Vienna, 29 August 2024

updated Sori, 10 March 2025

My wife and I were walking along some street a few weeks ago when I spotted a gorgeous red FIAT 500 driving past. Of course, I didn’t have the gumption to take a photo, so this one which I’ve lifted from the web will have to do.

I have a doubt, though. Was it a FIAT 500, or was it a FIAT 600? I must confess to never having been able to distinguish very well between the two. So just in case, I also throw in a photo of a red 600.

Just to help readers understand why I get confused between the two, I throw in a composite photo of a FIAT 500 and FIAT 600 nose-to-nose.

I think readers will agree that they really are very similar, with the 600 being slightly longer to allow passengers to (more or less) sit comfortably in the back seat.

I’ve always had a fondness for quirky little cars. The VW Beetle comes to mind.

So does the Citroën’s Deux-Chevaux (2CV).

My childish side moves me to also include here a photo of two of the deux-chevaux’s equally quirky drivers, Dupont and Dupond from Tintin.

My excuse for doing so is that my mother had as friends two old ladies who were twins, and they would always come and visit us in a deux-chevaux. While they didn’t drive quite as badly as Dupont and Dupond, their arrival was always accompanied by a mini-drama when they were parking.

I think I can go so far as to add the Morris Mini-Minor to the list of quirky cars, although, while having a fairly high quirkiness coefficient, it is not, in my humble opinion, as quirky as the other cars I’ve mentioned.

That being said, it did have a pretty cool part to play in the original 1969 film “The Italian Job”, with Michael Caine.

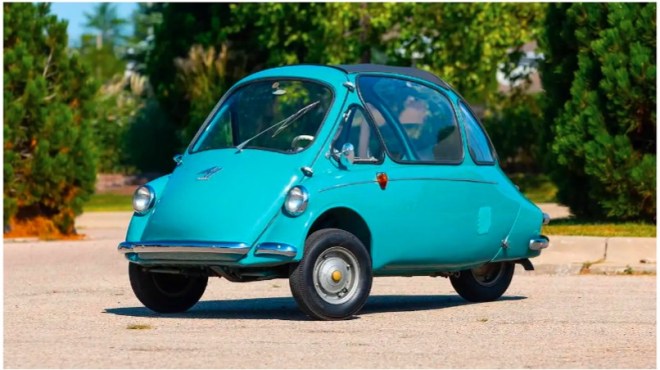

In my youth, I would also see bubble cars like this one.

In my opinion, though, they’re not quirky, they’re just weird, like Trump.

I might be fond of quirky cars, but I’ve never actually owned one. The closest I’ve ever been to quirky-car ownership is through my wife, when she co-owned a white FIAT 600 with her flatmate while doing her graduate studies in Bologna. It must have been twenty-fifth hand, that car. We took it on a long road trip over a Christmas holiday to Puglia. My mother-in-law accompanied us; the saintly woman spent the whole trip wedged in the back. Being rather old, the car had a problem of leakage from the radiator. Every 100 km or so, we had to stop and top up the water. At these moments, my mother-in-law would ask out loud if we would ever make it to our destination. To capture a little of that drive to Puglia, I throw in a photo of a FIAT 600 rockin’ down the highway, as the Doobie Brothers sang way back in 1972.

That one trip is the only time I’ve ever driven one of these quirky cars. I once accompanied a University flat mate of mine on a long, long trip from London to her mother’s place in Austria (I mentioned this trip in my last post). She was driving a Dyane, not quite as quirky as the original deux-chevaux but close enough.

