Vienna, 24 September 2025

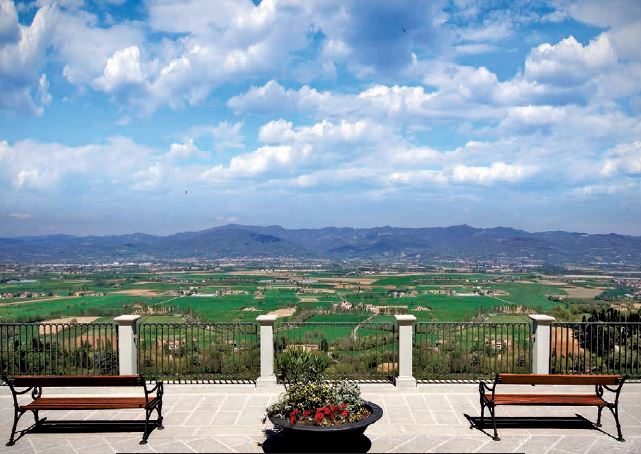

My wife and I have just finished a long weekend in the little town of Waidhofen an der Ybbs. We were actually using it as a base from which to carry out a number of very pleasant hikes over the surrounding hills. These are impossibly beautiful: broad swathes of light and dark green draped over the hills, dotted here and there with farmsteads.

The weather was glorious, which certainly helped.

As I looked through the various brochures which we picked up to figure out what hikes to do, I came across the following brief write-up about the church in a village some 10 km away, the village of St. Leonhard am Walde:

“Fiakerkirche St. Leonhard/Wald: The traditional place of pilgrimage for Viennese hackney carriage drivers since 1826. St. Leonhard is the patron saint of cattle, sheep – and horses. In 1908, the Viennese hackney carriage drivers donated the Marian altar. A few decades ago, the Viennese cab drivers also joined the pilgrimage.”

Now that really intrigued me! Hackney carriages, fiaker in German, are a picturesque sight down in the centre of Vienna, although nowadays, of course, they are only for tourists.

But, being an early form of taxi, there was a time when hackney carriages were ubiquitous throughout the city, as indeed they were in all European cities. Here is a colourised copperplate engraving from the 1830s of a smart set of Viennese and their carriages.

I suspect, though, the carriages and their drivers didn’t look quite so smart when they were merely acting as taxis, ferrying people around town. This looks more like the typical hackney carriage driver; the photo is taken from an engraving in a book of 1844.

Hackney carriage drivers have always struck me as a hard-boiled lot, not taken to making pilgrimages. I have a hard time seeing them doing this (this is a modern pilgrimage, but I don’t suppose pilgrimages have changed much, apart from the clothes the pilgrims wear).

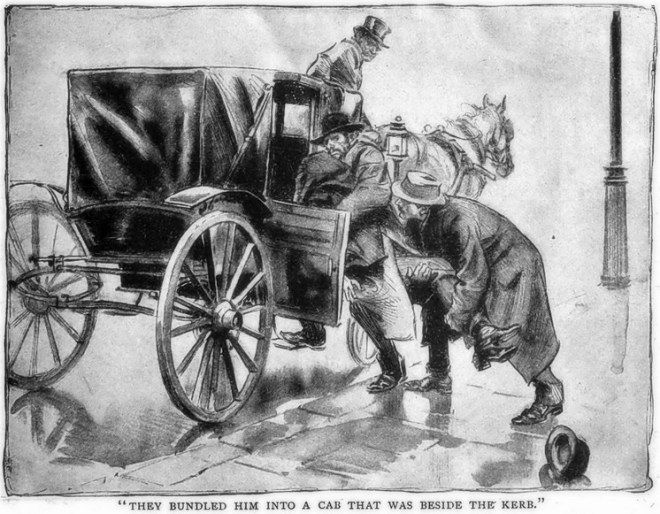

But it could be that I am being influenced by various books I’ve read and films I’ve seen where hackney carriage drivers seemed to be a sinister and semi-criminal lot. This is an example from one of the Sherlock Holmes stories.

