Milan, 12 February 2026

A couple of weeks ago, my wife and I went on a quick three-day trip to Verona. We’d made a lightning visit there a few years ago, when we had a couple of hours to wait at the station for our train connection. I have no memory of that visit other than standing in front of a balcony purported to be the one where Juliet stood while talking to Romeo (“O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?” etc.) and wondering what on earth the fuss was about – as far as we could tell, 90% of the tourists flocking to Verona had come to see this.

This time, we were determined to keep completely away from anything related to the two “star-cross’d lovers”, and we succeeded admirably. I have to say, we were greatly aided in this by relying on an old and well-thumbed guidebook of the Touring Club Italiano, which my parents-in-law had bought way back when.

It had been published in 1958, long, long before the current instagram- and TikTok-fuelled hysteria about Romeo and Juliet, and so had not a word to say about them. For the first two days, we faithfully followed the two itineraries suggested in the guide, while we spent the third day visiting a couple of art museums.

So, “let us go and make our visit”, as T.S. Eliot intoned.

Since our Flixbus from Milan arrived at around lunchtime, we actually started proceedings by going to lunch – always good to start a visit on a full stomach! My wife had identified a trattoria that looked interesting, the Osteria A Le Petarine, at the far end of the old city. To work up an appetite, we walked up there. That took us through Porta Borsari, an ancient city gate that started life as the main gate in the city’s ancient Roman walls.

We continued up corso Porta Borsari, the old decumanus maximus of Roman Verona, and now a pleasant pedestrianised street.

After a few dog legs through the narrow streets of the old town, we finally arrived at the trattoria.

My wife was not persuaded by her choice, but I had an excellent Pastisada de caval, a dish of horse meat stew laid on a bed of polenta.

After lunch, we headed over to our hotel, dropped off our bags, and sallied forth on our first itinerary. This took us first to piazza delle Erbe, which has been the centre of Verona’s civic life since Roman times, when this was the forum.

It’s unfortunate that the square has been invaded by stalls selling tourist tat. It’s difficult to get a clear view of the square now.

The itinerary instructed us to next take a small street leading off the square, which took us to the Arche Scaligere, the tombs of the Della Scala family, which was Verona’s most famous family, ruling the city in the Middle Ages.

The itinerary then led us to Santa Anastasia, the first of four churches we were to visit. We would have visited a few more churches, but they were closed the day we tried to visit them (I think my wife was quite relieved by that; it is possible to have too much of a good thing).

Santa Anastasia’s facade, the first part of the church we saw, was nothing to write home about, and in fact I later read that it was never completed (a problem in Italy which I’ve complained about in an earlier post).

The inside was a different story: tall, airy, and with a ceiling painted with a vegetation motif. It quite put a bounce in my step to see all that exuberance on the ceiling.

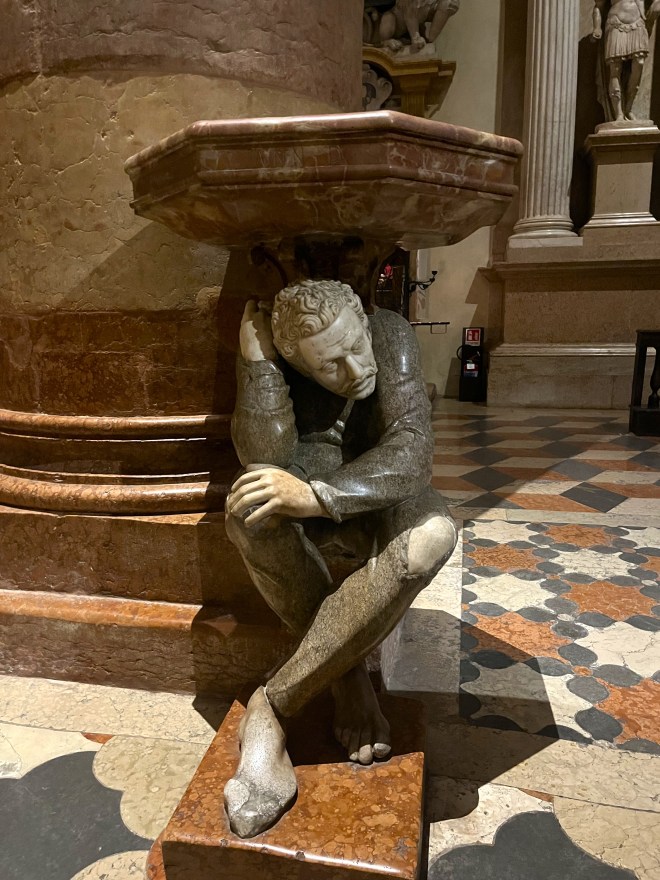

Of the internal details, there were a couple of frescoes and paintings by Worthy Artists, but the one that caught my eye was these two holy water fonts. I’ve never seen any fonts quite like these.

