Sori, Easter Sunday 2025

I suppose every person on this planet will rave about a foodstuff made from the grain which got domesticated in their corner of the planet. I’ve seen Chinese and Japanese go misty-eyed about various rice-based foodstuffs.

I’m sure Central Americans do the same for foodstuffs made with maize.

Or Africans for foodstuffs made with sorghum.

Because my roots are in Europe, where wheat reigns supreme, I go dreamy about foodstuffs made with wheat, a grass that was domesticated in the Middle East. And I go very dreamy about one particular foodstuff made with wheat: bread.

Aaah, that wonderful smell that emanates from local bakeries!

I remember still the delicious scents that wafted out of a bakery in Edinburgh, where I was a student in the early 1970s. It was halfway between my halls of residence and the hall where I was rehearsing plays with the university’s drama society. I would whizz by that bakery on my moped, passing through this cloud of deliciousness.

And the wonderful smell that will greet you as you step into a local bakery’s shop and are confronted by rows of freshly baked loaves!

And the delicious taste as you sink your teeth into a loaf still warm from the oven!

And even when the bread is cold the wonderful taste it will have after you’ve used it to mop up the sauce on your plate.

Or the way it will heighten the taste of a hunk of cheese.

Or of the butter and marmalade you’ve spread onto it.

Mm, yes, bread … (I should note in passing that my heightened appreciation of bread comes from the fact that I eat little of it now – the diet, you know …)

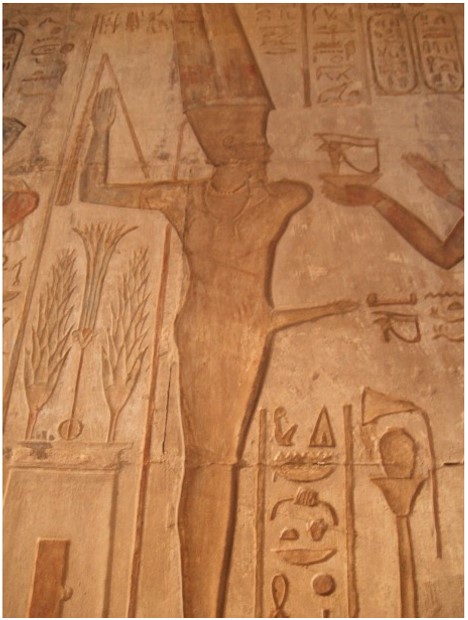

It seems that we have the Ancient Egyptians to thank for these sensory wonders. It is the leavening of bread with yeast that gives bread that very special smell and taste.

And leavening is a discovery the Ancient Egyptians stumbled across. Quite how they did so is a matter of lively debate, at least in certain circles. The theory I most approve of (although no-one is asking for my approval) suggests a serendipitous cross-over from beer making. The making of beer was (and of course still is) another yeast-aided process working on a mash of grains from another grass domesticated in the Middle East, in this case barley. The theory goes that some Ancient Egyptian involved in the making of both unleavened flatbread and beer accidentally splashed some of the beer’s yeast-laden froth (which goes by the delightful name of barm) onto some dough they had prepared. Then for some reason they left the dough to rest for a while (maybe it was evening). When they came back, they saw that the dough had risen. Instead of throwing it away as spoilt, they baked it anyway (maybe supplies of food were limited and they were hungry), and they saw what a marvel resulted.

It can’t have been that simple, there must have been a lot of tinkering after that first leavening of bread, but this story satisfies my fervid imagination. Here, we have small models showing the making of bread, which Ancient Egyptians placed in a tomb, presumably to ensure that the dead person would get to eat bread in the afterlife.

Here we have a similar set of small models from another tomb, showing the brewing of beer.

And here we have some real Ancient Egyptian bread loaves found as grave goods.

I grant you they don’t look terribly edible, but they have been sitting in a grave for several thousands of years after all.

At some point, someone – yet again an Ancient Egyptian, I’m thinking – came up with the idea of keeping back a piece of the leavened dough to inoculate the next batch of unleavened dough. And at some other point, I’m guessing also in Ancient Egypt, leavened dough got contaminated with lactic acid bacteria. Maybe the bacteria were on the hands of the people kneading the dough; they had picked them up touching milk products. Or maybe another pathway came into play. However the contamination occurred, it led to the creation of sourdough; it is these bacteria that give sourdough bread its characteristic sour taste. And so nearly all the pieces were in place for the making of sourdough bread for the next five millennia or so – because until the middle of the 19th Century sourdough bread dominated bread making with wheat.

