Vienna, 24 February 2026

A few weeks ago, when we were down at the seaside, my wife and I went to the Palazzo Reale in Genova to see an exhibition on St. George. The excuse for the exhibition was that he is one of the patron saints of Genova (as he is of England and many other cities, regions, and countries). I’m sure many of my readers are familiar with the most famous story about St. George, his killing of a dragon to save a young woman. But just in case, I cite here the story as told in the Legenda Aurea, a compendium of hagiographies of saints and martyrs, written by one Jacobus de Voragine (who, it so happens, was a bishop of Genova). The original was written in Latin, so I give the 1483 English translation by William Caxton (I’ve cut it a little to focus on the essentials):

By [the city of Silene, in the province of Libya] was a pond like a lake, wherein was a dragon which poisoned all the country. … And when it came nigh the city it poisoned the people with its breath, and therefore the people of the city gave to it every day two sheep for to feed it, because it should do no harm to the people. And when the sheep failed … then was an ordinance made in the town that there should be taken the children and young people of them of the town by lot, and every each one as it fell, were he gentle or poor, should be delivered when the lot fell on him or her.

So it happed that [after] many of them of the town were delivered, … the lot fell upon the king’s daughter, whereof the king … began to weep, and said to his daughter: “Now shall I never see thine espousals.” … Then did the king array his daughter like as she should be wedded, and embraced her, kissed her and gave her his benediction, and after led her to the place where the dragon was.

When she was there St. George passed by, and when he saw the lady he asked her what she made there and … she said to him how she was delivered to the dragon. … Thus as they spake together the dragon appeared and came running to them, and St. George was upon his horse, and drew out his sword and garnished himself with the sign of the cross, and rode hardily against the dragon which came towards him, and smote it with his spear and hurt it sore and threw it to the ground.

And after he said to the maid “Deliver to me your girdle, and bind it about the neck of the dragon and be not afeard.” When she had done so the dragon followed her as it had been a meek beast and debonair. Then she led it into the city, and the people fled by mountains and valleys, and said: “Alas! alas! we shall be all dead.” Then St. George said to them: “Doubt ye no thing, without more, believe ye in God, Jesu Christ, and do ye to be baptized and I shall slay the dragon.”

Then the king was baptized and all his people, and St. George slew the dragon and smote off its head, and commanded that it should be thrown in the fields, and they took four carts with oxen that drew it out of the city.

The story gave great opportunities to numerous painters to strut their stuff. Here is a selection of paintings.

This is probably one of the more famous paintings of the subject, by Paolo Uccello. It has St. George spearing the dragon, but unlike other paintings of the genre is has also included the scene of the young princess’s girdle being tied around the dragon’s neck.

This next painting is by Carpaccio. Notice the remains of previous victims littering the ground. This detail was quite popular.

From the same period but more refined, a painting by Raphael.

To show that it wasn’t just Italian artists who painted the subject, here’s one from the other side of the Alps, by the Flemish artist Rogier van der Weyden

And here is a woodcut by Albrecht Dürer.