The itinerary next took us to the Duomo. It was early evening by now, so our visit was hampered by a lack of light. Whether it was that or simply that there wasn’t much to see in the Duomo, I have only vague memories of it. Nevertheless, I’ll throw in a few photos from the internet.

The exterior:

A view of the inside:

The one detail that caught my attention, this semicircular choir screen that encloses the presbytery:

After which, we decided to call it a day (or rather night since by now it was pitch black) for our sightseeing.

But we weren’t ready for bed yet! My wife had got us tickets to a show where a dance troupe danced to Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps.

The music was lovely, the dancing rather less so. Nevertheless, it was a very pleasant end to the day.

The next day saw us pick up the second itinerary a few streets away from our hotel. The first stop was the church of San Fermo Maggiore.

It’s actually two churches in one. The lower church is the oldest. Its low ceiling gave the space an intimate feeling.

The most interesting detail was the frescoes which decorated many of the pillars. My wife and I agreed that this 11th Century fresco, of the Baptism of Christ, was the most remarkable.

But I also liked this fresco from the same period, of the Virgin Mary breastfeeding the baby Jesus.

We also agreed that this modern sculpture, of the Annunciation, was wonderful.

The normal iconography is something along these lines: an angel – obvious because of its wings – on one side, announcing the message, and the Virgin Mary, modestly attired and sitting or standing, reading a book, on the other (I’ve chosen the Annunciation by Pinturicchio as my example).

But here you have what looks like two young women, adolescent girls almost, one, the angel, whispering the message to the other, the Virgin Mary. In case any readers are interested, it is by the South Tyrolian sculptor Hermann Josef Runggaldier.

We then climbed the stairs to the upper church. After the intimacy of the lower church, the space felt majestic.

The most remarkable aspect of this church was its wooden ceiling.

It was built in the first half of the 1300s and by some miracle it has survived until now (I think with melancholy of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, whose centuries-old forest of oak logs in its ceiling caught fire back in 2019 and nearly burned the whole cathedral down).

This funerary monument for Niccolò Brenzoni, from the early 1400s, was also arresting.

The itinerary now took us to the River Adige, which encloses the old town in a large hairpin bend.

It had us cross the river and walk along its bank. We got to admire the church of Santa Anastasia and its campanile from the back, much nicer than from the front.

We passed the old Roman bridge, much remodeled over the centuries (and partially destroyed by the Germans, who blew it up when they retreated out of Verona in 1945).

We passed the old Roman theatre which had been carved into the side of the hills running alongside the river. It has been turned into a modern outdoor theater.

But this is what it looked like to us as we walked past it, some mouldering walls with houses built on top of it.

The skyline was now dominated by the church San Giorgio in Braida, which sits next to the river.

Alas! A visit was not possible because the church was closed. No matter! We admired the view of the Duomo across the river.

And since we were beginning to feel a bit peckish, my wife used this pause to find another trattoria in the vicinity where we could have lunch. She discovered the Osteria A La Carega, located down a small road which we took just after we had recrossed the Adige.

We shared a pasta e fagioli as a first, after which I had a trippa alla Parmigiana while my wife chose a cotechino con puré. Delicious!

Nourished and refreshed, we picked up the itinerary again. It now took us to piazza Bra, a large square along one side of which stands what is probably Verona’s most well-known monument, the ancient Roman amphitheatre.

We couldn’t actually see much of the amphitheatre since workers were busily getting it ready for the closing ceremony of the Olympic Winter Games. The square itself is very pleasant, with a row of cafes along one side (mostly tourist traps, unfortunately)

And with a little garden in the middle (we see the wall of the amphitheatre on the left).

The itinerary now took us back to the river. We skirted the Castelvecchio (we would be visiting its art museum tomorrow) and admired the view of the ponte Scaligero over the River Adige, behind the castle.

As we discovered the next day at the art museum, it was a view that had been painted by Bernardo Bellotto in about 1745.

Little seems to have changed in the intervening centuries.

The itinerary drew us along the river and then through a maze of little streets to the church of San Zeno. As we entered into the piazza, this was the view that greeted us.

