Vienna, 30th July 2023

It was an exploded view of a hamburger which I saw recently at a fast food joint while my wife was getting coffees that set me off. The hamburger was separated, accordion-like, so that each of its ingredients was clearly separated from the others while still being part of a recognisable whole. I just managed to take a photo before the subway arrived – a bit wonky, given I was in a hurry.

This exploded hamburger got me asking myself: “How many of the ingredients in that most American, most iconic, of hamburgers, McDonald’s Big Mac, originated in the US?”. Here is a photo of this deliciously yummy – but frightfully-bad-for-you – fast food offering.

Of course, I’m sure that many if not most of the ingredients which are used in a Big Mac sold in the US are grown or raised there, but how many of them originally came from the North American continent in the distant past?

The answer, dear reader, is none. Not a single one of its main ingredients, or even of its not-so-main ingredients, originated in the North American continent.

In case any readers don’t believe me, here is a list of the Big Mac’s ingredients, courtesy of MacDonald’s website. We are informed that the Big Mac contains:

-

- two beef patties

- pasteurised process American cheese

- shredded lettuce

- minced onions

- pickle slices

- Big Mac sauce

- three slices of sesame-seed bun

Now let’s see where all the foodstuffs behind these ingredients came from. Let’s start with the beef patties, which surely – with the bread – are the heart of a hamburger; the rest are just add-ons.

The cattle which give us the beef patties were originally domesticated from the wild auroch in about 8,500 BCE, somewhere in the Levant and/or central Anatolia and/or Western Iran (aurochs were domesticated once more, possibly twice more, but the cattle MacDonald’s use almost certainly come from that first domestication event). Aurochs were hunted by our Cro-Magnon ancestors, who left us beautiful paintings of these beasts on the walls of caves like Lascaux.

Alas, they are now extinct, the last one having perished in 1627 in the Jaktorów forest in Poland. All that’s left are some miserable skeletons in museums.

There is a minor, but important ingredient that goes along with the patties, and that is black pepper, which MacDonald’s tells us that their patties are grilled with. The black pepper vine is native to South and South-East Asia and it was there that farmers began to intentionally grow the vine to harvest its crop. We see it here in the wild.

And here we see the peppers hanging on the vine.

The domestication of cattle not only led to the patties but also to dairy products, so it’s fitting to deal next with the “pasteurised process American cheese” in the Big Mac.

I don’t know what readers think, but these slices of stuff don’t look like any cheese I’ve ever seen. Nevertheless, McDonald’s assures us that it is actually 60% cheese – 51% cheddar and 9% other, unspecified, cheese. The remaining 40% includes various other milk-related products – whey powder, butter, milk protein – as well as water and of course various other crap – sorry, food additives – which act as emulsifiers, anti-caking agents, colourants, and Lord knows what else. We’ll ignore all those horrors and focus on the milk-related products.

It makes sense to think that the domestication of aurochs – and of the other two main dairy animals, sheep and goats – pretty quickly led our ancestors to exploit their milk as well as their meat. And in fact, our earliest archaeological evidence of dairying is lipid residue in prehistoric pottery found in Southwest Asia, dated to the seventh millennium BCE. This all suggests that once again the Middle East – broadly defined – was the point of origin of all the cow milk-related products – cheese, whey, butter – in that slice of pasteurized process American cheese. To celebrate all these milk products, I throw in various photos. the first is of a farmer’s wife milking a cow. I remember this from my childhood. My French grandmother would send me to the nearby farm with a small jug, which the lady would fill, milking her cow in front of me in the barn.

The second photo is of something which I’ve never seen, even on an industrial scale, the making of butter in a butter churn.

The third photo celebrates Little Miss Muffet who was eating curds and whey, with curds being the first step in cheese production, before that pesky spider frightened her away.

Let’s now turn to the shredded lettuce.