Maybe the majority were God-fearing, devout, family men.

Of course, given the way my mind works, I started wondering why hackney carriage drivers would have chosen a church dedicated to St. Leonard as the church to which they would make their annual pilgrimage. The little blurb I quoted above suggests an answer: he was the patron saint of horses, and of course horses were key to hackney carriages, being their motor as it were. But how, my mind was asking, did Saint Leonard become the patron saint of horses?

Since I knew nothing about Saint Leonard, I had to do some reading. I should note in passing that there have been various Saint Leonards over the centuries; the one we are interested in is St. Leonard of Noblac. Assuming he ever actually existed, his story is quickly told.

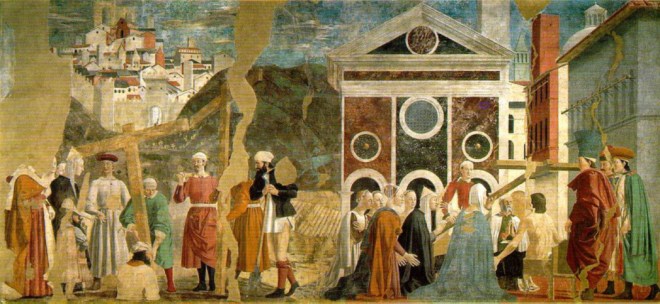

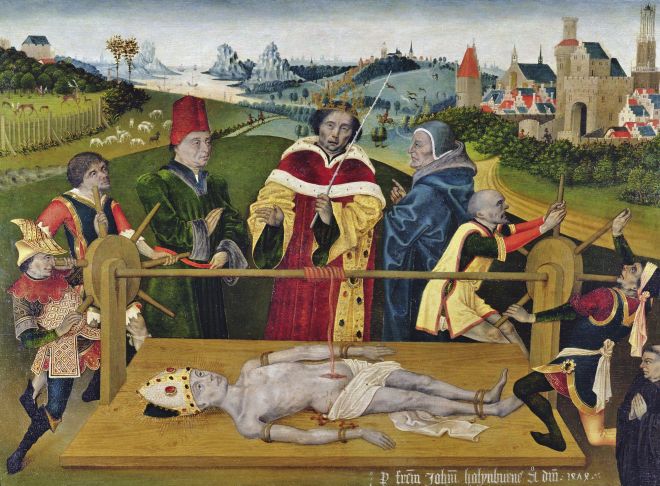

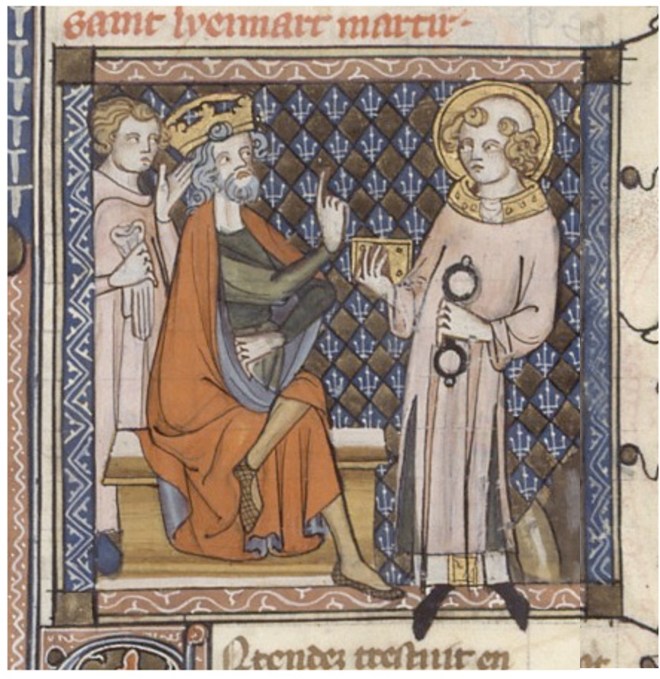

Leonard was a Frankish nobleman, coming from a family that was closely allied to Clovis, the first Frankish king of what was later to become France. Clovis was young Leonard’s godfather when he was baptised, along with Clovis himself and all his court, by St. Remi, bishop of Reims, on Christmas Eve of 496. As Leonard grew up, he became much exercised by prisoners, to the point where he asked Clovis to have the right to visit prisoners and free those he considered worthy of it. Clovis granted the request. We have the scene played out here in a French work from the 14th Century.