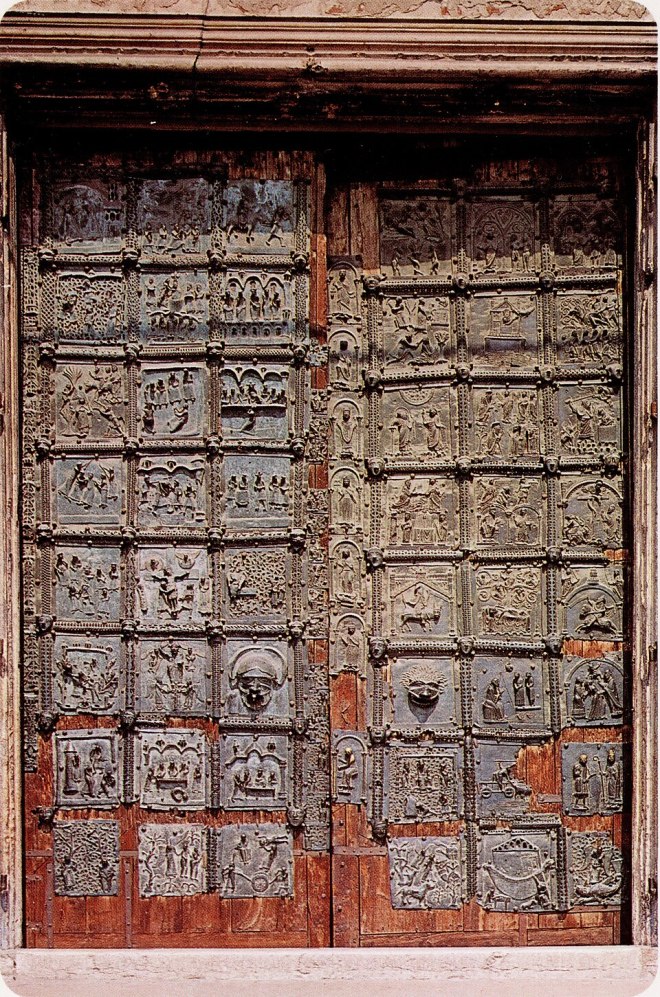

In particular, the main door was fantastic (although you only see it from inside the church). It is made up of 48 bronze tiles, produced in the 11th and 12th Centuries.

Each tile represents a story about Jesus or, more rarely, Saint Zeno. Here are close-ups of a couple of the tiles, just to whet readers’ appetite. From left to right, they represent the washing of the disciples’ feet by Jesus, and the Last Supper.

The interior was light and airy.

There was a hodgepodge of frescoes on the walls, all very pleasant.

But the fresco that really caught my eye was a giant St. Christopher.

It was nice to see this gentle giant again after my sightings of him in one of our hikes in Austria last summer. No doubt he was there to greet pilgrims from Central Europe who had come over the Brenner Pass and walked down the valley of the Adige River, on their way to Rome or Jerusalem.

Our visit to San Zeno brought us to the end of the second itinerary. We celebrated with a nice cup of tea in a bar across from the church, and then slowly made our way back to our hotel.

On our final day in Verona, we visited two museums, both dedicated to Veronese artists. We started with the museum in Castelvecchio, which was once the castle of the Della Vecchia family.

The collection goes from the Middle Ages to the 18th Century. My wife and I both agreed that the statuary from the Middle Ages was the most interesting. Here is a sample:

A most expressive St. Catherine

I’ve never seen a Medieval statue look at you in that way!

Christ on the cross

I’ve never seen such a suffering Christ!

A Sant’Anna Metterza, a formalised composition where the Virgin Mary, holding baby Jesus, sits on the lap of her mother, St. Anne.

I’ve always found this such an improbable situation: what grown woman would ever sit on the lap of her mother!? But it was a popular subject. Famously, Leonardo da Vinci painted a version.

The equestrian statue of Cangrande Della Scala, the greatest of the Della Scala family.

From the broad smile on his face, Cangrande must have been a very merry fellow.

After the visit, it was time for lunch. We chose a restaurant near Castelvecchio, but unfortunately it turned out to be a tourist trap, so I won’t bother to report on what we ate. We then walked back up to the Piazza delle Erbe; the second museum we visited, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna Achille Forti, was installed in the old Palazzo della Ragione, which gives on the square.

It covered the 19th and the first part of the 20th Centuries. To be frank, there wasn’t much in the collection that struck me. This statue, of a young woman wearing a hat typical of the 1920s, was one of the few pieces that caught my attention.

Otherwise, a couple of paintings which showed views of the city from the top of the hills above the old Roman theatre made me regret that our old guidebook hadn’t included an itinerary taking us up into those hills. Here is a view of the city from the top of those hills.

With that, our visit to Verona was over. We walked down another of the city’s very pleasant pedestrianised streets, via Mazzini, which runs from piazza delle Erbe to piazza Bra.

And then on down Corso Porta Nuova, a broad avenue running through the newer part of the city.

And so back to the bus stop to take our Flixbus back to Milan.