Milan, 19 February 2024

My wife and I were recently hiking in the Vienna woods, which at one point required crossing a large open field. We were halfway across it when I was startled to see an emerald green tree on its edge. It was certainly not leaves which were making it green at this time of year. And what was strange was that all the branches were emerald green. Luckily for my sanity, the path we were taking passed close by it, so I was able to inspect the tree more closely. It turned out that all the branches of the tree were thickly covered with a bright green lichen. Foolishly, I didn’t take a photo of the tree, so I’m afraid this photo will have to do.

This vision got me thinking about lichen. They’re very modest beings for the most part, clinging closely to their rock or branch, so I’ve never given them much thought. They give us some gentle splashes of colour on our winter hikes, when all the trees are bare, wildflowers are still asleep, and the skies are grey.

Lichens might be modest beings but they are fascinating. I’m bursting with desire to tell my readers all about them, but I already see my wife shifting around in her seat at the thought of hearing all sorts of biological details that she never wanted to hear about. So, since vibrant colour is what started this post, I’ll just focus on lichens’ connection to dyeing. Which, as readers will see in a minute, will also lead me to write about trade, a topic which I’ve written about many times in these posts.

Let me start by saying that I am really filled with admiration for our remote ancestors. They looked around their ecosystems and tried to find a use for everything that Nature offered them. I, a pampered product of an oversupplied culture, who can get anything I want from anywhere in the world with a mere click of my mouse, would never, ever dream of trying to use lichens as a dye. But our ancestors did, particularly those who lived in ecosystems which did not support a huge amount of biodiversity and so didn’t have that many plants or animals to exploit.

Most of them used lichens as dye sources in the easiest way. They collected them, simmered them in boiling water, waited a while for the lichen to leach out the colour, then added the yarns, simmered, and waited some more (I simplify, but not by much). Modern artisanal dye masters have replicated the processes, with which you can get some quite nice colourings. These photos show some of the lichens used as well as the yarns they have coloured.

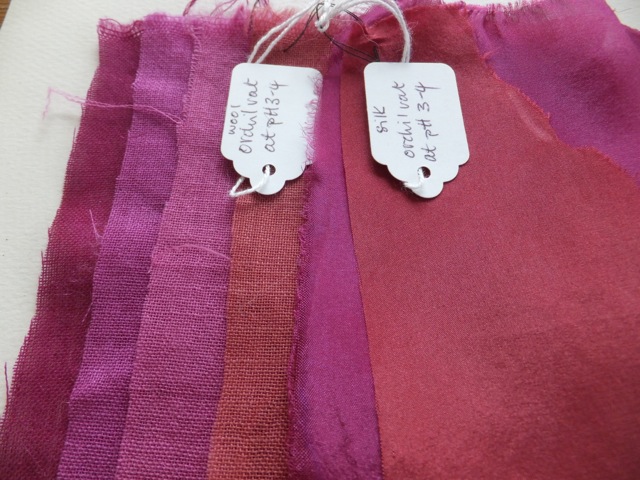

But pride of place in lichen dyeing goes to the various species which give us orchil dyes. These are dyes in the red-mauve to dark purple spectrum – this photo shows the range of colours which modern artisanal masters have managed to tease out of these lichens.

Since they are the source of these lovely colours, I feel I should honour the main species of lichen from which orchil dyes are extracted.

Lasallia pustulata

Ochrolechia tartarea

Evernia prunastri

Roccella tinctoria

Unless some of my readers are passionate lichenologists, I think we can all agree that these lichens are not terribly, terribly beautiful. But by the wonders of biochemistry, they can deliver us lovely dyes. Beauty out of the beasts, as it were.

Anyway, the process to extract orchil dyes is much more complex than the simple boil-it-up-and-dunk-the-yarn-in-it process which I just described. One has to crush the lichen in a solution of ammonia and keep the mix well oxygenated for several weeks. The ammonia slowly reacts with chemicals in the lichens, with the product of these reactions being the purple dye. This effect of ammonia was discovered a long, long time ago, at least in Roman times and very probably before. And in those days the source of the ammonia was … stale urine. Yes, the lichen was steeped in stale urine.

Again, I’m just filled with amazement. How on earth did our ancestors figure this one out? I try imagining scenarios of how someone stumbled across this urine effect by accident – because it had to be by accident. The only thing I can think of is this. Did readers know that in the olden days people used stale urine to “dry clean” their clothes? – ammonia, it seems, is a good stain remover. I came across this … err … interesting procedure when I randomly found myself reading an article about a house which had been excavated in Pompeii. It was a fullery, owned by a fellow called Stephanus. Since the photos of the ruins themselves are not very interesting, I throw in here a reconstruction which some enterprising soul has made.