Many prisoners were thereafter liberated by Leonard.

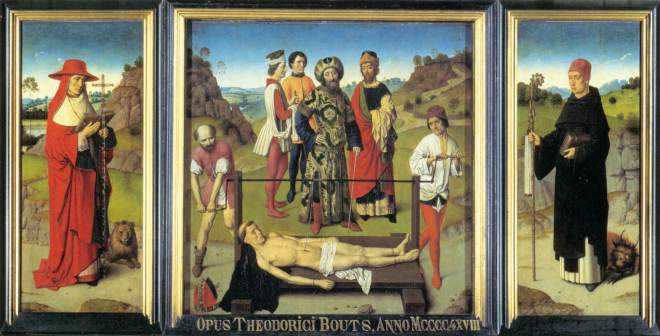

Much impressed, I presume, by his holiness, Clovis offered him a bishopric, but Leonard turned the honour down, preferring to join a monastery near Orléans, whose abbot was another saint, St. Mesmin. After the latter went the way of all flesh, Leonard decided to strike out on his own. He moved to a forest in a place called Noblac (Noblat today) near Limoges, where he set up a hermitage. His preaching, good works, etc. led to a multitude of people flocking to his hermitage, including many prisoners whose chains miraculously flew off their hands and legs after they had prayed to St. Leonard for his intercession. Here, we have a print from 1600 giving us a rather fanciful vision of this scene.

I do believe that the monk working the land behind Leonard in the print is one of these prisoners now living an honest life.

At some point in all of this, the-then Frankish king Clotaire I (Clovis having died in the meantime) and his heavily pregnant wife came to visit Leonard in his forest hermitage – we have to remember that Clovis’s family and Leonard’s family were close. The royal couple decided – like the good aristos that they were – to use the occasion to go for a hunt in the forest. To get us into the spirit of things, I throw in here a miniature from the 15th-Century Book of Hours of Marguerite d’Orleans showing Lords and Ladies off to the hunt.

During the hunt, however, the queen suddenly went into labour. It was turning into a difficult and dangerous birth. Leonard rushed to her side and his prayers saved queen and baby. In gratitude – especially since it was a baby boy – the king wanted to shower Leonard with loads of money. But Leonard only asked for as much forest area around his hermitage as he could ride around on his donkey in one night. The king granted this wish. On the land that Leonard was subsequently given he built a church and monastery. He became its first abbot and died there peacefully, mourned by all. The Romanesque version of that church still stands, in a place called Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat.

And that church contains what is purported to be Saint Leonard’s tomb.

Given his involvement with prisoners, it is not surprising to learn that St. Leonard is the patron saint of prisoners. Given that story with the pregnant queen, it’s also not surprising that he is considered a helper of women in childbirth. But patron saint of cattle, sheep and horses? How did that come about?