The last piece of the puzzle was the baking oven. It seems that we have the Ancient Greeks to thank for that. What they came up with must have looked quite similar to the wood-fed ovens which any self-respecting pizzeria will install today.

The cupola shape of these ovens concentrates the heat radiating from the bricks onto the oven’s centre, making it more efficient (and thereby lessening the chore for our ancestors of having to go out to collect wood). And progress in oven-building meant that large ovens could be built, in which multiple loaves could be baked at the same time. Thus was born the profession of the baker (which, among many other things, eventually led centuries later to that delightfully ridiculous nursery rhyme “Rub-a-dub-dub, three maids in a tub, And who do you think were there? The butcher, the baker, the candlestick-maker, And all of them gone to the fair”).

The Ancient Greeks seem also to have taught the uncouth Romans to eat leavened wheat bread. In fairness to the Romans, they weren’t really that different from anyone else in this uncouthness. Originally, they baked flatbread with their grains, or simply ate them in gruel like our Neolithic ancestors had done – but also like many, mostly poor, people have done ever since. I don’t claim to be poor, but the only way I eat oats – another of the grasses domesticated in the Middle East – is as a viscous gruel known to all and sundry as porridge.

And the Italians have what is now a chi-chi dish, zuppa di farro, which originally was just a gruel made with grains of spelt, an early form of wheat which has now all but disappeared.

However, once introduced to the joys of leavened wheat bread, the Romans got into it with a vengeance. And of course evidence of this new enthusiasm of theirs came to light in the ruins of Pompeii, in the form of now burnt loaves of bread abandoned in the town’s bakeries as Mount Vesuvius erupted and the workers ran for their lives.

Perhaps it had already happened elsewhere, but certainly in Rome class reared its ugly head in the matter of bread eating: bread made with the most refined, and so costly, wheat flour, was eaten by the rich, while the poor made do with bread made with poorly sifted whole wheat flour or even a mix of wheat flour and the flour of other grains like barley or oats. That translated into a colour bar: the crumb of the most expensive bread was white while that of the least expensive bread was various shades of brown.

It’s ironic, really, that the rich were eating the nutritionally poorest bread … But at least they were eating other things which could make up for the loss of nutrition in their expensive bread. The poor, on the other hand, had little but bread to eat. Which is why already from the times of the late Republic the Roman governing class was handing out free or subsidised wheat to the poor in Rome, to keep them happy – and politically passive. The Roman poet Juvenal decried this in one of his Satires: “Already long ago, from when we sold our vote to no man, the People abdicated their duties; for the People who once handed out military command, high civil office, legions – everything, now restrains itself and anxiously hopes for just two things: bread and circuses” (it’s a comment that George Orwell updated in his novel 1984 when he described “the Proles”: “Heavy physical work, the care of home and children, petty quarrels with neighbours, films, football, beer and, above all, gambling filled up the horizon of their minds. To keep them in control was not difficult.”)

Fast forward another thousand years or so and we are in Europe’s Middle Ages. The rich were still eating white bread and the poor brown-to-black bread, and bread was still the most important part of the poor’s diet. So nothing much had changed. But if I pause here, it’s because of a very interesting habit we find in rich households regarding tableware. Basically, bread was not just a food, it was also used as a plate. A round piece of, often stale, bread was cut from a large loaf – hence the English name of this tableware, trencher, from the French “trancher”, to cut. The food was ladled onto the trencher, which would absorb any juice or gravy. The illustration below shows trenchers being prepared. It comes from “Les Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry”, a prayer book put together during the first half of the 1400s for the said Duke, who we see sitting at the table.

Once the food had been eaten, the trencher, now softened, was cut up and also eaten.

I find this a wonderful way of eating bread. It’s sad that trenchers began to be made of metal or wood, later to be replaced by the plates we are all familiar with today. The only culture that I know of which uses bread in this way is that of the Ethiopian Highlands, where the food is placed on injera, made with flour from the local grain, teff (although, as this photo shows, nowadays the injera is in turn placed on a plate).