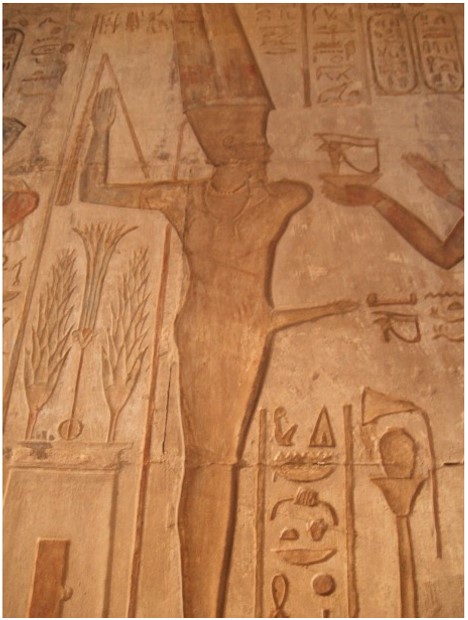

McDonald’s tells us it uses iceberg lettuce, but for our purposes it doesn’t matter which variety of lettuce they use because all lettuces descend from the same domestication event. We have the ancient Egyptians to thank for first cultivating the lettuce, with the earliest evidence of its cultivation being from about 2700 BCE. Here is a photo of what the first domesticated lettuces looked like (those plants to the left).

I should hastily explain that apart from eating lettuce, the ancient Egyptians believed the plant to be the sacred to Min, the god of reproduction; I don’t think I need to point him out in the photo. The Egyptians thought lettuce helped the god “perform the sexual act untiringly”, because it stood straight and tall and when cut it oozed a semen-like latex. (I wonder if some echo of these beliefs explains why my wife’s maternal grandfather liked to eat a head of lettuce every day?) In any event, as readers can see the ancient lettuce looked quite different from modern lettuces; we have to thank the patient work of countless generations of farmers for that.

We can now turn our attention to the minced onion.

There is no general agreement about where the onion was first domesticated. Many experts think the domestication event took place in Central Asia, but there are partisans for Iran and western Pakistan. As to when it was domesticated, traces of onions have been recovered from Bronze Age settlements in China dated to 5000 BCE, so domestication must have occurred quite a good deal earlier. I throw in a photo of a wild onion plant, although not the plant which was domesticated; it’s not clear to experts which onion plant was.

It seems appropriate to stay with the vegetables in the Big Mac, so let’s turn now to the pickle slices.

The primary raw material in this case is of course cucumbers – the smaller version rather than the larger version.

The wild plant is native to the Himalayan foothills, with a range that stretches from western India all the way to China, but it was the Indians who domesticated it, by at least 3000 BCE. As an example of the Himalayan foothills, I throw in here a picture of a rope bridge across the Alaknanda River near Srinagar in Kashmir, from the late 18th/early 19th Centuries.

This picture is actually a plate in a six-volume book entitled Oriental Scenery, but I have an aquarelle of exactly the same scene, which I picked up at the Dorotheum auction house for a pittance.

But back to the topic in hand. Of course, it’s not just cucumbers we need here, we also need vinegar to pickle them (pickling is also possible with salt and other things, but MacDonald’s lists vinegar as one of the ingredients for its pickle slices). The first documented evidence of the deliberate making of vinegar (rather than an alcoholic beverage spoiling and turning into vinegar) was in Mesopotamia, in about 3000 BCE. Not surprisingly, the earliest evidence of pickling in vinegar has also been found in Mesopotamia, from around 2400 BCE, with archaeological evidence of cucumbers in particular being pickled there from 2030 BCE.

We now have to tackle the special Big Mac sauce, which I think readers will agree – or at least those who will admit to having eaten a Big Mac – is the clou of this fast food offering. Let’s be frank, without that yummy, finger-lickin’ly-delicious sauce the Big Mac would be rather bland.

