched a strong lobbying effort (what else is new?) and eventually, in 1713 (more or less when Leszczyński became an exile), they persuaded the government to ban the production in France, and sale on the French market, of any alcoholic spirit not made with grapes (which therefore included other spirits like gin, which was also becoming popular).

And that was that for rum in France for nearly 100 years. It was only in 1803 that Napoleon finally allowed rum back onto the French market. By then, distillation techniques had considerably improved and along with them the quality of the rum brought to market. Apart from the population drinking it, I suppose French chefs tinkered with it in their kitchens, to see how it could be used in cooking. Included amongst these tinkerers must have been the Stohrer descendant who now owned that pâtisserie on rue Montorgeuil, or one of his staff. Whoever it was, they had the idea of substituting rum diluted in a syrup of sugar for the sweet-wine mixtures used up to then. The tinkering succeeded and finally the momentous day arrived. In 1835, the new baba au rhum began to be served to the clientele!

The rum baba was of course an immediate success. Other chefs and pâtissiers got into the game.

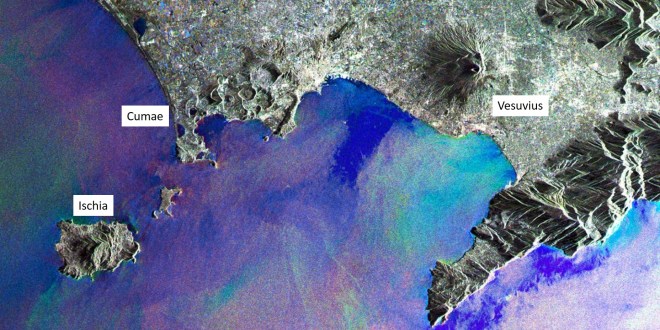

Recipes were included in cook books and knock-offs were created (the most famous being the savarin, which is to all intents and purposes a baba but soaked in a different sauce). It spread to other regions in Europe, one of the most notable being the Bourbon kingdom of Naples. For some reason, il babà (as it was known) became wildly popular there, and over the years it has become an integral part of the food landscape in the Region of Campania, to the point that it has been denominated a Traditional Italian Food Product (Prodotto agroalimentare tradizionale italiano) by the Italian Ministry of Agriculture. Well! That’s pretty cheeky of the Campanians! Talk about cultural appropriation. I wonder what the French think about that? (but then maybe the Poles have something to say about the French taking their baba …) At least the Campanians make it in a different shape (as I noted above) and often use a different liqueur to soak it in, for instance limoncello. But still … In any event, this is the kind of rum baba which I eat in that little café in Santa Margherita, and after tut-tutting about the issue of cultural appropriation, I happily tuck in.

So that’s the story of this wonderful pastry. I urge all my readers to immediately go out and also tuck into a rum baba. As for me, since I happen to be writing this in Vienna where my wife and I have come to spend the month of April, all this research I’ve done has made me hanker after the original cake, the Gugelhopf. I think we should use the time we’re here to have a nice slice of this yummy cake somewhere. I’ll bring this up with my wife – and diet be damned!

Turn that letter upside down, and you have:

Turn that letter upside down, and you have: