Kyoto, 15 October 2018

As I struggle with jet lag on our annual trip to Kyoto and watch the night sky pale into day, my mind wanders to a previous post that I wrote about stinging nettles. I mentioned there in passing that brambles are also a bitch because of their thorns. And now my tired brain latches onto brambles.

Wicked little bastards those thorns are, capable of slicing with ease through clothing, never mind more delicate tissues like your skin. Look at the damned things!

Talking of which, there was a story doing the rounds of Medieval England which offered an intriguing alternative to the standard narrative of the start of the universal war between Good and Evil. As we all know, that war started with Satan daring to claim that he was the equal of God. Thereupon, in majestic rage, God, through the good offices of his Archangel Michael, threw Satan and his horde out of Heaven – a most dramatic rendition of which scene my wife and I recently came across in Antwerp Cathedral.

The standard story has Satan and his devils all falling into Hell. As John Milton put it so memorably in his opening lines of Paradise Lost

Him the Almighty Power

Hurled headlong flaming from the ethereal sky

With hideous ruin and combustion down

To bottomless perdition, there to dwell

In adamantine chains and penal fire,

Who durst defy the Omnipotent to arms.

In Medieval England instead, they had the poor devils land in bramble bushes, presumably as a pit stop on their way down to their eventual hellish destination. The pain was such that every year, on Michaelmas Day, the feast day of their nemesis the Archangel Michael, the devils would go round all the bramble bushes in England and spit, pee, and fart on the blackberries. I sense that on their satanic rounds, the devils would have looked something like this.

Now, there was actually a moral to this story, to whit: one should not eat blackberries off the bush after Michaelmas Day. A very sensible suggestion, I would say; who would want to pick and eat blackberries after they had been so treated? The precise date when this interdict should come into effect is the subject of some confusion. When the story started on its rounds, England followed the old Julian calendar, in which Michaelmas Day fell on 10th October (in today’s Gregorian calendar). In the Gregorian calendar, though, Michaelmas Day falls on 27th September. The key question is: have the devils continued to follow the Julian calendar or did they switch to the Gregorian calendar like everyone else? While my readers ponder over this conundrum, I should note that, like many fanciful stories from our past, a good scientific reason exists for eschewing blackberry eating after end-September, early-October: the damper autumnal weather encourages the growth of molds on blackberries, grey botrytis cinerea in particular, the eating of which could be perilous for the health of the eater.

It’s typical of devils that they would try to spoil the one fun thing there is about brambles, which is collecting ripe blackberries. Luckily, this is done – or should be done – late-August, early-September, before the devils get around to their nasty business. This summer, when my wife and I were walking the Vienna woods,we got few occasions to pick blackberries; there simply weren’t that many growing along the paths we took. But I still remember my siblings and I going blackberrying some fifty years ago. We would head out to the bramble bushes lining the small country lane which passed by my French grandmother’s house, each of us with a container, slowly moving down the bushes and picking the darkest, juiciest berries. This young girl epitomizes that perilous and sometimes painful search for juicy goodness among the thorns.

She at least managed to come home, with purple fingers (and probably purple mouth), with her finds.

We never seemed to come home with any; eating them on the spot was simply too irresistible, and we would troop home with nothing to show for our work but purple mouths and hands, much to the irritation of our grandmother who had been planning to conserve our blackberries for the winter. My memory fails me at this point but no doubt we would be sent off to the bramble bushes again, with strict orders to bring back the blackberries this time.

Seamus Heaney, the Irish poet and Nobel Laureate for literature, captured well the joys of blackberrying in his poem Blackberry picking, although he speaks too of the heartbreak of his treasured finds going moldy, no doubt with the help of the devils.

Late August, given heavy rain and sun

For a full week, the blackberries would ripen.

At first, just one, a glossy purple clot

Among others, red, green, hard as a knot.

You ate that first one and its flesh was sweet

Like thickened wine: summer’s blood was in it

Leaving stains upon the tongue and lust for

Picking. Then red ones inked up and that hunger

Sent us out with milk cans, pea tins, jam-pots

Where briars scratched and wet grass bleached our boots.

Round hayfields, cornfields and potato-drills

We trekked and picked until the cans were full

Until the tinkling bottom had been covered

With green ones, and on top big dark blobs burned

Like a plate of eyes. Our hands were peppered

With thorn pricks, our palms sticky as Bluebeard’s.

We hoarded the fresh berries in the byre.

But when the bath was filled we found a fur,

A rat-grey fungus, glutting on our cache.