Of course, MacDonald’s keeps the precise recipe a closely guarded secret, a commercial tactic which I’ve commented on before, and their bald list of ingredients doesn’t really tell you how exactly the sauce is put together. Luckily, however, litres of electronic ink have been spilled all over the internet detailing people’s attempts to recreate the sauce, and these give us the basic “design” of the sauce. It is just a mix of mayonnaise and “sweet relish”.

The mayo part gives us a number of new ingredients to consider: egg yolks, oil, and mustard (as part of a “spice mix”). Vinegar is of course also required to make mayonnaise, but we have already covered that. As for the sweet relish part, that’s just our friend pickled cucumber with sugar added. So all we need to consider is the sugar which is added as sweetener. (In all this, I am ignoring the evil food additives which MacDonald’s throws into the mix, to emulsify and thicken and make even sweeter and preserve and firm up and, and, and …).

Egg yolks is really the story of the domestication of the chicken; this is one case where the chicken comes before the egg. The chicken was domesticated from the red junglefowl in about 6,000 BCE in Southeast Asia. There are still wild red junglefowl padding through the jungle undergrowth. They are magnificent creatures – at least, the males are.

My wife and I were lucky enough to see junglefowls, or chickens that were still quite junglefowlish, in Indonesia. Really lovely creatures.

Interestingly enough, the red junglefowl may have originally been domesticated not for food but for cockfighting. Here is a Roman mosaic of a cock fight, when the practice was already centuries old.

It was only later that chickens became a major source of eggs and later still a major source of meat – the earliest archaeological evidence of large-scale eating of chickens is only from about 400 BCE.

As for the oil which goes into the mayonnaise, recipes in different parts of MacDonald’s website list soybean oil in one place and rapeseed oil in another. I presume this simply means that the choice of oil depends on availability. Let’s start with soybean oil. Given the popularity of soy products in East Asia, I’m sure it will come as no surprise to readers to learn that it was in that part of the world that soybean plants were first domesticated. In fact, it seems to have been domesticated several times. The oldest domestication event was in China, some time between 7000 and 6000 BCE, with another domestication event in Japan some 2000 years later and yet another in Korea some 6000 years later. Here we have modern Chinese farmers bringing in the soybean harvest.

For rapeseed, on the other hand, the honour for first domestication seems to go to India, which is where the earliest evidence of domesticated rapeseed, dated at 2000 BCE, has been found. That being said, it should be pointed out that it was only very, very recently – in the 1970s, in Manitoba, Canada – that a cultivar of rapeseed was created that produced edible oil, which is really what interests us for the Big Mac special sauce. Before that, a chemical naturally present in rapeseed oil gave it a disagreeable taste, so it was only used for such things as oil for lamps. Which explains why it’s only in the last 50-some years that the European countryside has become covered with acre after monotonous acre of yellow-flowered rapeseed being grown to produce edible oil.

The mustard-spice mix is such a small part of the overall Big Mac that it doesn’t get a picture om MacDonald’s website. But mustard is an interesting plant, which I’ve written about in an earlier post. It’s a complicated plant. For starters, focusing for a minute on the seeds – which is what we are interested in from a condiments point of view – there are three types: black, brown and white seeds. Each come from different plants with their individual domestication histories.

The first two are the most common, and of these two MacDonald’s almost certainly uses brown seeds, for the simple reason that a cultivar of the plant has been developed where the seed pods don’t shatter when harvested, whereas such a cultivar doesn’t exist for black mustard (having seed pods which don’t shatter during harvesting is incredibly important; the last thing you need when you harvest a seed crop is to have the pods shatter and the precious seeds scatter all over the ground). So here is the plant Brassica juncea which was domesticated to give us brown seeds.

But it was also separately domesticated for its edible root, leaves, and stem, and it has been difficult for scientists to distinguish between these various domestication events. Nevertheless, the latest analyses suggest that the plant was first domesticated for its seeds in what is now Afghanistan, in about 2000 BCE.