Readers with good eyes can see the various baths where cloth was fulled. In addition to fulling cloth, Stephanus (or rather his slaves) was dry-cleaning clothes with urine. Given my childish sense of humour (I already see my wife rolling her eyes at this point), I was delighted to read that Stephanus had vases placed in the lane on which the fullery abutted, into which (presumably male) passers-by were invited to pee; I wonder if they ever demanded a payment for their liquid contribution to Stephanus’s business? As for the cleaning itself, this was carried out by some poor bastards whom Stephanus had bought in Pompeii’s slave market. They had to stomp on the urine-soaked clothes for hours. For some reason, another fuller in Pompeii, Veranius Hypsaeus, thought that this operation was a good subject for a fresco in his workshop.

I can’t think of a worse job (well, if I thought hard enough about it, I probably could). But some sources I read brightly informed me that the urine was good for the skin of the feet – a small consolation … And just in case any readers are asking themselves, after the stomping session the clothes were washed in water, to rid them of the smell of urine.

Anyway, my theory is that one day, somewhere, someone used a urine-dry-clean on some clothes which had been dyed with orchil-creating lichens in the traditional way (boil-yarn-and-lichen-and-water-together). For some reason, they left the clothes stewing in the urine for a while – perhaps they were called off to some emergency somewhere and didn’t come back for a week or two – and saw to their astonishment that the clothes had turned purple. It’s a wild guess but it satisfies my fervid imagination.

Orchil really delivers quite a lovely colour. But even more important, that colour is purple. At the time, the best purple dye on the market was Tyrian purple. It was extracted from the gland of a number of shellfish, and it took a huge number of molluscs to extract modest amounts of dye. So readers can understand that it was a very expensive dye. Which meant that only the upper crust could afford it, and eventually in the period of the Roman Empire it was decreed that only the Emperor and his family could wear clothes dyed with Tyrian purple. Unfortunately, the statues we have of Roman Emperors have all lost the colouring they used to have. Luckily, though, we have a coloured picture of one Emperor, Justinian, in the mosaics of the church of San Vitale in Ravenna. As readers can see, his cloak (and even maybe his shoes?) do indeed seem to be purple.

Note, too, the two fellows to Justinian’s right. They were high-level courtiers and were generously allowed to have a broad purple stripe in their cloak. Ah, the complexities of sumptuary regulations …

In this world of strict social hierarchies, orchil allowed society’s wannabes to swan around in purple clothes, aping the manners of their social superiors (it also allowed dyers to use orchil as an initial, or “bottom”, dye, and then use much smaller amounts of the eye-wateringly expensive Tyrian purple to finish the job – and no doubt sell the cloth as 100% dyed with Tyrian purple).

With the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, the use of orchil dyes, along with the knowledge of how to make them, pretty much disappeared in Europe. One place where that was not the case was Florence. In the Middle Ages, the city was a major textiles manufacturing centre. Raw wool, and later raw silk, came into the city from all over Europe and beyond, it was processed into cloth – which meant among other things dyeing the yarn – and then the finished cloth was exported all over Europe and beyond. Here we have a photo of Florentine dyers at work.

Florence’s famous banking system, created by the Medici and other families, was basically created to finance this international trade in textiles. Here we have Florentine bankers working at their banco.

In the 1100s, one of the men working in Florence’s textile industry, a certain Alemanno, rediscovered the techniques of making and using orchil dyes. Quite how he did this is a matter of speculation; business trips to the Levant are invoked, or to the Balearic Islands. Or maybe the techniques hadn’t actually disappeared completely in Italy; he just knew a good business opportunity when he saw one and exploited it effectively. However he did it, Alemanno built a fortune on the purple cloth he made, and his descendants, the Rucellai, became Florentine grandees in the succeeding generations. The family name reflected the original source of their wealth; it is thought to be derived from oricello, the Italian name for the dye (which might in turn be derived from the Italian name for urine, orina). By the 1300s, their wealth and status got them a side chapel in the basilica di Santa Maria Novella. The original frescoes are sadly deteriorated, but there is a rather nice statue of a Madonna with Child by Nino Pisani on the altar.

That Madonna and Child is so charming that I am moved to show a close-up.

By the time the 1400s rolled around, Giovanni Rucellai was the head of the family. While he continued to make money hand over fist from the textile business, like all good Florentines of this golden age he was also a patron of the arts. He paid for the completion of the façade of the Basilica di Santa Maria Novella.

He commissioned the family palazzo in via della Vigna Nuova.

And finally he commissioned his tomb, a small-scale copy of the so-called edicule in the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (any reader interested in comparing the two can do no worse than go to this link).