The juice was stinking too. Once off the bush

The fruit fermented, the sweet flesh would turn sour.

I always felt like crying. It wasn’t fair

That all the lovely canfuls smelt of rot.

Each year I hoped they’d keep, knew they would not.

Luckily, by the beginning of last century the terrors of the supernatural had been tamed by science, so that Cicely Mary Barker, in her collection of seasonal flower fairies, was able to transform the nasty devils of the past into this very twee Bramble Fairy.

The fairy was accompanied by an equally twee little poem.

My berries cluster black and thick

For rich and poor alike to pick.

I’ll tear your dress and cling, and tease,

And scratch your hands and arms and knees.

I’ll stain your fingers and your face,

And then I’ll laugh at your disgrace

But when the bramble-jelly’s made

You’ll find your troubles well repaid.

Twee it might be, but the poem’s last lines point us to the next step in the blackberry adventure, namely the eating of them in various yummy forms.

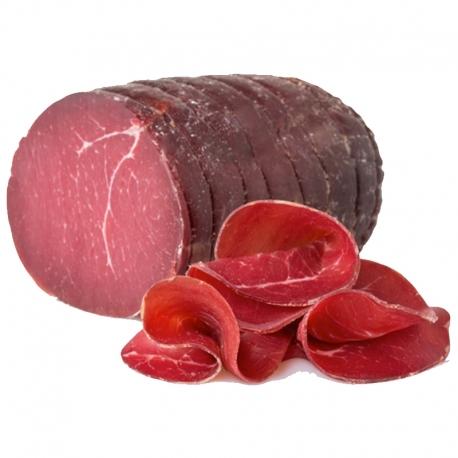

In my opinion, one can do no better than eat blackberries fresh with a dollop or two – or three – of whipped cream.

I’m sure my wife would agree. She once spent a Wimbledon championship selling strawberries and whipped cream to those going in to watch the tennis, and since she no doubt scarfed down a portion of her product when the manager wasn’t looking she will testify to the deliciousness of the cream-berry combination.

The English, however, also swear by the blackberry-apple combination, cooked together in a pie. The ideal is to use windfall apples, so slightly tart, with fully ripe blackberries; the tart-sweet combination which results cannot be beaten, I am assured in article after article.

I’m moved to throw in here a brief recipe for this delicious dish. Start by making the dough for the pie. Put 250g of plain flour into a large mixing bowl with a small pinch of salt. Cut 75g of butter and 75g of lard into small chunks and rub into the flour using thumb and fingertips. Add no more than a couple of tablespoons of cold water. You want a dough that is firm enough to roll but soft enough to demand careful lifting. Set aside in the fridge, covered with a tea towel, for 30 minutes.

In the meantime, preheat the oven to 180°C. Peel, core and quarter 6 Bramley apples, cutting them into thick slices or chunks. Put 20g butter and 100g caster sugar into a saucepan and, when the butter has melted, add the apples. Slowly cook for 15 minutes with a lid on. Then add 150g blackberries, stir and cook for 5 more minutes with the lid off.

Meanwhile, remove the pastry from the fridge. Cut the pastry in half and roll one of the pieces out until it’s just under 1cm thick. Butter a shallow 25cm pie dish and line with the pastry, trimming off any excess round the edges.

Tip the cooled apples and blackberries into a sieve, reserving all the juices, then put the fruit into the lined pie dish, mounding it in the middle. Spoon over half the reserved juices. Roll out the second piece of pastry and lay it over the top of the pie. Trim the edges as before and crimp them together with your fingers. Make a couple of slashes in the top of the pastry. Place the pie on the bottom of the preheated oven for 55 to 60 minutes, until golden brown and crisp.

In these troubled times of Brexit, when there are those Little Englanders who would question the UK’s belonging to a wider European culture, I feel that I should point out that this pie is not uniquely English. Already some 450-500 years ago, the Dutch painter Willem Heda lovingly painted a half-eaten apple and blackberry pie (unfortunately, my wife and I did not see this particular painting during our trip this summer to the Netherlands).

I feel I must include here a variation on the pie theme, the blackberry-apple crumble, only because my Aunt Frances used to make the most sublime crumble, whose magnificence I remember even now, more than half a century after the fact.

Once again, pre-heat the oven to 180°C. To make the crumble, tip 120g plain flour and 60g caster sugar into a large bowl. Cut 60g unsalted butter into chunks, then rub into the flour using your thumb and fingertips to make a light breadcrumb texture. Do not overwork it or the crumble will become heavy. Sprinkle the mixture evenly over a baking sheet and bake for 15 mins or until lightly coloured. Meanwhile, prepare and cook the apple-blackberry compote as before. Spoon the warm fruit into an ovenproof gratin dish, top with the crumble mix, then reheat in the oven for 5-10 mins.

