Vienna, 23 September 2018

My wife and I have spent much of the summer crisscrossing the Wiener Wald, that mantle of woods draped over the hills to the north and west of Vienna, sampling the myriad paths that meander through the cool green of its beech and oak trees.

But one place I’ve tended to avoid if at all possible in our wanderings is Kahlenberg. For those of my readers who are not familiar with Vienna, this is a spot on the northern ridge of the hills where you get a magnificent view over Vienna.

But precisely because of that, and because it is easy to access by car, Kahlenberg is often very crowded with urbanites who can’t be assed to walk (here speaks the militant walker) as well as with tourists brought there by the busload to gawp at the view. If that weren’t enough, the place is imbued with a rather nasty form of nationalism, due to its role in the Battle of Vienna, fought on 12 September 1683. In this battle, a combined force of Austrians, Germans and Poles, under the overall command of Jan III Sobieski, King of Poland, comprehensively trounced the Ottoman army which was besieging Vienna. In these days of anti-Islamic feeling in Europe, the place has become a magnet for far-right groups extolling the virtues of a Europe in which Islam pointedly does not have a place. Here, for instance, is a picture of a march by a group calling itself the Identitarian Movement, which took place last year on Kahlenberg a few days before the battle’s anniversary date.

Given the role which the Poles played in the battle, and the fact that Sobieski, a national hero in Poland, had overall command, Kahlenberg is also the setting for a specifically Polish form of nationalism. The Polishness of the place was given a big boost in 1983, when on the 300th anniversary of the battle the Polish Pope John Paul II met there with what were then exiles from Communist Poland. In that same year, a plaque was unveiled on the side of the church at Kahlenberg to commemorate Sobieski. Although modest in size and design, the plaque contains inflammatory words: “To the commander-in-chief of the allied army on the 300th anniversary of the relief of Vienna for the salvation of Christendom, his grateful compatriots with the congregation of the Resurrectionists” [the latter own the church]. Salvation of Christendom … big words!

It seems that this was not enough, so at the instigation of the Poles the Vienna Municipal Council decided some years ago that a more glorious monument to Sobieski should be placed on Kahlenberg. The monument, designed and executed by a Polish sculptor, would have looked like this.

It was meant to have been unveiled this September on the anniversary of the battle. Luckily, cooler heads prevailed and the project was cancelled at the last minute, leaving just the base. But of course this led to much gnashing of teeth in the far-right media, especially the electronic media. In this time of European history, I must say that I find this xenophobic nationalism, which we see everywhere in Europe but is the official government line in Poland, really distasteful.

So, for all these reasons, I have, as I said, been avoiding Kahlenberg on our walks. Nevertheless, it just so happened that we were walking through it on 11 September, on a walk towards Klosterneuberg. When I noticed that we there the day before the battle’s anniversary date, I began to be intrigued by this battle, about which, it must be said, I knew very little, other than its outcome and what seemed to me the strange claim that the relief forces came down from Kahlenberg to give battle. I say strange because what has always struck me at Kahlenberg is how steep the drop is down towards Vienna and how far the old city seems to be. I simply could not imagine troops careering down the hill and catching the Ottoman troops unawares. There was nothing for it, I decided; I was going to have to do some reading. Now, after a few weeks of desultory consultation of whatever I could find online. I am ready to report back (in passing, I should note that I am particularly indebted to Ludwig H. Dyck’s article on the topic which I suggest battle buffs read if they want to know more).

Vienna had been under siege since July, and by September the situation was looking increasingly desperate for the defenders. This painting gives a rather fanciful view of the besieging forces, with Vienna in the distance. Readers will note some camels in the foreground.

Readers should also note two other things in this picture: the hills to the left, and the small river passing to the right of Vienna, the Vienna River. These will play an important role in the upcoming drama.

Luckily for Vienna, help was on the way. On 6th September, the Polish forces under Sobieski crossed the Danube at Tulln, some 35 km upstream of Vienna, and linked up with the Austrian and German contingents. To give readers an idea of the multinationalism of this army, the Austrians, naturally enough, made up the largest contingent, with 20,000 men, under the command of Duke Charles V of Lorraine. The Poles came a close second, with 18,000 men, the great majority of whom were cavalry. Then came troops from a number of the German states: 11,000 Bavarians, under the command of their Elector Max Emanuel, 9,000 Saxons, under the command of their Elector John George III, and finally 8,000 Franconians and Swabians, under the command of Prince George Friedrich von Waldeck. With a sprinkling of other troops from here and there, the relief force was composed of close to 70,000 men. What I want to emphasize here is that the Poles were by no means in the majority on the battlefield despite their modern proclamations that it was they who saved Vienna.

