Milan, 17 January 2020

My wife and I have recently come back from a quick trip to Geneva. The official purpose of the trip was for me to film a short video as an introduction to an online course on Green Industrial Policy, which a UN Agency is putting together. It was an interesting experience, but not what I want to write about here.

We decided to use the occasion to stay on a few days and visit Geneva, which we had last visited some 20 years ago – and very rapidly at that. For instance, we hadn’t visited any of the city’s museums. We decided to make good on this lacuna and visit two museums. One was the Museum of Far Eastern Art created by the Fondation Baur, which has an acclaimed collection of Chinese and Japanese ceramics (as I have written in previous posts, I have a particular fondness for Chinese ceramics). The other was the Museum of Art and History, which contains among other things the city of Geneva’s art collection. It is this collection which I want to write about in this post.

I don’t want to get readers’ hopes up. This collection doesn’t hold a candle to, say, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. But it is a very worthy collection: to use the Michelin Guide’s terminology, it doesn’t merit a trip (3 stars), but it is worth the detour if you are already in the area (2 stars). I propose to highlight one painting and two artists who caught my fancy.

The painting, in the first room dedicated to Medieval and Early Renaissance paintings, is “The Miraculous Draft of Fishes”, painted by Konrad Witz in 1444. Witz was German-born but was active mainly in Basel (and must have visited Geneva, as we shall see). His painting recounts a story from the Gospel of John. Jesus, resurrected, appears to seven of his disciples who have gone fishing on Lake Galilee. They have been fishing all night and caught nothing. He tells them to put down their nets once more, which they do, and immediately they haul in a large catch. They recognize him, and Peter in his enthusiasm to reach him throws himself into the water and swims over to him.

What attracts me about this painting is the way Witz has transposed the scene to a lake in Switzerland, probably Lake Geneva itself (the painting was part of an altarpiece Witz made for the Cathedral of Geneva). The buildings, the landscape, the weather, all have a distinctly Swiss feel to them. I always find it very satisfying when artists transpose stories from the New Testament to the living conditions of the people who would have been looking at their works: “bring religion to the people” as it were. It’s what I like about Neapolitan nativities. It’s what I liked about the sculpted pulpit – also about fishermen on Lake Galilee – which I came across in Traunkirchen last summer.

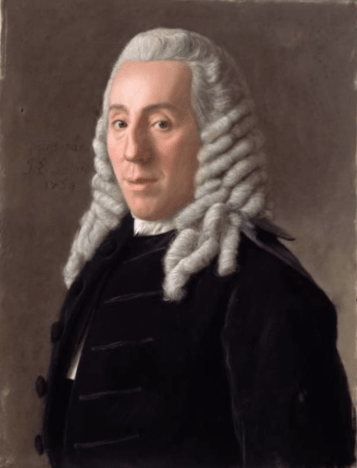

Of the two artists I will highlight, I came across the first in the room devoted to Rococo art. This artist goes by the name of Jean-Étienne Liotard. He was Swiss; in fact, he was Genevan, having been born and died there, and done much of his work there. Liotard was primarily a portraitist. As this self-portrait shows, he must have been a very merry fellow.

He seemed to have made merriness his calling card. He painted many of his clients with a small smile, like this no doubt otherwise very serious personage.

There’s a whole wall in the museum devoted to his portraits and they all have this small smile playing on their lips. I can imagine Liotard starting his sittings by cracking jokes until his subjects, who had no doubt struck a serious pose suitable to their important position in society, began giggling. Only then would he capture their physiognomy for posterity. His sittings must have been fun. Way to go, J-E!

I came across the second artist in the section devoted to 19th Century art. In fact, the museum has a whole room just for him. His name is Ferdinand Hodler, a Swiss painter who was active for some 45 years until his death in 1918. He was one of the important influences on German Expressionists and Austrian Secessionists. I had first come across him in “The Art Book”, someone’s compilation in the 1990s of “500 great painters and sculptors from medieval to modern times” (both Witz and Liotard made the cut, I have just noticed). The editor included one painting for each of the 500. The one chosen for Hodler is his “Lake Thun with Symmetrical Reflections”, of 1905.

I just loved his use of colour and light in this landscape, so uplifting of the spirits! I made a mental note to see more of him one day. Well, now I had my chance: a whole roomful of his paintings! I share some of them with my readers.

“The Eiger, the Monch, and the Jungfrau”, of 1908

“The Jungfrau seen from Murren”, of 1914

“Lake Geneva seen from Chexbres”, of 1904

“Lake Geneva and the Mont Blanc with Swans”, of 1918

Not a landscape exactly, but an element of landscape: “Stream at Champery”, of 1916

Yet another element of landscape, “The Cherry Tree”, of 1915

I should point out that Hodler has a large body of work to his name, only part of which I find appealing. As the dates I give above indicate, this phase runs from about 1904 to his death in 1918. He was also painting in the Symbolist style during this period, and the Museum has some of these works, but I’m not really touched by that type of painting.

Since I threw in a self-portrait of Liotard, let me finish with one of Hodler, painted in 1916, two years before he died.

More melancholic than Liotard, but then he had more to be melancholic about. He had lost the woman he loved to cancer and was unwell himself.

Well, that’s it for Geneva’s Museum of Art and History. As I said, 2 stars not 3, but with some 3-star highlights, particularly the room dedicated to Hodler. Researching this post, I discovered that the Art Museum in Zurich also has a good collection of Hodler’s works. We’ve never visited Zurich. I wonder if I can persuade my wife to go there one of these days …