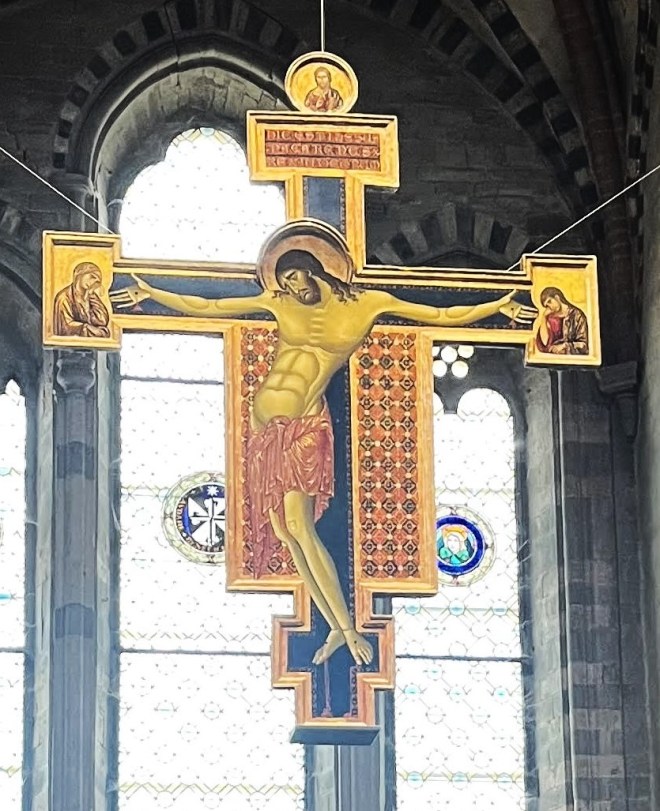

For that, we have to know that from the earliest times St. Leonard was often depicted as an abbot with a crosier and holding a chain or fetters or manacles, symbolising the liberation of prisoners achieved by him. In fact, in one of those serendipitous moments I love so much, I came across just such a representation of him in a church in Waidhofen, down the road from where my wife and I were staying.

Over time, rural folk mistakenly thought that the chains which St. Leonard was holding were cattle chains – these are commonly used to tether cattle or to control them during walks, or even to help birthing calves.

By extension he became the patron saint of all farm animals, which of course also included horses.

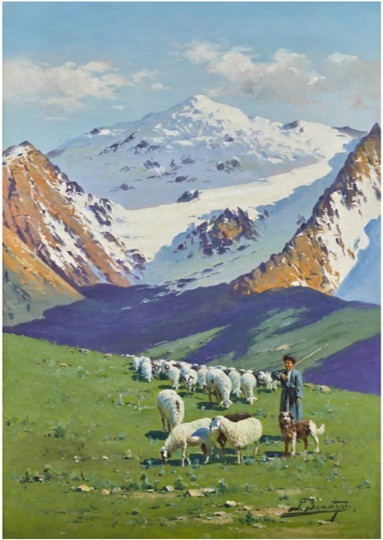

Given this swerve of patronage towards livestock, I suppose it’s not surprising that Saint Leonard became a popular saint throughout the Alpine regions of Europe. After all, as I’ve mentioned in a previous post, cattle was pretty central to the rural economies of all Alpine communities. This devotion to the saint means that his feast day – November 6th – is celebrated with enthusiasm in many places in the Alpine regions, especially the German-speaking ones. Here, for example, are photos of the celebrations in Bad Tölz in Bavaria (which got a mention in an earlier post because of its rather naughty statue of St. Florian).

It also gave rise to the intriguing phenomenon of chain churches in the Alpine regions. These are churches dedicated to St. Leonard which have chains running around them, either put up temporarily on his feast day or mounted permanently. The Fiakerkirche is not a chain church, alas. Here is a nice example from Tholbath in Bavaria (the church also has a quite respectable onion dome, the subject of an earlier post).

But if we’re going to visit a church dedicated to St. Leonard, it won’t be one of the chain churches. It will be the one I’ve already mentioned in Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat. What a fine-looking Romanesque church! I have to say, I am partial to Romanesque churches. I’ve already inserted a photo of the church’s exterior. Here is a photo of its interior.

What a wonderfully bare church! No annoying accretions to cover the spare, simple lines of the architecture.

But the photo shows an additional reason why I will try to persuade my wife to travel all the way to France to see this church: the rucksacks and the walking sticks. This church is situated on one of the four Ways of St. James of Compostela through France. I’ve mentioned one of these, the Via Tolosana, in an earlier post. The church of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat is on another, the Via Lemovicensis, the Way of Limoges. There must surely be some good hiking to be done in the area.