Since the Bramble Fairy speaks about bramble jelly, and since something like it was the reason my grandmother sent us out to collect blackberries, I feel I should mention this preserve too.

Staying with the apple-blackberry combination, I give here a recipe which contains apples. But the purpose of the apples is different. It is to naturally add pectin to the mix so as to make a firmer jelly.

Put 2 cooking apples, washed, cored, and diced, and 450ml of water in a large saucepan. Bring to the boil, then simmer over a low heat for 20-25 minutes or until the fruit is completely soft. Tip the soft fruit and juice into a jelly bag (which has been previously boiled to sterilize) and leave to drip for 8 hours or until all the juice has been released. Prepare the jam jars by washing in hot soapy water and leaving to dry and warm in a cool oven for 10-15 minutes. Measure the juice. For every 600ml weigh out 450g sugar. Put the juice and sugar back into the clean pan, heat over a low heat until all the sugar has dissolved. Bring to the boil and simmer for 10-15 minutes or until setting point is reached. Skim away any scum from the top of the jelly and fill the jam jars to the brim. Cover, seal and label. Store in a cool, dark place until required.

It goes without saying that the juice of blackberries can be drunk too, in many forms. I will only mention one of these, blackberry wine, and only because I once made the closely related elderberry wine at school, with a couple of friends. More on this later. Let me focus first on the making of blackberry wine. If any of my readers want to try this, they can use the following recipe which I lifted from Wikihow.

To make 6 bottles of wine:

– 4½-6 lbs of fresh blackberries

– 2½ lbs of sugar

– 7 pints water

– 1 package yeast (red wine yeast is recommended)

Crush the berries by hand in a sterile plastic bucket. Pour in 2 pints of cooled distilled water and mix well. Leave the mixture for two hours.

Boil ⅓ of the sugar with 3 pints water for one minute. Allow the syrup to cool. Add the yeast to 4 oz of warm (not boiling) water and let it stand for 10 minutes. Pour the cooled syrup into the berries. Add the yeast. Make sure the mixture has properly cooled, as a hot temperature will kill the yeast. Cover the bucket with a clean cloth and leave in a warm place for seven days.

Strain the pulp through fine muslin or another fine straining device, wringing the material dry. Pour the strained liquid into a gallon jug. Boil a second ⅓ of the sugar in 1 pint water. Allow it to cool before adding it to the jug. Plug the top of jug with cotton wool and stretch a pin-pricked balloon to the neck. This allows CO2 to escape and protects the wine from oxidization and outside contamination (the demijohn in the photo has a much more sophisticated stopper for the same purpose).

Let the wine sit for ten days. Siphon or rack the wine to a container. Sterilize the jug, then return the wine. Boil the remaining ⅓ of the sugar in the last pint of water, allowing to cool before adding to the wine. Plug the jug with the cotton wool and balloon and leave until the wine has stopped fermenting. The wine will stop bubbling when fermentation has stopped.

Siphon the wine as before. Sterilize the wine bottles and add a funnel. Pour the wine into the bottles, filling each bottle to the neck. Cork and store the bottles.

Cheers!

Reading this, I realize why our attempt at making elderberry wine fifty years ago was such a miserable failure. Readers should first understand that what we were doing – making an alcoholic drink – was strictly prohibited, so we were exceedingly furtive in everything we did. With this premise, let me describe the steps we went through. As I recall, we mashed the elderberries with water and yeast, a packet of which we bought down in the village (Lord knows what the lady behind the counter thought we were doing with the yeast; she was too polite to ask). I don’t remember parking the resulting liquid somewhere warm to ferment, we simply put the mash into (unsterilized) bottles that we purloined from somewhere; did we even strain out the solids? I have my doubts. Our most pressing problem was where to hide the bottles while the juice was fermenting into (we dreamed) wine. Our first idea was to put them in a sack and haul this to the top of a leafy tree where it was well hidden. But we had forgotten that trees lose their leaves in Autumn. So readers can imagine our horror when our sack became increasingly visible – from the Housemaster’s room, no less – as the leaves dropped off. We hastily brought the sack down one evening and buried it in a little wood behind our House. Later, when we reckoned the fermentation must be over, we furtively dug up the sack. Two out of the three bottles had exploded. We took the remaining bottle into the toilet and drank it. Of course, we pretended to be drunk, although in truth the potion we had concocted had little if any effect on us; the levels of alcohol in it must have been miserably low. And the taste was distinctly blah. I’ve had it in for elderberries ever since.