As befits a Great Man, someone – his heirs, no doubt – commissioned a posthumous portrait of him (note the façade of the Basilica di Santa Maria Novella and his tomb in the background).

All of this great – and expensive – art paid for by urine …

This woodcut shows Florence about ten years after Giovanni died, in 1481.

By then, the world was about to change for the worse for Florence and the Mediterranean world in general. A few years after Giovanni’s death, the Portuguese finally reached the Cape of Good Hope, and then a few years after that they crossed the Indian Ocean and reached India, while Christopher Columbus, in an effort to beat the Portuguese to the Indies, crossed the Atlantic Ocean and stumbled across the Americas. Trade patterns were to change profoundly, with the trade and use of orchil-producing lichens being one modest part of those changes.

Already things were changing when Giovanni was born, in 1403. The year before, a Frenchman by the name of Jean de Béthencourt was conquering the Canary Islands in the name of the King of Spain.

Like all conquistadors, he might have been in it for the glory but he was definitely in it for his own personal gain. One of the things he made his money with was orchil-producing lichens, creating a monopoly, controlled by him of course, in the lichen harvesting business. It was not easy harvesting the lichens. They grew close to the sea, and once the easy bunches had been picked the only source left was lichens growing on the sea cliffs. This photo shows a bunch of Rocella tinctoria hanging over a cliff edge.

To get to these lichen, harvesters had to dangle precariously on ropes over cliff edges, hoping no doubt that sudden strong gusts of wind wouldn’t blow them off, and trying not to look into the abyss below.

As readers can imagine, it was only slaves or other poor sods who did this work.

Jean had the harvested lichen shipped back to his domains in Normandy, where there happened to be a village which specialised in textile manufacturing. With the Canarian lichen, the village’s manufacturers were now able to dye their cloth purple; clearly, the secret – if it ever really was a secret – of using urine to make orchil dye was out. The village grew into a prosperous little town on the back of the dye (and let’s not forget the urine), in recognition of which it is now called Grainville-la-Tinturière, or Grainville-the-Dyer (the village is also twinned with two towns in the Canary Islands in recognition of its historic ties to these islands). As far as I can make out, there seems to be absolutely nothing left of the textile industry in the town, so I shall just throw in a photo of an old postcard of the place.

About 50 years later, in 1456, as the Portuguese crept down the coast of western Africa, they discovered and took over the islands of Cabo Verde. There, too, the same orchil-producing lichens clung to sea cliffs, and there, too, poor bastards hung precariously over the cliff edges to harvest them. In this case, the lichens were shipped back to Lisbon, for onward export to Antwerp and other places. I throw in photos of Lisbon and Antwerp, respectively, in this general period.

As the Portuguese kept creeping down the coast of western Africa, they discovered another source of orchil-producing lichens in Angola, although there – luckily for the harvesters – the lichens grew on trees and were easier to harvest. This photo is from a completely different part of the world, but it gives a good idea of what Angolan harvesters were faced with.

All this meant that for several centuries large quantities of orchil-producing lichens poured into Europe from European colonies. In the meantime, as the science of chemistry progressed, there were improvements to the manufacturing process which led to the production of better dyes. All was going swimmingly until a young English chemist called Henry Perkin kick-started the artificial dye industry by serendipitously creating a completely new dye, which he called mauveine, from coal tar residues. I’ve covered this story in my post on Indigo dye and insert again here the photo I used of this beautiful dye.

That discovery was the death knell of the natural dye industry: artificial dyes were more colour fast, light fast and cheaper. And so making orchil from lichen, and dyeing with lichens more generally, pretty much disappeared. Which actually is probably a good thing. Lichens grow very slowly, so the dye business was decimating them. I never thought I would say this, but for once I’m grateful to chemicals made from fossil fuels. Without them, who knows what would have been the status of lichens today? As it is, they are under threat. Lichens are very sensitive to pollution (one of their modern uses is as indicators of pollution levels), and a good number of species are on the IUCN’s list of endangered species.

That discovery was the death knell of the natural dye industry: artificial dyes were more colour fast, light fast and cheaper. And so making orchil from lichen, and dyeing with lichens more generally, pretty much disappeared. Which actually is probably a good thing. Lichens grow very slowly, so the dye business was decimating them. I never thought I would say this, but for once I’m grateful to chemicals made from fossil fuels. Without them, who knows what would have been the status of lichens today? As it is, they are under threat. Lichens are very sensitive to pollution (one of their modern uses is as indicators of pollution levels), and a good number of species are on the IUCN’s list of endangered species.

So, – ooh, this is hard for me to say – three cheers for the organic chemicals industry!