All that being said, the critical point about mustard – what makes mustard powder become the fiery condiment we know today – is its mixing with liquids, often nowadays vinegar. Although the vinegar in the mayonnaise is playing another role, I have to assume that when the powdered mustard seeds are added to the mix, their fire is unleashed (my earlier post explains the biochemistry). The Ancient Romans were the first to come up with this innovation – “mustard” comes, via the French, from the Latin “mustum ardens”, fiery must. It seems that the Romans liked to use must as the liquid to set mustard seeds off.

Which brings us to the sugar in the sweet relish part of the Big Mac sauce. Here, too, there is a complication, because MacDonald’s could easily be sourcing their sugar from two quite different sources: sugar extracted from sugar cane or from sugar beet. Let’s start with sugar cane, the oldest of the two sources. Modern sugar cane is the result of an initial domestication event and then a key hybridisation event. The initial domestication event took place in New Guinea, in about 4000 BCE, when the Papuans domesticated the wild grass Saccharum robustum to create S. officinarum. This domesticate travelled west to Island Southeast Asia (mostly what we call today Indonesia), where, at some point, it hybridised with S. spontaneum, another species of the family. Without this hybridisation, sugar cane would not have become the global crop it is today because S. spontaneum gave the resultant cross high tolerance to environmental stress. We have here a rather pretty botanical painting of S. officinarum, much nicer than photos of fields of sugar cane, which are really monotonous.

One further important technical innovation took place in about 350 CE, in India. Until then, people had drunk the juice squeezed from the cane. It was the Indians who first figured out how to turn the juice into the granulated sugar we know and use today. A useless factoid: the word “sugar” derives from the Sanskrit word sharkara, which means “gravel” or “sand”.

How about sugar from beetroot? This has a much, much shorter history than any of the other ingredients considered up to now, with the exception of the edible form of rapeseed oil. It wasn’t until the 18th Century, in Prussia, that a cultivar of the beetroot was developed which contained high enough levels of sugar to make it competitive with sugar cane. This is a rare case where we know the names of the people who were responsible. It was the Prussian scientists Franz Karl Achard and Moritz Baron von Koppy and his son, although the initial impulse – and funds – for their efforts came from Frederick the Great, who wanted to develop a local source of sugar. That being said, the French really pushed the development of sugar beet. It started with Napoleon, who was looking for another source of sugar to take the place of the Caribbean cane sugar whose import into France was being blockaded by the filthy English. Here is a French sugar beet factory from 1843.

We can now turn to the final element of the Big Mac, the three slices of sesame-seed bun.

This is what sort of holds all the other ingredients together (I say sort of, because my experience with Big Macs is that, well lubricated by the Big Mac sauce, the other ingredients tend to slide out from between the bread slices onto the table or, worse, onto my trousers). Going back once again to the list of ingredients on MacDonald’s website, I can see that there are only two primary ingredients in the bun that I need to discuss, the wheat flour and the sesame seeds sprinkled over the top bun. I’ve already covered the other major ingredients, sugar and oil (soybean or rapeseed). (And of course I am once again ignoring all the filthy food additives which are also part of the recipe. I’ve also decided not to go on a rant about the fact that MacDonald’s uses wheat flour fortified with iron and various B vitamins. I will limit myself to say that if they used whole grain flour, all these micro-nutrients would still be in the flour and there would be no need for the flour producers to add them back in).

Although there are a number of different wheats, it’s almost certain that MacDonald’s uses common wheat, Triticum aestivum, to make their buns; this variety makes up about 95% of wheat produced worldwide; the remaining 5% is durum wheat. The origin story of common wheat is similar to that of cane sugar: an initial domestication, in this case of emmer wheat, followed by a hybridisation with wild goat-grass. Emmer wheat was first domesticated in about 10,000 BCE, in what is now southern Turkey, while archaeological evidence from the same general area suggests that its hybridisation with wild goat-grass had already occurred by about 6500 BCE. Here is a photo of wild emmer wheat in its natural environment.