The army commanders’ first order of business was deciding who should have overall command. With all these aristocratic primadonnas around, one could imagine that reaching agreement on this would have been an almost impossible task. But the Duke of Lorraine managed, through tact, diplomacy, and a certain amount of abnegation (he was well qualified to do the job himself and he was commanding the Austrians, after all), to get everyone to agree to Sobieski being given overall command. Being a King, he could pull rank on everyone else, he had charisma, and he had beaten the Ottomans in battle ten years earlier. I throw in here a Polish painting of Sobieski, which I would say falls into the realm of propaganda, painted in the days when Poland no longer existed and Poles dreamed of having a country once more.

In truth, Sobieski was well past his physical prime by this time; he was so fat that he couldn’t get into his saddle without help. But luckily his mind was still sharp. This painting from an earlier era probably gives a more faithful rendering of what he looked like, although I doubt his horses did much prancing.

In order to soothe any ruffled aristocratic feathers, it was agreed that each Prince, Elector and Duke would nevertheless lead their own men while respecting the overall battle plan. A potential recipe for disaster, I would have thought, but one which in the circumstances actually worked.

Where was the Austrian Emperor Leopold I, readers might wonder? Should he not have been leading the army on its way to relieve his capital?

Well, at the first sign of danger he had scarpered from Vienna, along with his whole court, to the safety of Passau far in the west of Austria and a long way from the Ottoman forces. Which was probably just as well, because he was a useless soldier and had an aptitude for quarreling with all and sundry, as we shall see. Since the Duke of Lorraine played such an important role in the planning and execution of the upcoming battle, I feel it is only fair to also throw in a picture of him.

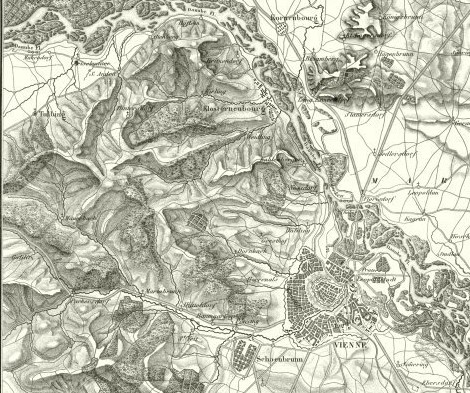

Now that the issue of command structure had been sorted out, agreement was needed on the plan of battle. The Duke of Lorraine had come up with a plan, which can be understood from this old map below.

Lorraine’s idea was to have the relief force appear on the ridge of hills to the north of Vienna (to the right of this map) and give battle on the plain below, forcing the Ottomans to have at their back the Vienna River (that rather weedy stream passing to the south (left) of Vienna), the city of Vienna itself, and the Danube beyond that: caught in a vice, as it were. It was a good plan, and in the end all agreed to it. But it carried a big risk. As this next map shows, the roads from Tulln (just off to the left of this map) to Vienna all pass through the hilly country that lies to the north-west of Vienna.

This meant that the army, all 70,000, plus all the horses of the cavalry as well as the lumbering cannons of the artillery and the baggage trains, had to cross heavily wooded, steeply hilly country intersected by numerous gullies and stream beds, along roads that were probably little more than forest roads. During walks which my wife and I have done behind Kahlenberg over the last week or so, after I had mugged up on the battle a little, I have kept marveling that the relief force had made it through this rough and rugged terrain. Here are some photos which might help readers appreciate its ruggedness.

I don’t want to pass for an armchair general but I also find it incredible that the commander of the Ottoman forces, Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa, didn’t take any steps to block their passage. He knew the Poles had crossed the Danube at Tulln and had linked up with the Austrians and Germans (I use this as a shorthand for all those troops from the German states). His scouts would surely have told him which way the relief forces were heading. It would have been easy enough to block the few roads which they would have had to take. A few well-placed cannon would have kept the relief force at bay for a considerable time. But no, no significant moves were made on the Ottoman side to bar their passage. One book I read suggests that Ottoman commanders had no experience of laying siege to a city while having a relief force threatening their rear. Well, let’s accept that. But this inactivity on the part of the Ottomans was strange indeed and was one of the factors which cost them the battle.