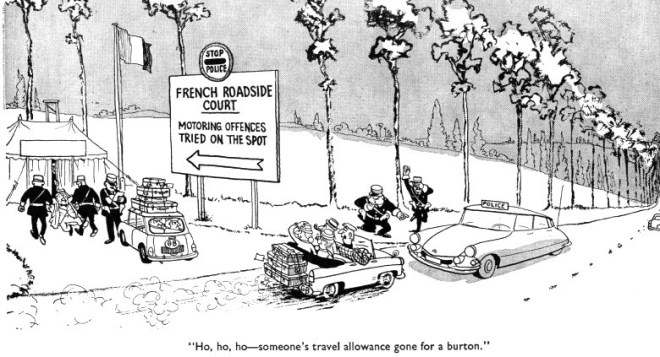

I didn’t drive because I didn’t have my license yet (I’m not sure she would have let me drive anyway; she was very possessive of her Dyane). Apart from the length of the trip, the only notable thing that happened is that a Frenchman wearing a beret (I kid you not) drove into my side of the Dyane about half an hour after we had left Dunkirk. Classic British-French misunderstanding. My friend thought she had priority because she was on a large main road and the bereted Frenchman was coming in from a small road on the right. He, on the other hand, was strictly applying that quirky French rule of the road “Priorité à droite”, regardless of relative road sizes.

At least my friend wasn’t driving on the left-hand side of the road … This is a cartoon from way back in 1966 by the famous British cartoonist Giles.

In contrast, a FIAT 500 (or maybe FIAT 600) was part of a scene of Italian-British cultural exchange earlier in my life. The one and only cruise I’ve ever been on (it is the subject of an an earlier post) stopped off in Brindisi on the way back to Venice. It was 1968 or ’69. A group of us youngsters on the ship went for a stroll through town. We were of course noticed by the local population, especially since one of us was a very pretty blue-eyed, blonde-haired teenager. Within minutes of us beginning our walk, this white 500 (or maybe 600) came careening around the corner on two wheels and came screeching to a halt next to us. The car’s driver and passengers all hopped out and after much hand waving and some words we managed to understand that they were inviting us to a café for a drink. Since none of us spoke Italian and none of them spoke English, the conversation was exceedingly limited. Nevertheless, a good time was had by all. Eventually, we went our separate ways, they in the 500 (or 600?), which careened away around the corner on two wheels. To celebrate this moment of entente cordiale in Italy, I throw in a photo of a bar in Brindisi from perhaps 10 years earlier, with what definitely looks like a FIAT 600 parked outside it.

These quirky cars are of course collectibles now. One fellow who I worked with – the one who once spent more time getting local salted capers than doing the work, as I’ve mentioned in an earlier post – recounted to me in excruciating detail his efforts to do up an old 500 he had bought. Maybe it looked something like this when he bought it; this particular FIAT 500 has been quietly mouldering away for at least ten years now in a parking space down the road from our apartment at the seaside.

He told me that all he needed to find was the original of one small part (some sort of knob) and he was done. The car would be worth millions! (of liras) I never did find out if he managed to lay his hands on that small part …

Of course, it comes with my age to say that they don’t make things the way they used to anymore. But in the case of quirky cars, it’s really true. Modern cars are so boring, no character, just boxes on wheels. Even the modern cars whose manufacturers exploit the mythic status of the old quirky cars by giving them the same name are but pale imitations of the originals – if they look like the original at all.

The new FIAT 500 EV looks quite like the old 500, just pumped up, as if it has been attending a body-builders’ gym.

The new FIAT 600, on the other hand, bears absolutely no resemblance to the old FIAT 600.

For its part, the new Mini Cooper looks a teeny-weeny bit like the old Mini-Minor.

As for the deux-chevaux and the Volkswagen beetle, no-one has (yet) dared come out with a modern imitation of them.

The only exception I would make to my damning judgement of modern cars is the Smart Fortwo car.

Now that is a car with character! You can see in the photo one of its quirky characteristics, that it can be parked head onto the pavement.

My wife and I once stayed at a hotel which offered a free drive in a Smart. No idea why, but we said “what the hell, why not?” and we took it for a spin. A most delightful experience! If I had to own a car, which I most definitely do not, I would try to persuade my wife to buy a Smart. Actually, instead of buying why not join a car sharing scheme? Car2go offers Smarts.

What new quirky cars might I see before I pop my clogs? Surely the new era of EVs will throw up a quirky car or two. I wait with bated breath.