Which brings us to our final ingredient, the sesame seeds sprinkled on top of the bun. The plant on which the seeds grow, Sesamum indicum, originated – as its scientific name indicates – in India. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Indians had domesticated the plant by at least 3500 BCE. This photo shows another side of the plant, its rather lovely flower.

So, like I said at the beginning, not one of the ingredients in that uber-American fast food product the Big Mac originated in North America. Which in a way is strange; I read somewhere that approximately 60% of the food consumed worldwide originated from the Americas. I’m guessing that the massive consumption of maize around the world is primarily responsible for that, with potatoes, sweet potatoes, and tomatoes adding to it. But actually, given the history of North America’s colonisation, it is not so strange.

When we step back and look at where all the Big Mac’s ingredients originated, we can see that the great majority of them came from somewhere between the Middle East and Southwest Asia. Over the millennia, the domesticates moved west into Europe (as well into East Asia and Africa, but it’s the movement into Europe which interests us). My sense – perhaps completely unfounded – is that much of this movement came about peacefully, in many possible ways. A farmer got hold of seeds from their neighbour and tried them out, and then other farmers got seeds from that farmer, and so on, spreading seeds in a sort of ripple effect. Or maybe seeds moved with marriages, with women (probably) bringing seeds from their village. Or maybe people picked up new seeds as they travelled to foreign places for trade or other reasons. Maybe new foodstuffs were actually part of trades: “I give you this fine bronze dagger for seeds of that new foodstuff you have there”. Or maybe foodstuffs were gifts between rulers.

No doubt some movement of foodstuffs also came about through aggression. For instance, there could have been forced displacement of one group of people by another carrying their own seeds. This could have been the case when farming people, bringing their foodstuffs, cereals especially, migrated into Europe from Anatolia and replaced the original hunter-gathering people there – although I’ve also read that the hunter-gatherers simply got absorbed into the new farming societies; I’ve also recently read that perhaps there were few if any hunter-gatherers left to replace because they had been wiped out by bubonic plague – a bit like what happened in the Americas. Or maybe new foodstuffs were part of the booty of conquest. If you conquered a new land, you checked out its foodstuffs and brought back what you thought could be used by your people. I can imagine that the Ancient Egyptians’ wars against the Assyrians could have been one way new foodstuffs entered Egypt. And it is often suggested that Alexander the Great’s armies came back from the East with new foodstuffs in their baggage (I mentioned something similar in my recent post on Tabasco peppers, suggesting that American soldiers fighting in Mexico in the Mexican-American War of 1846-48 could have brought seeds of the Tabasco pepper back to the US).

However it happened, by the time European colonists arrived in North America, all the foodstuffs in the Big Mac were part of their agricultural baggage. Quite naturally, they brought their foodstuffs with them as well as their culinary habits. Initially, when the colonists were few and the balance of forces more even between them and the Native Americans, they were happy to try Native American food – isn’t that what Thanksgiving celebrates? But as more and more colonists arrived, they pushed aside the Native Americans and created a “little Europe”, mostly eating the foods of their homelands. It was in this context that the Big Mac was born. Basically, it was a European dish created in the USA by Americans of European heritage.

It’s a pity, I think, that not more of the foodstuffs Native Americans were eating have stayed in the American diet. Apart from anything else, it could help make American food systems more resilient in the face of climate change, since the native foodstuffs belong to the American ecosystem while the imported foodstuffs do not. But it would require a lot of work. Many of the foods that Native Americans were eating were wild – there was little farming in North America when the Europeans started arriving, the Native Americans were primarily hunter-gatherers – so the whole process of domesticating them would have to be undertaken. With modern, scientific methods, maybe that could be done faster than in the past. But it would still require time, effort – and money. Who would spend the money? But still, if you take a spin through the internet, you find a lot of people trying to recover Native American foods and dishes. How about merging the old with the new? Could we redesign the Big Mac to make it only with North American ingredients, I wonder?