Unsurprisingly, we humans have been eating blackberries for thousands of years. Swiss archaeologists have discovered the presence of blackberries in a site 5,000 years old while the Haralskaer woman was found to have eaten blackberries before she was ceremonially strangled and dumped in a Danish peat bog 2,500 years ago.

As usual, our ancestors not only ate the fruit but believed that the rest of the plant had medicinal properties of one form or another. As a son of the scientific revolution, I have grave doubts about the purported therapeutic value of berries (ripe or unripe), leaves, and flowers, when no rigorous scientific testing has ever been carried out to support the claims. However, there is one medicinal property which I will report, simply because two widely divergent sources, who could not possibly have known of each other’s existence, mention it. The first is a book of herbal remedies, the Juliana Anicia Codex, prepared in the early 6th Century in Constantinople by the Greek Dioscorides, and which is now – through the twists and turns of fate that make up history – lodged in Austria’s National Library in Vienna. This is the page in the book dedicated to the bramble.

The text relates, among other things: “The leaves are chewed to strengthen the gums ”. For their part, the Cherokee Indians in North America would chew on fresh bramble leaves to treat bleeding gums. The same claim by Byzantine Greeks and Cherokee Indians? That seems too much to be a mere coincidence. When the world has gone to hell in a handbasket because we were not able to control our emissions of greenhouse gases, and when my gums begin to bleed because there will be no more dentists to go to for my annual check-ups, I will remember this claim and chew on bramble leaves.

On that pessimistic note, I will take my leave of my readers with a poem by the Chinese poet Li Qingzhao. She lived through a period of societal breakdown, when the Song Dynasty was defeated by the nomadic Jurchens in the early 12th Century and retreated southward to create an impoverished rump of its empire, known to us as the Southern Song, around the city of Hangzhou. Li Qingzhao reflected on this period of decline and decay in her later poems. I choose this particular poem, her Tz’u Song No. 1, because it happens to mention blackberry flowers and blackberry wine.

Fragrant grass beside the pond

green shade over the hall

a clear cold comes through

the window curtains

crescent moon beyond the golden bars

and a flute sounds

as if someone were coming

but alone on my mat with a cup

gazing sadly into nothingness

I want to call back

the blackberry flowers

that have fallen

though pear blossoms remain

for in that distant year

I came to love their fresh fragrance

scenting my sleeve

as we culled petals over the fire

when as far as the eye could see

were dragon boats on the river

graceful horses and gay carts

when I did not fear the mad winds

and violent rain

as we drank to good fortune

with warm blackberry wine

now I cannot conceive

how to retrieve that time.

_______________________

Blackberry thorns: http://iuniana.hangdrum.info

Frans Floris, “Fall of the Rebel Angels”: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Fall_of_rebel_Angels_(Frans_Floris)_September_2015-1a.jpg

Devil: https://www.etsy.com/sg-en/listing/517991225/the-devil-ceramic-decal-devil-ceramic

Blackberry fairy: https://flowerfairies.com/the-blackberry-fairy/

Blackberry picking: https://spiralspun.com/2013/10/29/blackberry-picking-one-of-lifes-simple-pleasures/

Jug of blackberries: https://spiralspun.com/2013/10/29/blackberry-picking-one-of-lifes-simple-pleasures/

Blackberries with whipped cream: https://depositphotos.com/80606340/stock-photo-fresh-blackberries-with-whipped-cream.html

Apple and blackberry pie: https://www.thespruceeats.com/british-apple-and-blackberry-pie-recipe-434894

Willem Claesz. Heda, Still Life with a Fruit Pie: https://www.masterart.com/artworks/502/willem-heda-still-life-with-a-blackberry-pie

Apple and blackberry crumble: https://www.taste.com.au/recipes/apple-blackberry-crumble/837e5613-3708-42f2-8835-dcd9dd3b3876

Blackberry jelly: https://www.bbc.com/food/recipes/bramblejelly_13698

Demijohn of blackberry wine: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/371476669246000245/

Bottled blackberry wine: http://justintadlock.com/archives/2018/01/27/bottled-blackberry-wine

Glass of blackberry wine: https://www.pinterest.pt/pin/573294227542445354/

Haraldskaer woman: http://legendsandlore.blogspot.com/2006/01/haraldskaer-woman.html