Injera is also used as the utensils to pick up the food.

But back to the bread trencher, where there was a similar relation between rich and poor as there had been in Rome over free supplies of bread. If the harvests had been good, if food in the household was plentiful, if the lady of the house was feeling generous or pious, rather than being eaten the used trencher could instead be given to the poor for them to eat. Or it could be fed to the dogs (which is what the Duc de Berry’s servants seem to be doing in the bottom right-hand corner of the illustration). I suppose when supplies were tight and household ate their own trenchers, the poor were just left to starve.

Bread had now also taken on strong religious overtones in Christian lands, because of the role which bread played in the Last Supper. Many are the paintings of the Last Supper, probably the most famous being the fresco by Leonardo da Vinci. But I won’t show a photo of that fresco. It’s too well known, and anyway you can hardly see anything, it’s in such a bad state of conservation. I’ll throw in a painting by Caravaggio instead, and not of the Last Supper but of the Supper at Emmaus. As recounted in St. Luke’s Gospel (in the King James Version):

And, behold, two of them went that same day [the day of the resurrection] to a village called Emmaus, which was from Jerusalem about threescore furlongs. And they talked together of all these things which had happened. And it came to pass, that, while they communed together and reasoned, Jesus himself drew near, and went with them. But their eyes were holden that they should not know him. … And they drew nigh unto the village, whither they went: and he made as though he would have gone further. But they constrained him, saying, Abide with us: for it is toward evening, and the day is far spent. And he went in to tarry with them. And it came to pass, as he sat at meat with them, he took bread, and blessed it, and brake, and gave to them. And their eyes were opened, and they knew him; and he vanished out of their sight.

You can see the bread loaves Jesus is blessing on the table in front of each of them (I should note in passing that my timing here is excellent, today being Easter Sunday, the day this meeting in Emmaus would have taken place).

The formal theme of Caravaggio’s painting might be religious, but what I see in it is companionship: the Latin roots of the word “companion” are cum and panis, “together with bread”. I find it deeply satisfying that bread was considered not just a food but also a strong binder of friends.

And so we whizz on through the centuries, to stop again at the International Exposition of 1867, which was held in Paris.

It was here that Austria presented the first breads made not with sourdough but with much purer strains of yeast uncontaminated with lactic acid bacteria (later known as baker’s yeast). I will show just one of these breads, the Kaisersemmel, for the simple reason that I eat this from time to time during our sojourns in Vienna.

Many people tried the Austrians’ bread at the Exposition and liked it. Why? Because it tasted “sweet”; it didn’t have that characteristic sour taste of bread made with sourdough. This new, exciting way of making bread, the so-called Vienna Process, caught on. And so, perhaps without anyone really noticing, a fundamental shift started taking place for the peoples in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East who ate leavened wheat bread: they slowly abandoned the sourdough bread which their ancestors had eaten for thousands of years for “sweet” bread. Today, sourdough bread is a niche product.

Was the switch away from sourdough bread a tragedy? I don’t think so. But then, I like sweet bread. I’m quite partial to a Kaisersemmel, for instance, and I will kill for a warm, crusty baguette.

What was definitely a tragedy was the tinkering that went on from the mid-180Os onwards to find ways to make bread faster. “Time is money!” we are told, and never was this aphorism truer than in breadmaking. Making a loaf of sourdough bread takes 24 hours or more from start to finish. Anything to speed this up meant more loaves could be made, and sold, every 24 hours; already the Vienna Process was faster than the traditional method. This tinkering eventually led the British to invent the Chorleywood bread process in 1961. Without going into the technical details, this process can make a loaf of bread from start to finish (sliced and packaged) in about three and a half hours. It results in this hideous kind of product.

A soft, limp crumb, a miserably thin crust, a thing that you don’t need teeth to eat. Dreadful. The only thing it’s good for is to make toast, which probably explains why toast is so popular in the UK.

And so we have followed the rise – literal as well as metaphorical – of leavened wheat bread and its fall into limpness, softness, and general yuckiness. Luckily, it seems that there is a revival of Real Bread, sourdough bread. Rise (again) Sour-dough!