In any event, the relief force did make it through, although it does seem that a fair amount of muskets, cannons, and other baggage were abandoned along the way and that a good number of stragglers only managed to rejoin their regiments a few hours before the battle started.

And so it was that on 11 September, as their troops were still struggling up the flanks of the final range of hills to reach the ridge, Sobieski and his army commanders congregated on Kahlenberg to review the battlefield below them and make final arrangements. I suppose that is why Kahlenberg is host to memorials to the battle. That, plus the fact that the first inkling which the Viennese had that help was on the way was bonfires lit on Kahlenberg by an advance party.

It would be nice to think that the assembled commanders soberly reviewed plans and calmly agreed to next steps. But actually, Sobieski got into a terrible snit because he saw that the terrain below the ridge was much rougher and steeper than he had been led to believe from the rather crappy maps he had been given. He wanted to put off the attack to have more time to get his troops in position. In the event, the other commanders persuaded him to keep to the plan of attacking the next day, although at the cost of their agreeing to transfer a certain number of German regiments to his wing to screen his cavalry as they picked their way down the hill.

So it was that on 12 September the Austro-German-Polish army gave battle. I do not plan to go into excruciating detail about what happened. A brief summary will suffice, and this map should help in general understanding.

The forces under the Duke of Lorraine kicked things off on the left wing (GLW on the map) with an attack at sunrise on the village of Nussdorf, a village which I have had cause to write about in an earlier post concerning a walk we did in the Wiener Wald. The Germans in the centre (GRW) followed suit. An eyewitness on the Ottoman side, describing the soldiers coming down from the ridge, wrote that it seemed “as if an all-consuming flood of black pitch was flowing down the hills.” An arresting simile I find. This painting of the battle, while somewhat confused, does at least show this human flood down the hills (to the left).

The Ottomans fought hard and the battle went back and forth, but by noon the Turkish right wing was destroyed. Meanwhile the Poles (PLW, PC, PRW on the map) were still struggling to get down from the ridge and out of the forest. They only got in line on the right wing by about 4 in the afternoon.

By this time,the Austro-Germans were well rested from their morning exertions and eager to advance on the centre of the Ottoman line. Specifically, they wanted to capture the Ottomans’ Holy Banner, which was flying on what is now called the Türkenschanz (and where we lived for a number of years on a street called, appropriately enough, Waldeckgasse). At more or less the same time, after a few initial cavalry skirmishes, Sobieski, his armour covered by a blue, luxurious semi-oriental garb, personally led his whole cavalry in what was one of the biggest cavalry charges in history: some 14,000 cavalrymen were involved. Here’s a modern take on what the leading line of these Polish cavalrymen looked like. Readers will note those strange wing-like attachments on the riders. They were the so-called winged hussars, and were the elite of the Polish cavalry.

The Polish cavalry charge on one side and the renewed attacks by the Austro-Germans on the other side, broke the Ottoman forces, who took to their heels. The usual cutting down of fleeing soldiers took place. There was also wanton butchery. Before fleeing, the Ottomans had massacred hundreds of their captives. In retaliation, the commander of what remained of the Vienna garrison burned alive 3,000 sick and wounded Ottoman soldiers found in the Ottoman camp.

One would think that after such a great victory, all would be sweetness and light between the victors. Not a bit of it! By happenstance, the Poles stopped their advance right in the middle of the Ottoman encampment. An orgy of looting followed, the lion’s share of which went to Sobieski himself. The other commanders didn’t object to the looting per se – that was acceptable behaviour in those days – but they were really pissed off that the Poles hadn’t given them a chance to take part in the looting. After all, as far as they were concerned they had been as responsible as the Poles for the victory, and I can’t say I disagree with that. Then on the next day, on 13 September, Sobieski decided on holding a triumphal entry into Vienna, casting himself in the role of savior of the city. We have here a take on this event by a Polish artist from the late 1890s: another romanticized view with strong propaganda overtones.

I doubt it was quite as joyous an affair, because Sobieski once more seriously pissed off all the Austrian and German grandees. They felt – quite rightly – that they had been as much saviors of Vienna as Sobieski, and should have had a strong presence in the entry into Vienna. The Austrians were also angered by what they saw as an insulting breach of protocol. In their view, it should have been Leopold I as Emperor to have headed such a triumphal entry. And the Duke of Lorraine was highly irritated that Sobieski had preferred this display of narcissism to the more sensible military objective of pursuing the demoralized Ottoman forces (to be fair, Sobieski did eventually get around to going after the Ottomans, and some two weeks later he and the Duke of Lorraine annihilated an Ottoman corps).