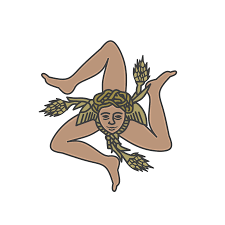

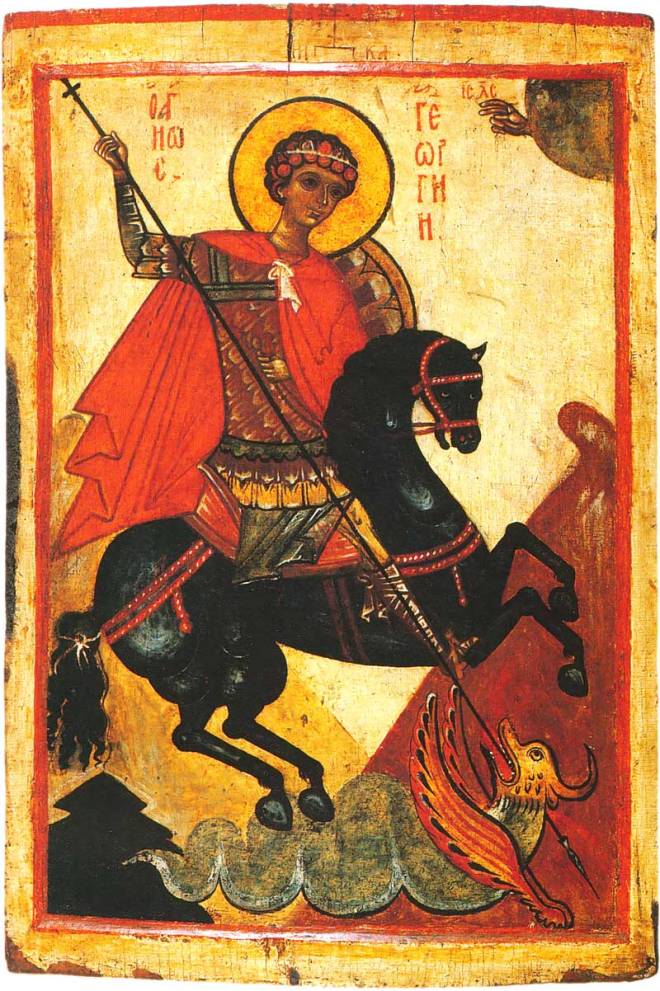

And just to show that St. George was equally popular in Orthodox Christianity, here is a Russian icon of St. George killing the dragon. Here, the damsel in distress has been eliminated; instead, we have the hand of God blessing St. George.

Quite honestly, the dragon is the most interesting part of the story; St. George and the princess are very virtuous and therefore boring. So let’s focus on the dragon. It’s quite obvious from the story that the inhabitants of Medieval Europe considered dragons to be Bad Creatures. And this particular dragon is especially bad. I was much struck by the detail that its breath was so poisonous that it killed people. It strongly reminded me of a boss I once had who had dreadful halitosis; it was dangerous to get too close. He was also quite reptilian in many other ways; I was very relieved when I got another job and left.

This typing by Europeans of dragons as bad has remained unchanged up to the present. The one big addition to their badness is that the pestilential breath became a fiery breath. In that iconic set of books about Harry Potter, for instance, dragons appear several times, and of course they are dangerous, fire-breathing creatures. Dragons grace the cover of at least one of the books.

So, irredeemably bad. Mad and bad.

By one of those acts of serendipity that make the world so interesting, while we were watching St. George skewer his dragon in Genova’s Palazzo Reale, up the hill from there – a mere 15 minutes’ walk away – the Museo delle Culture del Mondo was holding an exhibition on Chinese dragons. Here’s a couple of dragons on show there.

And here are a couple of dragons amongst our possessions.

A vase my wife picked up in Suzhou during our years in China,

And a cushion cover made with a piece of fabric she picked up on last year’s trip to Kyoto.

Although Chinese dragons are fearsome-looking, the Chinese consider them to be Nice Creatures. They believe they bring prosperity and good luck. In earlier times, they were also believed to bring rain and were prayed to during droughts. Here are a couple of dragons from a Song dynasty scroll flying through mist and clouds, an early form of cloud seeding as it were.

Dragons were considered such Nice Creatures in China that the emperors adopted them as their own. Already 2,000 years ago, during the Han dynasty, the emperors claimed to be sons of dragons. By the time the Ming dynasty rolled around in 1368, the dragon, specifically the five-clawed variety, was strictly reserved for the clothes and accoutrements of the emperor and his family. Anyone who transgressed this rule risked death (along with their whole family). We have here the Emperor Ming Yingzhong wearing his dragon robe.

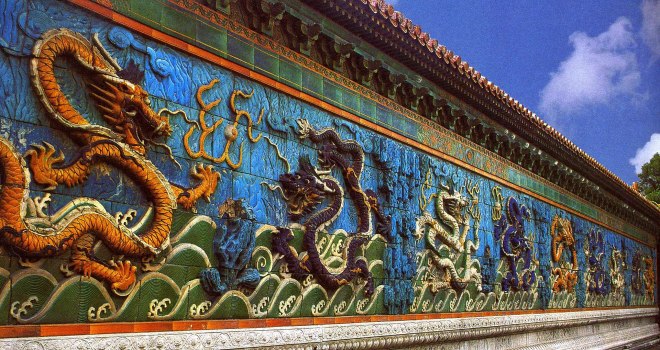

And of course the Forbidden City in Beijing, the centre of later emperors’ power, is littered with dragons. I show here two examples, the first in the Nine Dragon Wall, the second a dragon statue standing guard before one of the temples.

The Emperors graciously allowed their nobles to avail themselves of the lesser four-clawed dragon for their clothes and furnishings, while commoners were allowed to use the vulgar three-clawed dragon (I only notice now that we are guilty of terrible lèse-majesté with our vase, where the dragon in question has five claws, while our cushion cover is within the norm for commoners like us since the dragons have three claws).

So, nice and simpatico, but also very noble, these Chinese dragons.

Well, this is a conundrum! Mad and bad, or nice and noble? Who is right, East or West? Let’s put aside the obvious response, which is that since dragons don’t actually exist the question is irrelevant. That’s just party-pooping. Let’s also ignore the response that it’s all in the wings: European dragons have wings, which makes them bad, while Chinese dragons do not, which make them nice. That’s just silly; wings can’t make such a difference. How about being Solomonic and saying that dragons can actually be both, just like us, depending on which side of the bed they get out of in the morning.