The next day, 14 September, Leopold I arrived back from his hiding place in Passau. He was furious when he heard about Sobieski’s triumphal entry into Vienna. He was so agitated about it that he refused to pay attention to the Duke of Lorraine’s pressing problems of how to provision the relief force. He also brushed aside the Elector of Saxony, who as a devout Protestant wanted to discuss the matter of Leopold’s treatment of Protestant Hungarians. Fed up, the Elector marched his troops back to Saxony. As Protestants, they hadn’t been treated well anyway by the other, Catholic troops.

Then, on 15 September Leopold finally got around to visiting Sobieski in his camp. The meeting did not go well. Leopold ignored the presence of Jakob, Sobieski’s son, whom Sobieski had hoped to marry off to Leopold’s daughter. Sobieski, egged on by his Francophile aristocrats (France and the Hapsburg Empire were perennially at loggerheads), took umbrage to such a degree that his relations with Leopold were strained for evermore.

So a great victory, though less because of tactical brilliance on the part of the relief force than because of stupid mistakes on the part of the Ottoman commander. I’ve already mentioned his inaction in blocking the routes through the Wiener Wald. There was also his decision to leave 15,000 crack Janissary troops in the trenches around Vienna to continue the siege. And a victory, whatever Polish propagandists might proclaim, that was due as much to the Austrian and German troops as it was to the Polish troops.

In retrospect, the battle of Vienna was the beginning of the end of the Ottoman Empire, although I doubt any observers of the time saw it that way. A great victory over the Turk for sure, the greatest since Lepanto a hundred years before. But the end of the Turk? The immediate aftermath instead showed up glaringly the fissures between Catholics and Protestants, fissures which would only really heal when most of Europe simply dechristianized last century. And contrary to what one might expect, relations between Poland and the Holy Roman Empire actually got worse rather than better, just because of the childishness of the rulers involved.

So I don’t think chest-thumping memorials on Kahlenberg are really what we need. The Municipality of Vienna have in my opinion struck the right tone by having inscribed on the pediment which was meant to hold the triumphalist monument to Sobieski the following words:

“The battle of Vienna at Kahlenberg Mountain on 12 September 1683 was the culmination and turning point of the struggle between two Empires, the Ottoman Empire striving to expand to the west, and the Hapsburg Empire forced onto the defensive. A coalition army formed to protect Cracow and Vienna, led by John III Sobieski, King of Poland, came to Vienna’s aid.

More than 50,000 men from many nations lost their lives in the battles fought to break the siege.

May this historical event be a reminder for the people of Europe to live together peacefully!”

____________________________

view of the woods: our pic

View from Kahlenberg: http://ourviewfromwien.blogspot.com/2011/05/stadtwanderweg-1.html

Far-right march on Kahlenberg: https://www.gettyimages.fr/detail/photo-d’actualit%C3%A9/some-250-members-of-the-far-right-identitarian-photo-dactualit%C3%A9/844970164#some-250-members-of-the-farright-identitarian-movement-attend-a-on-picture-id844970164

Plaque to Sobieski: https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-wien-vienna-commemorative-table-for-the-polish-king-jan-iii-sobieski-130947975.html

Planned memorial to Sobieski: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Planned_John_III_Sobieski_Monument_in_Vienna,_Kahlenberg_01.jpg

Siege of Vienna: https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/the-1683-battle-of-vienna-islam-at-viennas-gates/

Jan III Sobieski on his horse: https://ludwigheinrichdyck.wordpress.com/2016/03/26/the-1683-battle-of-vienna-islam-at-viennas-gates/

Jan III Sobieski: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Philipp_Rugendas

Leopold I: https://www.giantbomb.com/leopold-i-holy-roman-emperor/3005-11949/

Charles Duke of Lorraine: http://backgroundimgfer.pw/Election-of-Stanisaw-August-Poniatowski-as-King-of-Polanddetail.html

Old map of Vienna and surroundings: https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/turkish-siege-of-vienna.html

View of the woods: our pics

Battle plan: https://ludwigheinrichdyck.wordpress.com/2016/03/26/the-1683-battle-of-vienna-islam-at-viennas-gates/

Battle of Vienna: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Vienna

Polish cavalry charge: https://about-history.com/the-battle-of-vienna-1683-and-europes-counter-attack/

Sobieski entering Vienna: https://culture.pl/en/artist/juliusz-kossak